Archaeologists working at Magna Roman Fort near Hadrian’s Wall have uncovered a small terracotta head from the third century CE. The object came from fill inside a defensive ditch along the fort’s northern edge. Volunteers Rinske de Kok and Hilda Gribbin found the piece on June 5, 2025, during a community excavation linked to a five-year research program supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

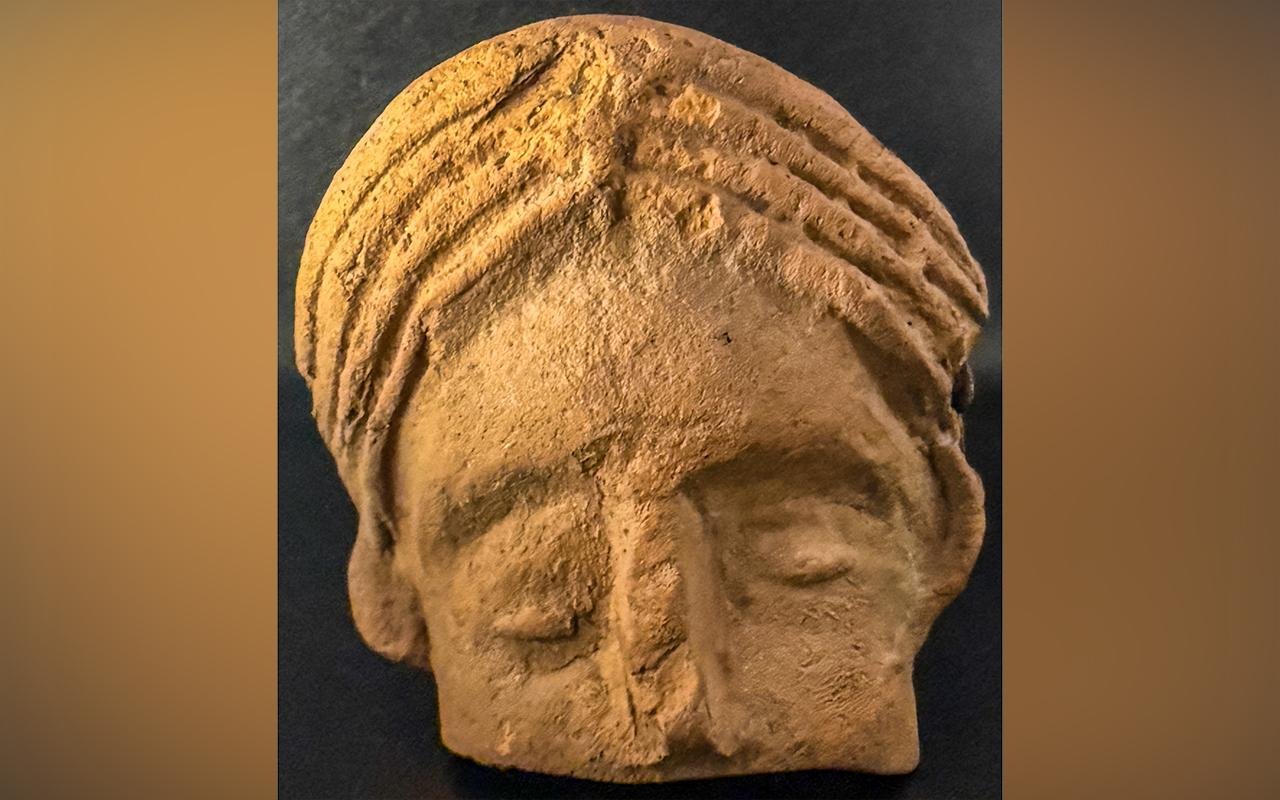

The head measures 78 millimeters high and 67 millimeters wide. Orange clay forms a female face with a center part and four plaited strands framing each side. Breakage below the nose removed the mouth and chin. Facial features appear uneven. Eyes sit at different levels, and ears lack careful shaping. Surface finishing looks rough rather than polished.

A Roman finds specialist who examined the object suggested production by a learner rather than an experienced craft worker. Poor symmetry and quick modeling point toward practice work made close to where people used or discarded such items. Transport over long distance would make little sense for an object with little market appeal.

Free-standing terracotta heads rarely appear in Roman Britain. Face pots, by contrast, turn up often on military and civilian sites. Magna has produced a similar head before. During the nineteenth century, a more refined terracotta head and bust came from the same fort. Museum records show the donation of the earlier example to the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne in 1982. Today, the piece sits in storage at the Great North Museum Hancock.

Comparison between both heads shows shared features. The hairstyle, general face shape, and proportions align closely. Archaeologists working on the current project think both pieces represent one figure. One possibility suggests an imported original served as a model, while a local craft worker tried copying the form in clay. Such copying would explain the lower quality of the newly found head.

Terracotta busts of women often served as votive offerings across many Roman provinces. Worshippers placed small figures in shrines, temples, or domestic spaces linked with household religion. Finds of this type remain uncommon in Britain, which adds weight to the Magna discovery. Repeated appearance of one female image at a frontier fort hints at focused devotion among soldiers, families, or traders living near the wall.

The older head also carries an unusual modern story. A woman named Mary Ann Henderson, the last member of a family living at Carvoran farm, owned the object during the late nineteenth century. She likely found the piece locally before selling the farm in 1885. Family possession continued for decades before donation to an antiquarian society. Long gaps between recovery and museum care often hide useful data, yet survival of the piece still allows present research.

The newly found head will go on display at the Roman Army Museum with other recent discoveries from the Magna project. Shoes made from leather, a silver ring, bone hairpins, glass beads, and a small Venus figurine will appear alongside the clay face. Study of these objects builds a clearer picture of daily life, belief, and local production along Rome’s northern frontier.

More information: Roman Army Museum & Magna Fort

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.