Researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences mapped more than 630,000 former charcoal kiln sites across Poland. The results show the size of an industry that supported metalworking, glass production, and other trades for centuries. The team combined airborne laser scanning with historical records, place names, and environmental data. These sources helped reconstruct patterns of forest use that written documents barely recorded.

Charcoal served as a primary fuel for high-temperature work before coal became common. Iron smelting, tool forging, nail production, and glassmaking required steady heat between about 500 and 800 degrees Celsius. Charcoal provided this range more effectively than raw wood. Resin-rich timber processed through carbonization also produced tar and pitch for sealing boats and treating leather. Ash from the process yielded potash, which people used in gunpowder production. Daily economic activity in medieval and early modern Poland relied on these materials.

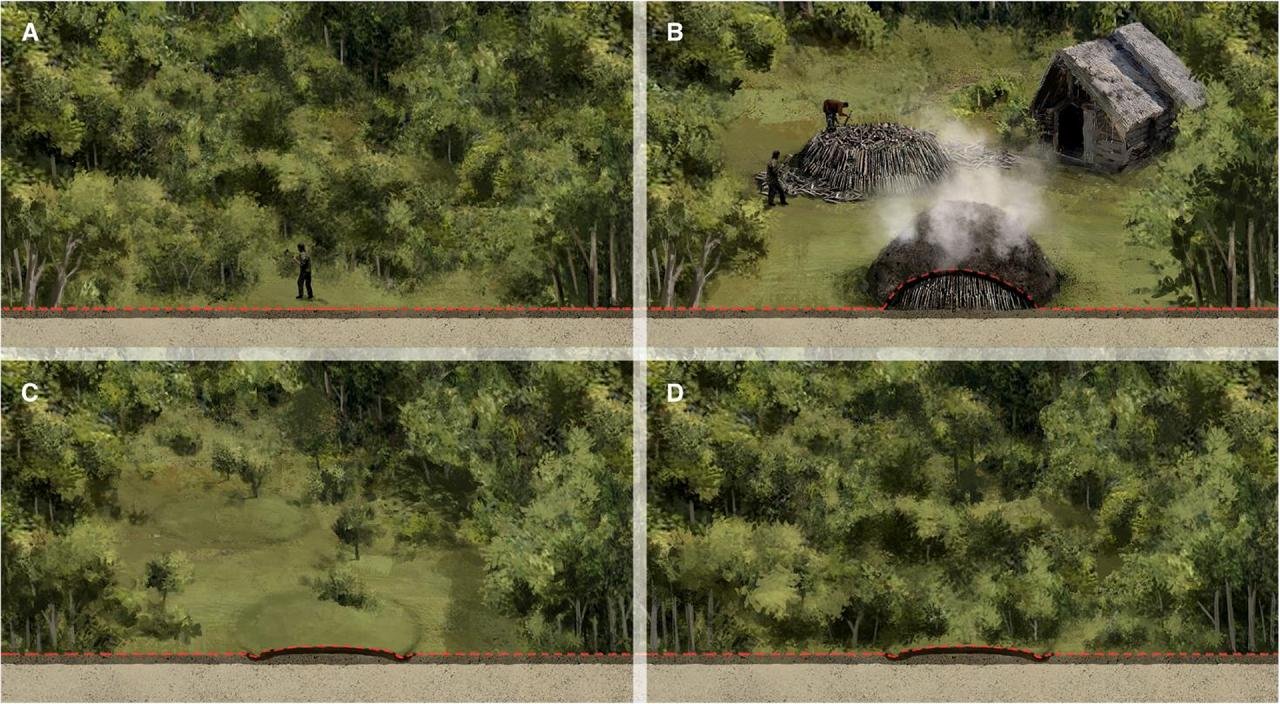

Workers followed a consistent production method. They stacked logs in a circular pile, often close to 10 meters wide. They covered the mound with turf and sand to restrict oxygen. Fire smoldered inside for 10 to 20 days at temperatures near 300 degrees Celsius. One burn consumed 200 to 250 cubic meters of wood, equal to timber from about half a hectare of forest. After each cycle, workers moved to a new location with fresh wood supplies. This mobile system left few permanent structures, which explains why earlier historians missed much of this work.

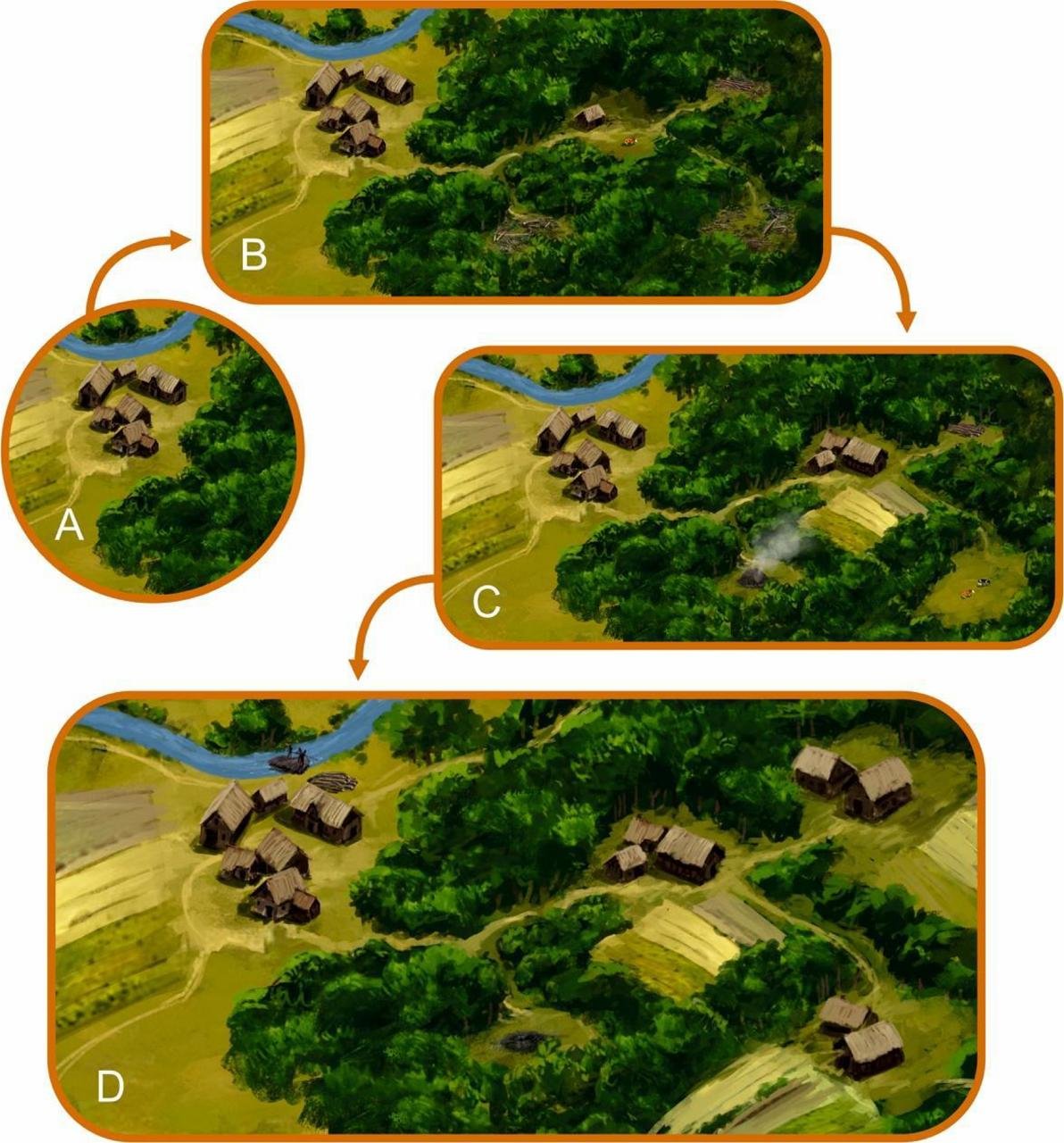

Forests rarely vanished from maps because cutters removed trees in shifting patches instead of clearing large areas for farming. Pollen records from lake sediments show repeated phases of forest thinning and regrowth in the same areas over long periods. Mapmakers marked the outer forest borders, while interior zones went through cycles of cutting and recovery. Later regrowth covered most surface traces of kiln activity.

Airborne LiDAR scanning enabled national-scale mapping. Former kiln sites appear as shallow circular depressions beneath tree cover. A graduate researcher spent two years reviewing datasets and marked more than 630,000 features, most in present day forests. Many other sites likely disappeared under plowed fields or urban development. Soil studies at selected locations show long-term chemical change. High heat sterilized soil layers and altered acidity. Even after a century, former kiln soils contain fewer microbes and higher concentrations of some heavy metals, including cadmium.

Language also preserved evidence of this work. Many settlement names recorded before the seventeenth century refer to charcoal burning, tar production, or related trades. Archival maps, written records, and onomastic research match the spatial patterns identified through laser scanning.

The research team included geographers, paleoecologists, historians, linguists, soil scientists, foresters, and GIS specialists. Their combined effort produced a national database scheduled for public release. Heritage specialists treat these kiln remains as part of industrial archaeology. The sites record long-term interaction between communities and forest environments.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.