Researchers have developed a new method to reconnect fragmented Egyptian funerary objects with their original context by analyzing precise measurements and three-dimensional surface data. The study, published in the journal Heritage Science, focuses on cartonnage mummy masks and related fragments that were removed from burial assemblages in the past and later dispersed among museums.

Many Egyptian artifacts entered collections during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with limited documentation. Excavation records were often incomplete. As a result, fragments of the same object sometimes ended up in different institutions. Curators have long relied on visual comparison to suggest links between pieces, but visual assessment depends on subjective judgment. The new research replaces visual comparison with measurable criteria.

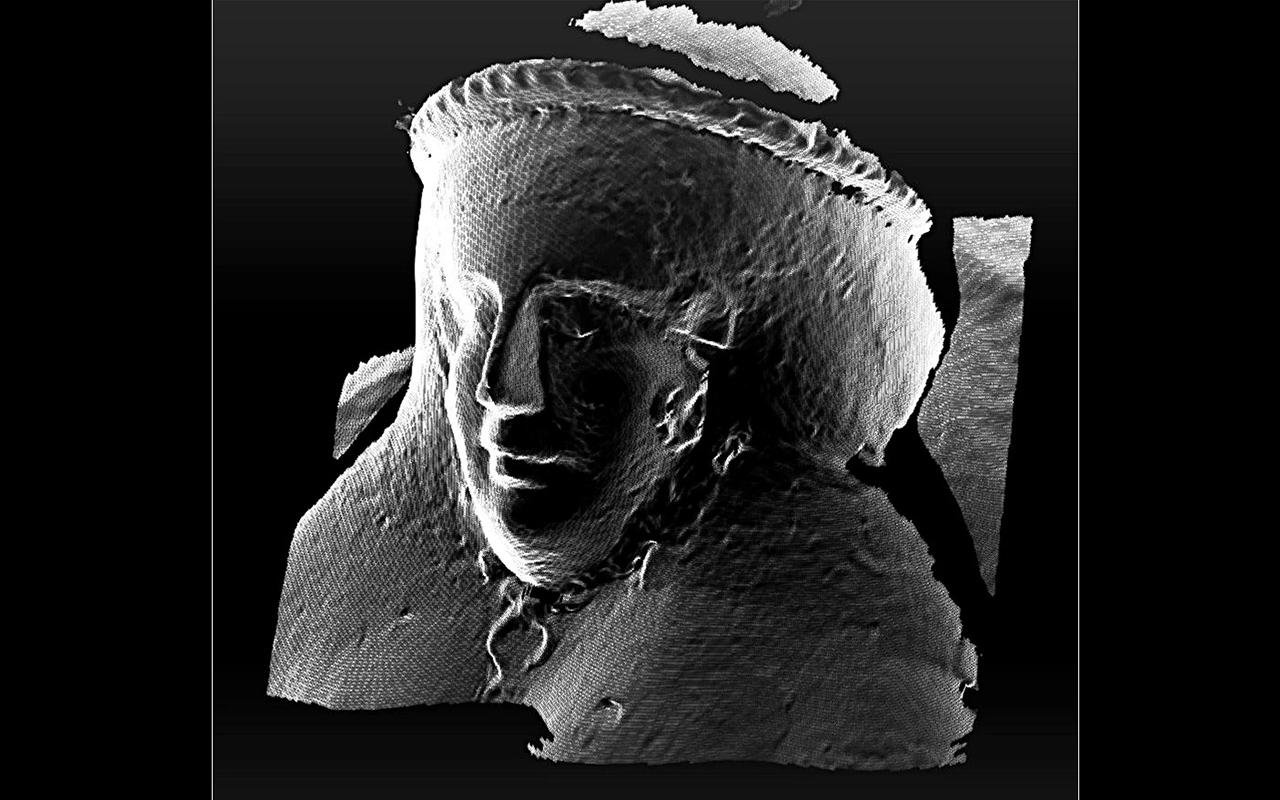

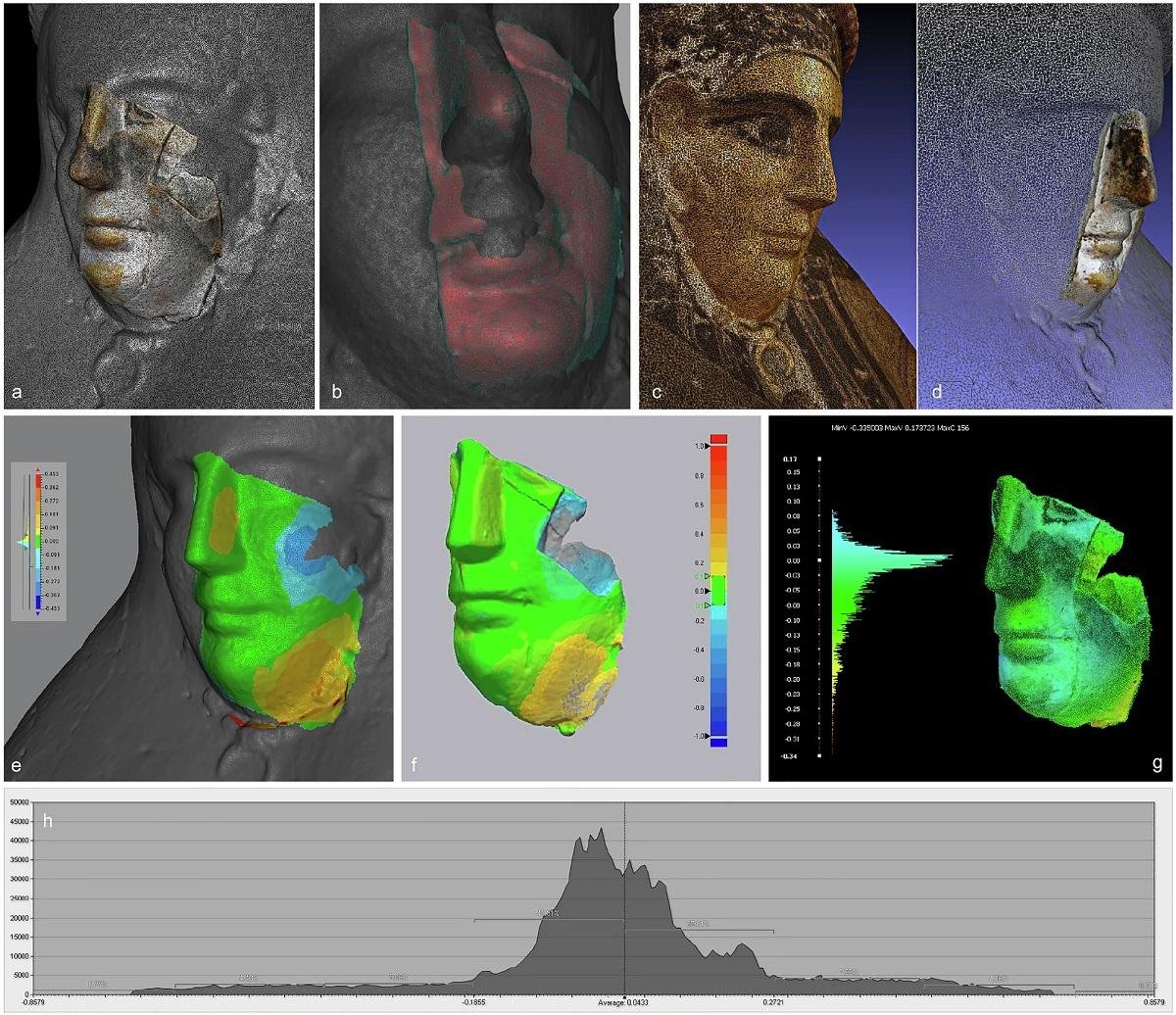

The team applied metrological analysis, which means they recorded detailed dimensions and surface geometry of fragments using three-dimensional scanning. They examined edges, curvature, thickness, and surface features. Each fragment produced a digital model. Researchers then compared these models to identify matching break lines and consistent proportions.

The case study centered on fragments of cartonnage mummy masks. Cartonnage consists of layers of linen or papyrus coated with plaster and painted. These masks were molded to cover the face and upper torso of the deceased. Over time, many broke into pieces. Some fragments still carry painted decoration, while others preserve only structural layers.

The researchers analyzed multiple fragments held in different collections. They measured curvature radii and edge profiles and mapped surface contours at high resolution. When two fragments belonged to the same original mask, their break edges aligned with minimal deviation. The team quantified this alignment by calculating distance values between digital surfaces. Small deviation values supported a physical match.

In one instance, fragments stored in separate museums showed consistent curvature across the forehead and cheek areas. Their edge geometries fit within narrow tolerance ranges. Digital overlay confirmed alignment along fracture lines. These results provided strong evidence that the pieces once formed part of a single mask. The method moved beyond stylistic similarity and relied on measurable physical data.

The study also addressed provenience attribution. When fragments share identical structural features and manufacturing traits, such as layer thickness and surface preparation, those traits help connect objects to a specific burial context. In cases where excavation archives contain partial descriptions or photographs, digital models offer a way to test whether surviving fragments correspond to documented finds.

The authors argue that metrological analysis provides a reproducible framework. Other researchers can repeat measurements and verify results. The approach reduces uncertainty linked to earlier collection histories. It also supports collaboration among institutions by allowing digital comparison without transporting fragile objects.

This research demonstrates how quantitative analysis reshapes the study of dispersed archaeological material. By focusing on measurable form and geometry, scholars rebuild connections lost during earlier collecting practices. Reuniting fragments improves interpretation of burial assemblages and strengthens the historical record for ancient Egyptian funerary art.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.