Researchers have identified a fatal bear mauling as the cause of death for a Gravettian teenager buried about 28,000 years ago in Arene Candide Cave in Liguria, Italy. The individual, long known as Il Principe due to the richness of his grave, was excavated in 1942. Early observers noted severe damage to the jaw and left shoulder, but no full forensic study followed. A new analysis of the skeleton now provides a detailed reconstruction of the violent event.

The team reexamined the remains after obtaining permission to remove bones from museum display for close inspection. They used magnification, high-resolution photography, and three-dimensional surface models to document trauma across the skeleton. Several injuries occurred around the time of death. These include massive fractures in the shoulder region and lower face, damage to teeth, and possible trauma in the neck vertebrae. The pattern points to a strong blow and crushing force to the upper body.

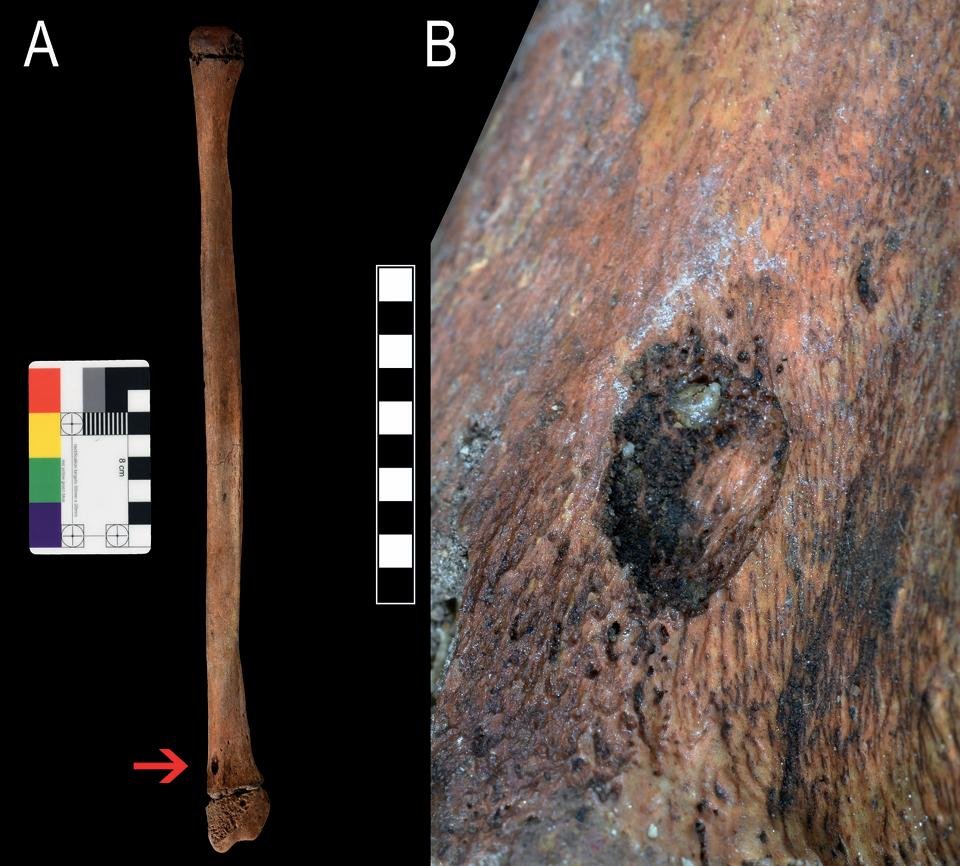

Two specific marks support the involvement of a large carnivore. A short linear groove on the left side of the skull matches the size and shape expected from a claw. A deep puncture in the lower leg bone fits the profile of a tooth from a large predator. When viewed together with the broader fracture pattern, the injuries align with a mauling rather than a fall or human conflict. Among large carnivores present in Late Pleistocene Italy, brown bear and cave bear stand as the most plausible attackers.

Microscopic study of bone tissue revealed early stages of healing. Researchers observed intertrabecular bone formation but no advanced callus growth. This stage of repair indicates survival for a brief period after the attack, likely a few days. Such survival suggests other group members provided care. The extent of trauma would have caused severe pain, blood loss, and swelling. Death likely followed from internal bleeding, brain injury, or organ failure.

The study also documented older injuries unrelated to the fatal event. The teen had a healed fracture in the smallest toe of the left foot and a joint disorder in the right ankle. These conditions support previous findings that serious lower limb problems limited mobility and survival prospects among prehistoric foragers.

Il Principe received an elaborate burial. His group placed him on a bed of red ocher and adorned him with a headdress made from hundreds of perforated shells and deer teeth. Ivory pendants and a flint blade imported from what is now southern France accompanied the body. A lump of yellow ocher lay near the injured shoulder and jaw. Such treatment marks one of the earliest formal burials in the cave and stands out within the Gravettian record.

Evidence for direct attacks by wild animals appears rarely in the fossil record of early modern humans, despite proof that people hunted dangerous carnivores. This case provides clear skeletal signatures of a lethal encounter and shows how careful reanalysis of museum collections can yield new insights decades after excavation.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.