A newly recorded rock carving in the southwest Sinai Desert provides rare visual evidence of early Egyptian expansion into the peninsula around 3000 BCE. The scene, cut into a prominent rock face in Wadi Khamila, presents a violent encounter linked to control over mineral resources. Researchers interpret the imagery as an early statement of Egyptian political and religious authority beyond the Nile Valley.

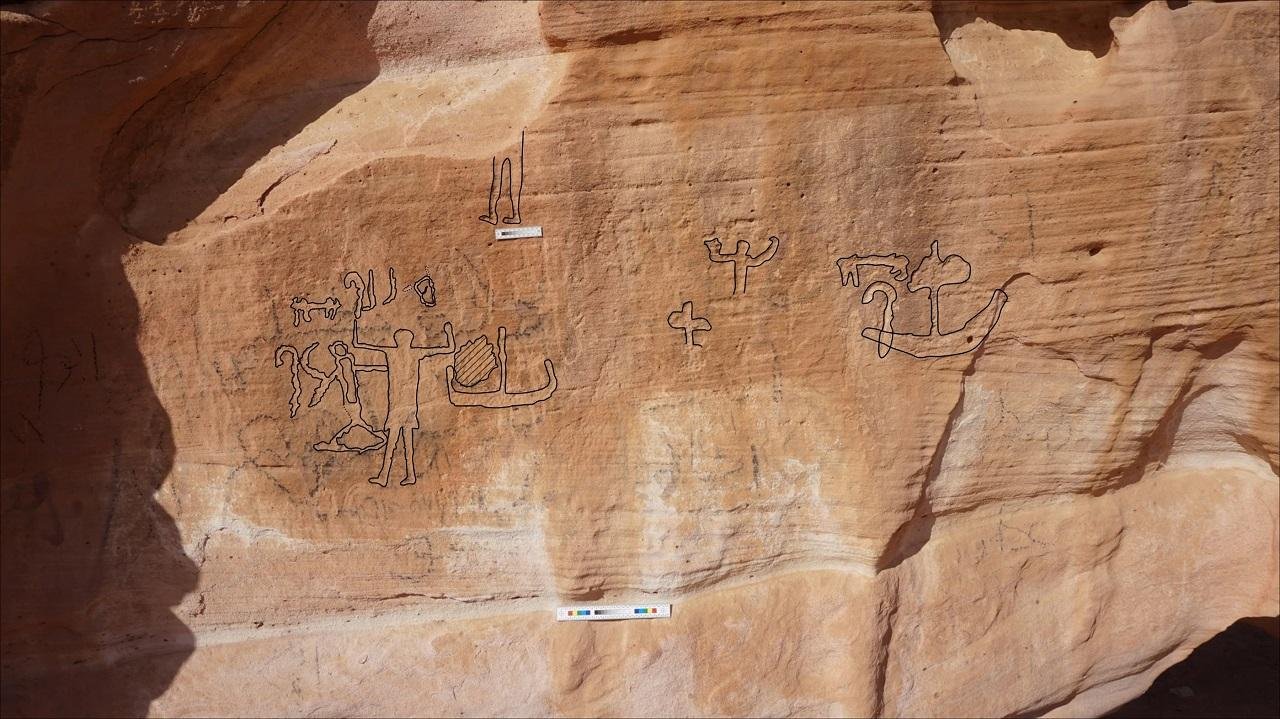

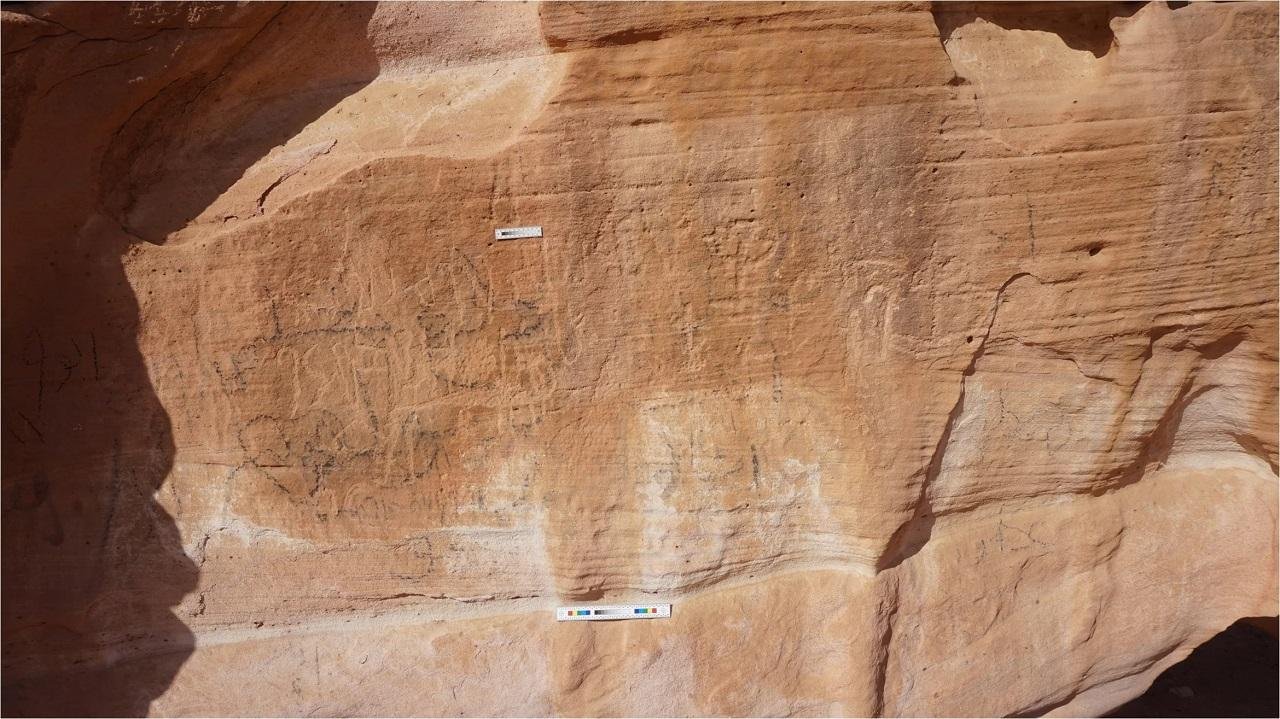

Mustafa Nour El Din of the Aswan Inspectorate at the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities documented the carving during a field survey. Egyptologist Ludwig Morenz of the University of Bonn led the study of the images and inscriptions. The panel shows a large standing figure with raised arms facing a kneeling man struck by an arrow. The wounded figure’s posture signals defeat and submission. Nearby, a boat appears carved in outline. Early Egyptian art often used boats as symbols of royal power and state presence.

Short hieroglyphic text includes the name of the god Min. In early Egyptian history, Min held strong links to desert routes and mining zones. One inscription identifies Min as ruler of the copper region. Copper and turquoise deposits in Sinai drew repeated expeditions from the Nile Valley during the late fourth millennium BCE. Archaeological evidence from other wadis in Sinai, including Wadi Maghara and Wadi Ameyra, records similar missions tied to the extraction of raw materials.

Researchers see the composition as a message placed in a visible location along a travel corridor. The standing victor likely represents Egyptian authority under divine protection. The kneeling figure represents local inhabitants. The imagery forms a narrative of domination linked to resource control. Such visual claims supported economic expansion and reinforced ideological control over distant zones.

Dating rock art in open desert remains complex. Scholars compare carving style, sign forms, and subject matter with better-dated material from Egypt. The artistic conventions on the Wadi Khamila panel align with late Predynastic and early Dynastic imagery. This period saw growing state organization and long-distance expeditions backed by royal institutions and temple cults.

One erased section near the boat suggests a royal name once stood there. Deliberate removal of rulers’ names occurred at several points in Egyptian history during political change. No clear trace identifies the original figure. Even without a preserved name, the scale and symbolism of the scene indicate official sponsorship rather than informal graffiti.

The Wadi Khamila site held little prior evidence from this early period. Earlier research focused on much later Nabataean inscriptions in the same valley. The new find extends human activity in this area back roughly three millennia earlier than previously recorded. Multiple later markings appear over parts of the ancient scene, including recent graffiti. Reuse of prominent rock surfaces occurred often in desert landscapes.

The study frames the carving as part of a broader network of Egyptian desert inscriptions marking routes, water sources, and mining districts. These markers communicated presence, authority, and divine backing to travelers and local groups. Field teams plan further surveys in nearby valleys to document additional panels and map patterns of early Egyptian movement across Sinai.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.