Researchers have produced a detailed ecological history of southern Africa between 180,000 and 30,000 years ago and used the record to reexamine links between climate and early human innovation. The results suggest cultural change followed different social and ecological pathways rather than a single response to shifting weather patterns.

The team built a regional vegetation and climate timeline using high-resolution pollen data from deep-sea sediment cores collected off both the eastern and western coasts of southern Africa. These marine records preserve continuous signals of plant cover on land. They avoid many of the gaps and local distortions found in cave or lake deposits. The pollen sequences show broad, synchronized trends across the subcontinent. Glacial phases brought cooler and wetter conditions, with expansion of Fynbos and Afromontane forests. Warmer interglacial periods saw drier landscapes and the spread of Nama Karoo vegetation.

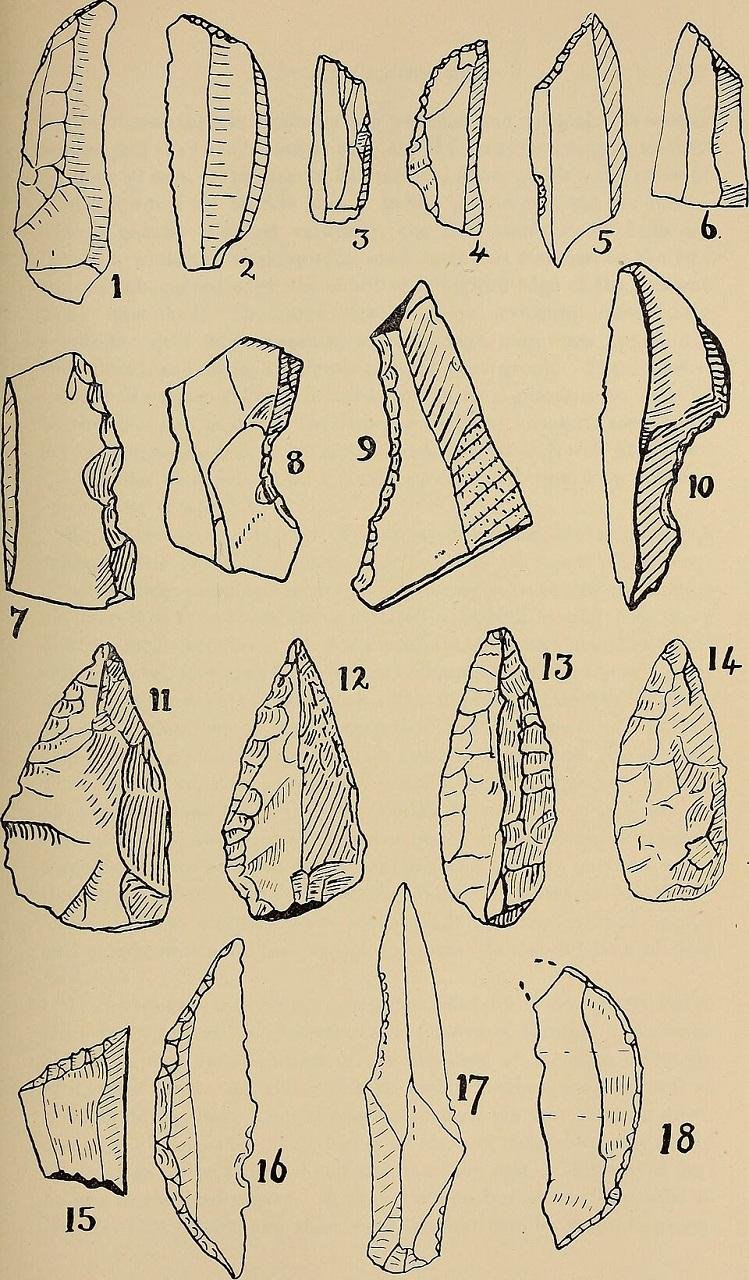

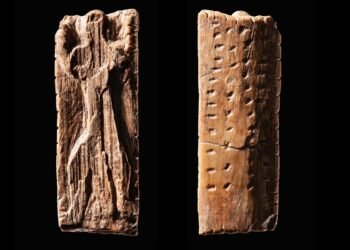

Researchers compared this ecological framework with archaeological evidence from two well-known Middle Stone Age traditions, Still Bay and Howiesons Poort. Still Bay appeared near the transition from Marine Isotope Stage 5a to 4, during a humid interval with high environmental productivity. Sites from this period contain finely made bifacial stone points and early symbolic objects such as engraved ochre and shell beads. These finds often come from areas where groups appear to have stayed in one region for long periods.

Howiesons Poort developed later, around 68,000 to 64,000 years ago, under conditions of strong climatic variability and fragmented habitats. Archaeological layers from this period show standardized blade production, backed tools, and early bow and arrow technology. Similar tool types occur across large parts of southern Africa at roughly the same time. Such wide distribution points to frequent movement of people, long-distance contacts, and exchange of knowledge and materials over hundreds of kilometers.

The contrast between these periods shows no single environmental trigger for innovation. Productive and stable settings coincided with dense local interaction and the appearance of symbolic practices and highly standardized point forms. Unstable and shifting settings aligned with wider social networks and rapid spread of new hunting technologies. Long stretches of favorable climate with little cultural change also appear in the record, which weakens the idea of a simple link between good conditions and innovation.

These findings fit a broader view of early Homo sapiens in Africa as a network of connected populations rather than one large, uniform group. Fossils from Morocco, Ethiopia, and South Africa display a mix of modern and older traits, which supports gradual development across different regions. Periods of isolation in environmentally stable refuges likely allowed local traditions to persist. Phases of increased contact helped spread ideas and tools between groups.

By placing cultural sequences within a shared ecological timeline, the study shows how social ties, mobility, and knowledge exchange shaped technological change. Climate shifts altered habitats and resource patterns, but social structure determined how groups responded. Innovation emerged through changing connections between communities as much as through environmental pressure.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.