A buried campsite in Alaska’s middle Tanana Valley offers fresh evidence about early human movement into North America. Excavations at the Holzman site along Shaw Creek reveal repeated human activity around 14,000 years ago, a period tied to major shifts in climate, animals, and landscapes near the end of the last Ice Age. The finds include stone debris, hearth remains, animal bones, and a large mammoth tusk, all preserved in layered sediments.

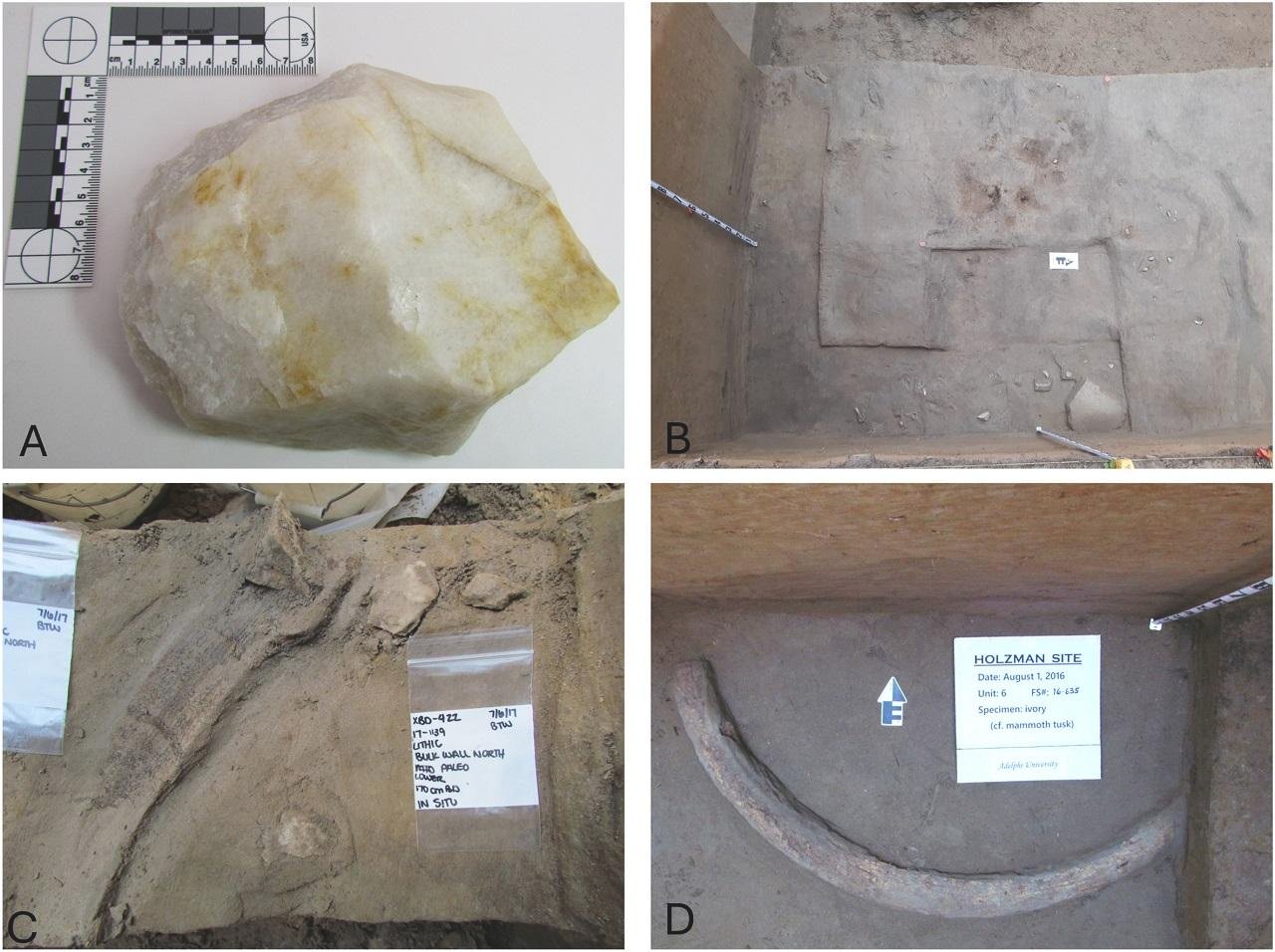

Researchers identified several occupation levels. The deepest level, dated to about 14,000 years ago, contains burned areas from campfires, bird bones, large mammal remains, and flakes struck from local quartz. A nearly complete mammoth tusk lay within this layer. These materials show food preparation, tool production, and use of mammoth parts at a single campsite. The setting sits near the meeting point of Shaw Creek and the Tanana River, an area rich in stone, water, and game.

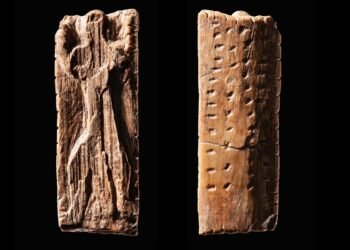

A slightly younger level, dated near 13,700 years ago, looks different. This layer holds dense concentrations of quartz fragments from tool shaping and clear signs of ivory working. People carved mammoth ivory into long rods and blanks. These rods rank as the earliest known examples of such tools in the Americas. Microscopic study of cut marks and shaping traces links production debris with ivory reduction. The pattern suggests focused manufacture rather than casual use.

The ivory technology draws special attention because similar carving methods appear later in Clovis sites farther south, dated near 13,000 years ago. Clovis culture is known for distinctive stone spear points, yet organic tools formed an important part of hunting gear. Ivory rods likely served as foreshafts or parts of composite weapons. The Alaska evidence indicates such techniques developed in the north before widespread Clovis expansion across mid-continental regions.

Stone tools from Holzman also add detail. Most came from nearby quartz sources, with some use of chert and siltstone. Analysis of flake scars and core reduction shows organized production sequences. People selected raw materials with care and transported some across the landscape. These choices point to mobile groups who moved through eastern Beringia while maintaining shared technical traditions.

The Tanana Valley holds deep windblown sediments and frozen ground, which protect ancient surfaces. Over several decades, work in this region has produced multiple early sites with dates older than 13,000 years. Holzman fits within this broader record and strengthens the view of Interior Alaska as a long-term homeland rather than a short stopover. Repeated visits to the same location suggest familiarity with local resources and seasonal patterns.

The timing also matters for migration models. By 14,000 years ago, people occupied parts of eastern Beringia. Movement south of the great ice sheets occurred sometime after, during a window between 14,000 and 13,000 years ago. Whether groups traveled mainly along coasts, through interior corridors, or by mixed routes remains under study. The Alaska data show technological roots for later Paleoindian traditions formed in northern environments among hunters who relied on mammoth, birds, and river valley resources.

Holzman therefore links daily camp life in Ice Age Alaska with cultural patterns seen far to the south a millennium later. Careful excavation, dating, and tool analysis turn a quiet creek bank into a key reference point for early American prehistory.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.