Archaeologists have found new evidence showing early transport and long term use of a wild potato across the American Southwest more than 10,000 years ago. The study, published in PLOS One, focuses on Solanum jamesii, often called the Four Corners potato. Researchers argue sustained harvesting and deliberate movement of this plant marked early steps toward domestication.

Solanum jamesii grows today from northern Mexico into Utah and Colorado. Botanists place its natural origin farther south near the Mogollon Rim in Arizona and New Mexico. Many modern populations in Utah and Colorado sit near archaeological sites rather than across wide natural habitats. Genetic work over the past decade traced several northern groups back to southern source populations. Such patterns point to human transport over long distances.

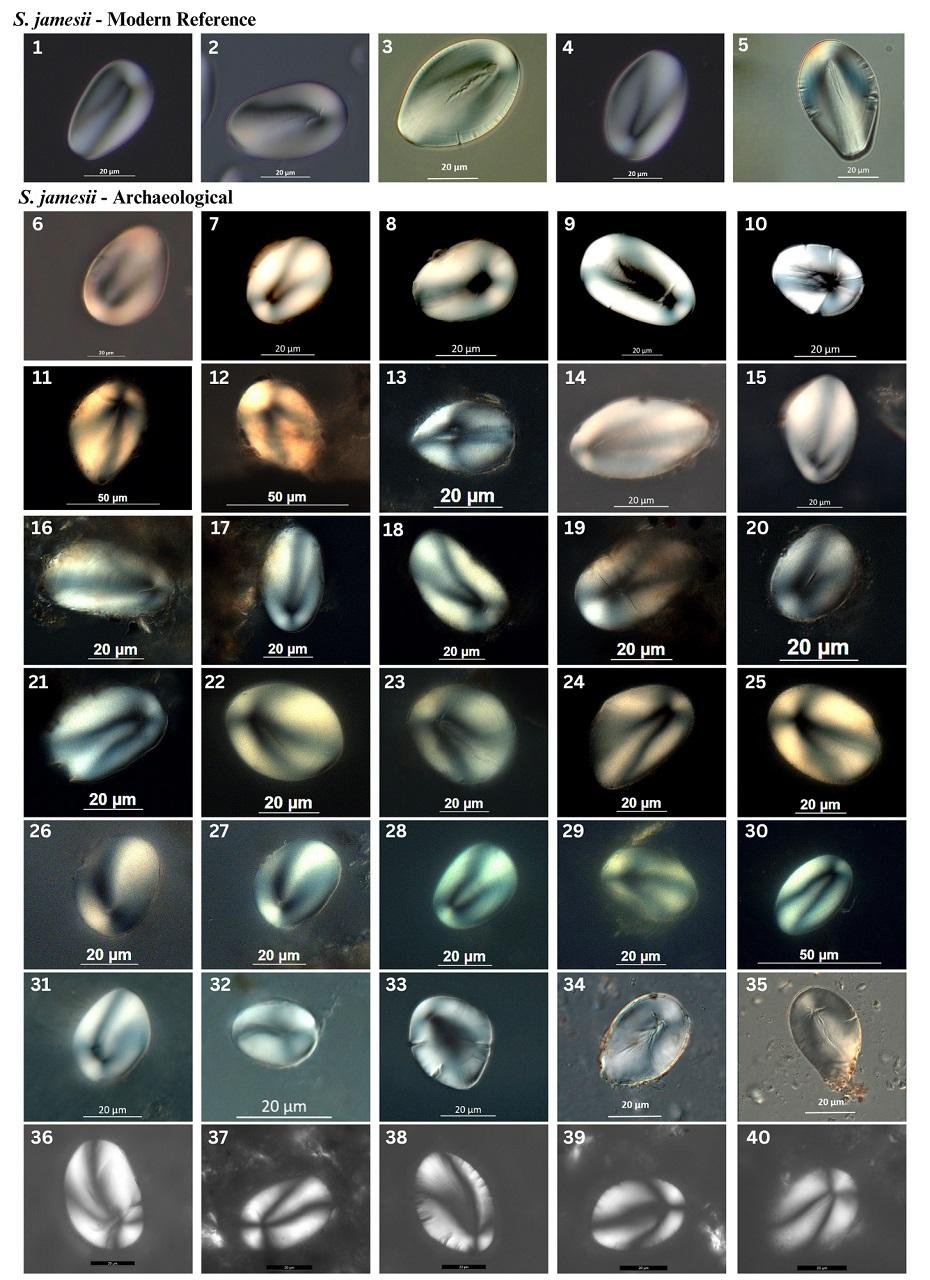

To investigate ancient use, the research team examined 401 ground stone tools from 14 sites. These tools included manos and metates used for grinding food. When people process tubers on stone, microscopic starch granules lodge deep inside surface cracks. Scientists extracted residue from tool surfaces and compared granules with modern reference samples.

Granules from Solanum jamesii appeared on tools from nine sites. Four locations showed repeated use beginning about 10,900 calibrated years before present. Many of these sites lie near the present northern edge of the plant’s range in southern Utah, southwest Colorado, and northwest New Mexico. Places such as North Creek Shelter, Mesa Verde, and Chaco Canyon produced strong evidence of processing.

Researchers view two behaviors as signs of early domestication: regular human use and movement beyond natural habitat. Evidence from stone tools, plant genetics, and site locations fits both conditions. Some northern plant groups also show traits linked with human selection, including greater tolerance to freezing and changes in tuber dormancy and sprouting. Scientists plan future genomic work to test for clear signals of artificial selection.

Nutritional data help explain interest in this tuber. Compared with common red potatoes, Solanum jamesii offers more protein, higher caloric value, and greater fiber and mineral content. Dried tubers store well and travel easily, traits useful for mobile communities across the Colorado Plateau.

The project also included interviews with 15 Diné elders. Nearly all recognized the plant, knew harvesting spots, and described preparation methods. Several elders spoke about mixing tubers with white clay called glésh to reduce bitterness. Women often described present day use and preparation knowledge, while many men referred to past practices. Elders also described spiritual roles for the plant in water offerings and seedling ceremonies.

Together, archaeological residue, plant genetics, ecological surveys, and community knowledge form a consistent picture. Indigenous groups did more than gather wild plants. People transported, tended, and maintained Solanum jamesii across generations, shaping both plant distribution and regional food traditions in the Four Corners area over thousands of years.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.