Archaeologists have reexamined long-held ideas about burial practices in the Great Basin and found a broader pattern than earlier reports suggested. A study in American Antiquity compares cave and rockshelter burials in the lower Lahontan drainage basin of western Nevada with those in the neighboring Bonneville Basin of western Utah. Earlier work described the Lahontan area as unusual, with cave burials viewed as rare elsewhere. The new analysis shows a different picture.

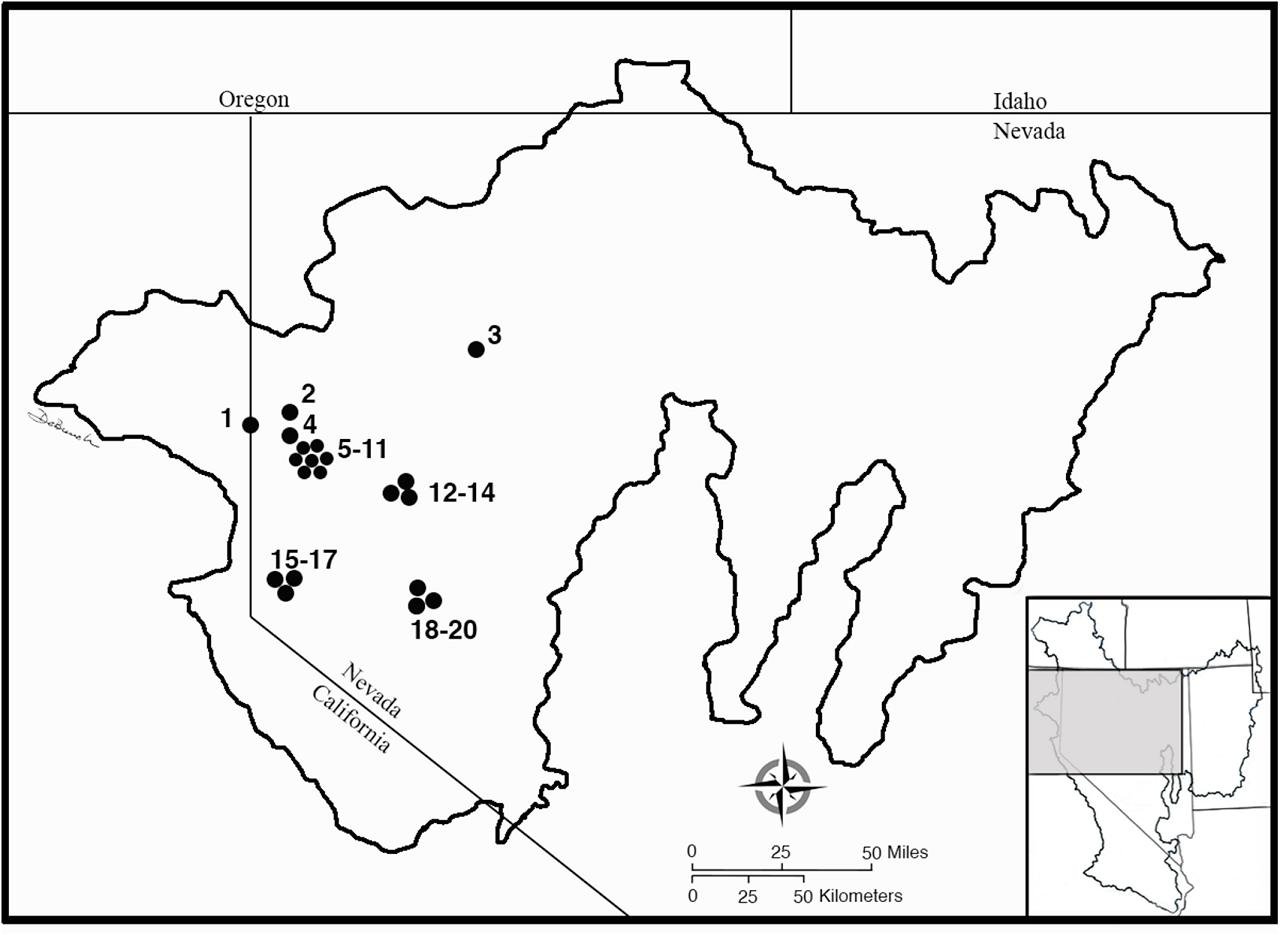

Researchers compiled records from excavated caves, rockshelters, and open-air sites in both basins. In the Bonneville Basin alone, the team documented 18 cave or rockshelter sites containing human remains, with a minimum of 91 individuals. Additional sites appear in the upper Lahontan region within the seasonal range of late Holocene groups linked to the Bonneville area. These numbers fall below totals reported for the lower Lahontan basin, yet they show burial in caves occurred on a regular basis across the wider region.

Most cave burials in the Bonneville Basin came from places where people also lived or carried out daily tasks. Hearths, tools, and food remains appear alongside human burials. Two locations, Lehman Cave and Snake Creek Cave, differ. Both functioned as natural trap caves and served mainly as burial places. More than three dozen individuals were interred in these spaces, with little sign of routine domestic use. Similar patterns appear in the Lahontan basin, where some caves served as homes or work areas while others held only the dead.

Open-air burials outnumber cave interments by a wide margin in both basins. Many lie within former house floors, near middens, or in separate outdoor cemeteries. Exact totals remain uncertain due to erosion, looting, and limited excavation. Even with these gaps, the overall record shows a flexible approach to burial location over thousands of years.

Occupation histories in both basins extend back roughly 14,000 to 13,000 years. Burial in caves, rockshelters, and open settings appears throughout this span. After about 5000 years before present, the number of burials increases in several areas. At the same time, many caves show repeated short term visits tied to food gathering, tool storage, and seasonal return to productive wetlands.

The higher count of cave burials in the lower Lahontan basin likely reflects population levels rather than a separate ritual system. Large marshes and wetlands supported reliable plant and animal resources, which drew groups back year after year. The region also contains hundreds of dry caves suitable for storage and temporary shelter. These environmental factors created more opportunities for burial in caves.

Ethnographic and archaeological evidence adds another layer. Northern Paiute communities in recent centuries tended to avoid caves containing the dead out of respect and fear. Some burial caves therefore predate Paiute occupation. Material culture and oral traditions point toward ancestral Washoe groups in parts of the Lahontan basin, along with other groups whose descendants now live mainly in California. Genetic studies of North American populations support episodes of movement and shifting territories during the last two millennia before European contact.

Taken together, the findings show cave and rockshelter burial formed part of a wider Great Basin tradition. Differences in numbers across regions align more closely with shifts in population and resource use than with isolated cultural practices.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.