Researchers from Universitat Jaume I, the University of Barcelona, and ICREA tested a digital method to study very fine engravings on Late Paleolithic portable art. Their work focused on three objects from Cova Matutano in eastern Spain. Archaeologists often use material from this site as a reference for comparing other Final Paleolithic images across the Iberian Mediterranean.

Fine engravings from this period often measure less than a millimeter in depth. Erosion, mineral growth, and natural cracks blur the difference between human marks and rock texture. Earlier studies relied on direct observation and hand drawings. Those approaches depended on personal judgment and sometimes led to errors.

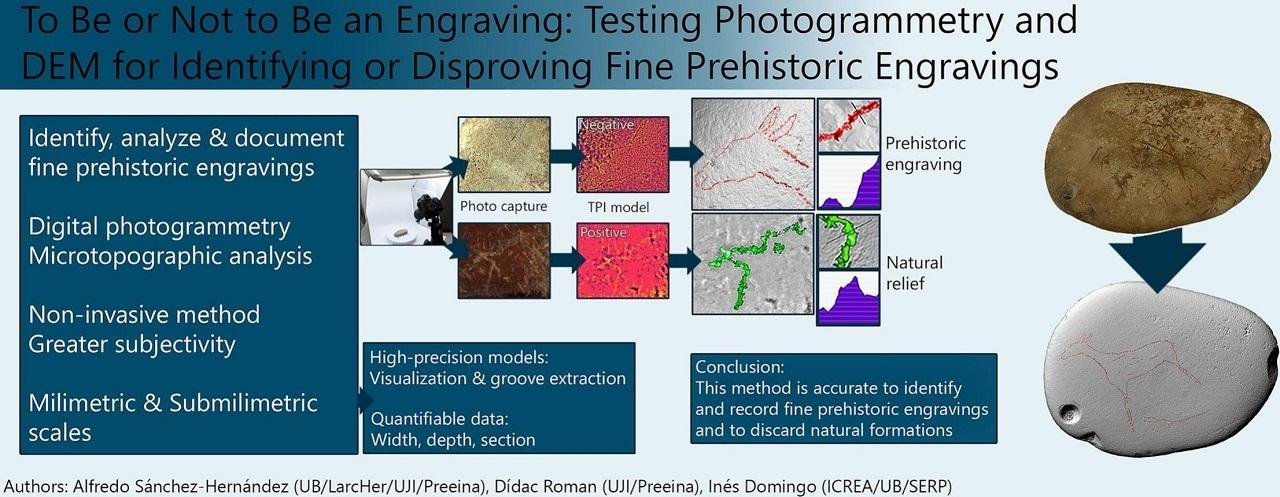

The team recorded each surface with close range photogrammetry. They produced dense 3D models and digital elevation maps. GIS software measured groove depth, width, and cross-section at a sub-millimeter scale. These measurements created a numeric record of each mark. Researchers compared shapes and profiles instead of relying only on visual impressions.

Before turning to archaeological pieces, the group ran controlled engraving tests on stone. They used different tools and varied hand pressure and motion. Each test mark entered a reference collection with known force and technique. When the team examined the Matutano pieces, they matched archaeological grooves against this dataset. The comparison helped separate deliberate cuts from natural surface features.

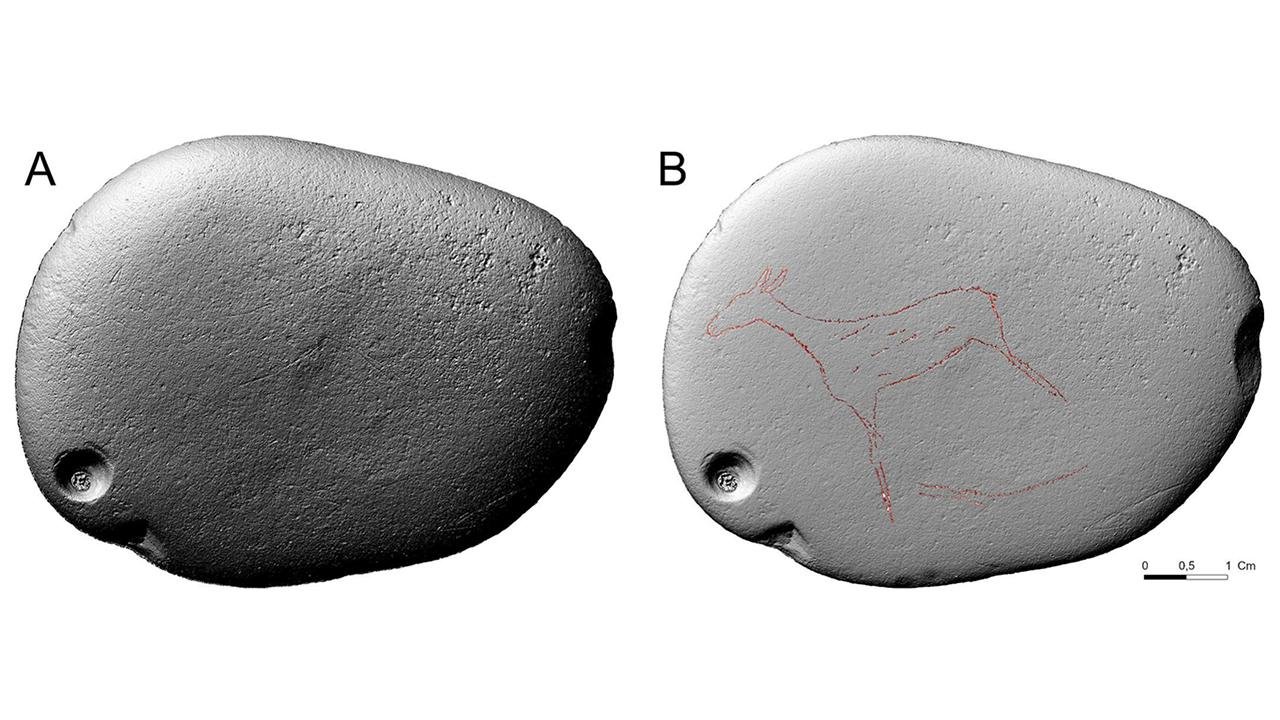

Results changed the reading of several motifs. One form described in earlier research as a human head matched natural relief when viewed through microtopographic data. A circular feature interpreted as an animal eye showed irregular depth and lacked the consistent V-shaped profile seen in experimental engravings. On another object, analysis revealed an uplifted tail on an animal figure, a detail missing from older tracings.

The study also documented variation within single figures. On one animal engraving, groove depth shifts along the body. Shallower lines appear along the back, while deeper cuts define the head and limbs. Experimental data link such variation to changes in pressure and tool angle. These patterns suggest deliberate technical choices tied to anatomy and working properties of the stone.

Accurate documentation matters for dating. Archaeologists compare style and technique across sites to build relative chronologies where direct dates remain absent. Numeric surface data reduce observer bias in such comparisons. Revised readings from Matutano align the assemblage more closely with other Final Paleolithic art in western Europe.

The method uses standard digital cameras and widely available software. High-resolution 3D models support conservation by limiting handling of fragile pieces. Researchers still checked a few areas under portable microscopes when digital data left uncertainty, especially on extremely faint marks.

By linking experimental reference marks with archaeological analysis, the project establishes a repeatable procedure for studying fine engravings. Work at Matutano shows how microtopographic recording refines interpretation of Paleolithic imagery and carving techniques.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.