Researchers have identified previously unreadable texts on wooden fragments from Roman wax tablets excavated in Tongeren, Belgium, offering new evidence about administration and daily life in a northern Roman city. The study results from a collaboration between Markus Scholz of Goethe University Frankfurt and Jürgen Blänsdorf of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

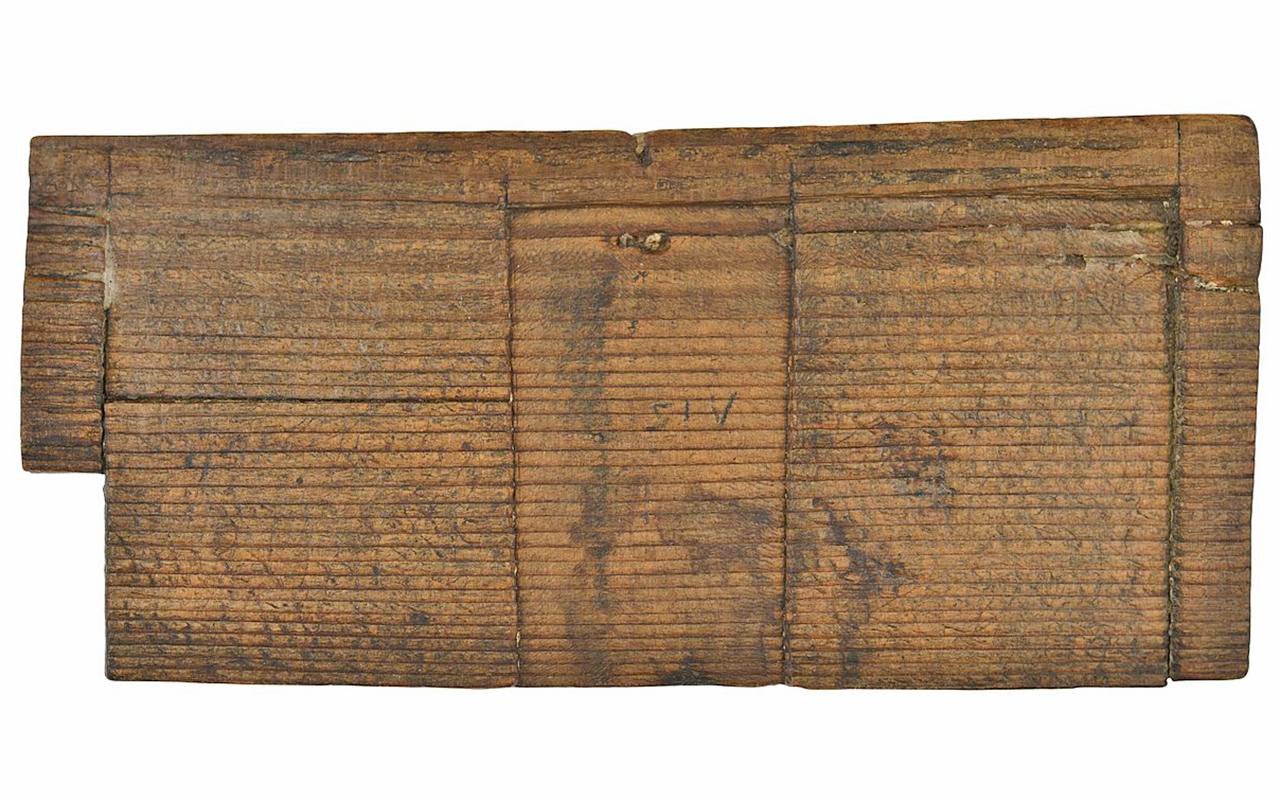

Tongeren, known in Roman times as Atuatuca Tungrorum, ranks as Belgium’s oldest city. Archaeological work since the early twentieth century has produced large quantities of Roman material. Among these finds were small wooden fragments recovered during excavations in the 1930s. Archaeologists first interpreted these pieces as parts of boards or containers. Later research showed these fragments formed the frames of wax tablets, common Roman writing tools used for contracts, official records, and education.

Wax tablets held a thin wax layer used as a writing surface. When scribes pressed a stylus into the wax, pressure often left faint impressions in the underlying wood. The wax disappeared long ago, and early scholars believed no writing survived. The fragments remained largely ignored until 2020, when Else Hartoch of the Gallo-Roman Museum in Tongeren reexamined the material and proposed further study.

Scholz and Blänsdorf began systematic analysis in 2021. The work proved difficult. The wood had dried completely, and natural grain patterns, cracks, and surface damage obscured intentional marks. Many tablets had been reused, producing overlapping traces from different texts. Advanced imaging methods, including reflectance transformation imaging, supported the work, yet repeated direct examination of the originals remained essential.

The team studied eighty five fragments from two archaeological contexts. One group came from a well near the forum and public buildings. Damage patterns suggest deliberate destruction before disposal. Such action likely aimed to prevent later reading of official information. Texts from this group include contracts and administrative documents. Scribes applied strong pressure during contract preparation, which increased the chance of survival for deeper impressions.

A second group came from a muddy pit filled with refuse used for drainage. This assemblage shows greater textual variety. Researchers identified administrative copies, writing exercises produced by learners, and a draft inscription prepared for a statue of the future emperor Caracalla, dated to CE 207. This draft offers rare insight into preparation stages for public monuments.

Only about half of the fragments preserve legible traces. Even so, the content expands knowledge of provincial administration. References appear to a decemvir, a senior magistrate, and to lictors, attendants of high officials. Such offices rarely appear in evidence from northern provinces. Personal names recorded on the tablets reflect a diverse population with Roman, Celtic, and Germanic backgrounds. Several individuals appear as former soldiers who settled locally after service, including veterans of the Rhine fleet.

The study demonstrates the value of careful epigraphic work on modest materials. These wooden fragments preserve details of legal practice, education, and social structure within a Roman frontier city, adding new depth to understanding of provincial life during the second and third centuries CE.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.