A limestone object recovered from the Roman settlement of Coriovallum, now Heerlen in the Netherlands, has provided rare evidence for how people played board games during the Roman period. The object, preserved in Het Romeins Museum, carries a pattern of incised lines on a flattened surface. Archaeologists long suspected a link to play, yet no known Roman or earlier European game matches the design.

Detailed use wear analysis focused on damage along the engraved lines. Microscopic abrasion appeared uneven, with some paths far more worn than others. Such patterns suggest repeated movement of small pieces across specific routes rather than random contact or decorative carving. Deliberate shaping of the stone supports an intentional function rather than casual marking.

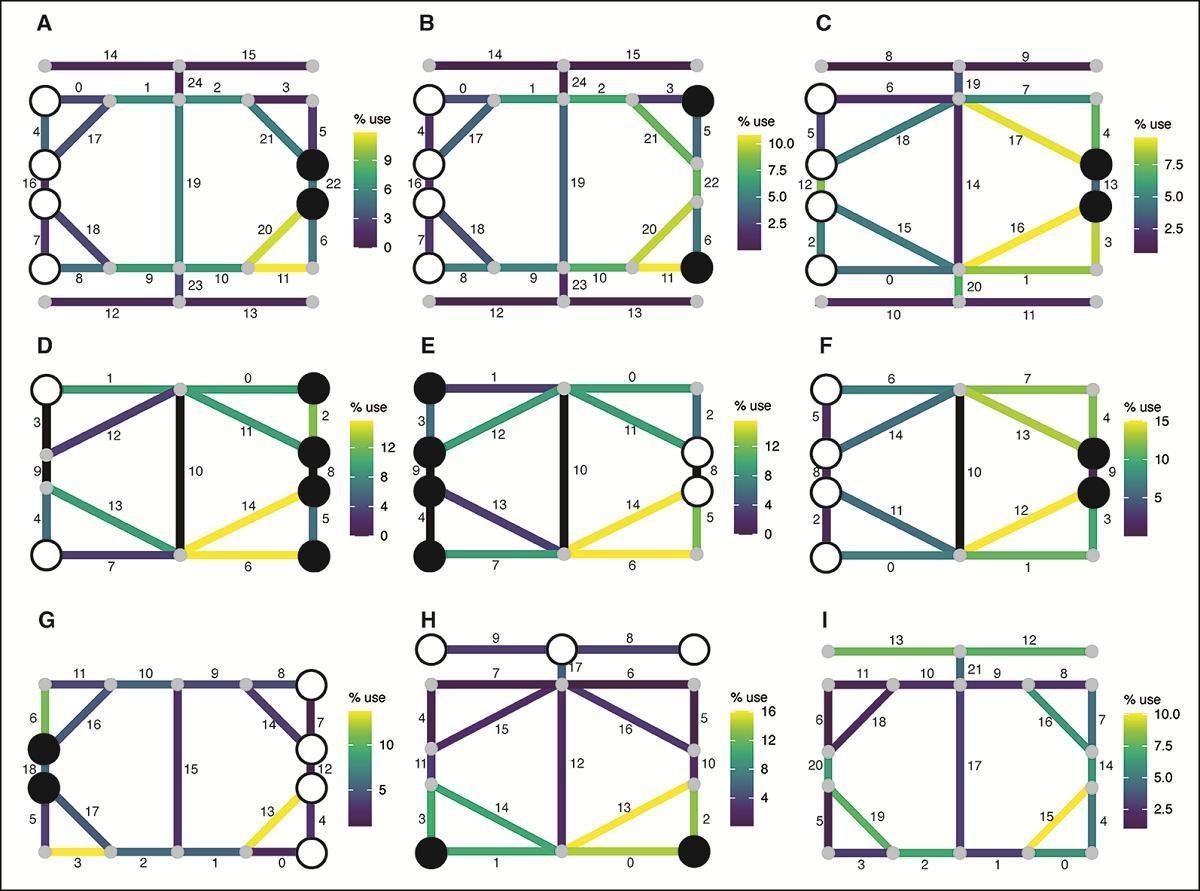

To test whether play could explain the wear, researchers combined archaeological observation with artificial intelligence-driven simulations. The team used the Ludii system, a platform designed to model historical board games. Two automated players competed against each other on a digital version of the stone board. The simulations drew from many rule systems recorded for small Northern European games, including examples from Scandinavia and Italy.

The results showed strong agreement between the observed wear and simulations based on blocking games. In this type of game, players aim to restrict an opponent’s movement rather than capture pieces. The simulated play repeatedly concentrated movement along the same lines seen on the stone surface. Other rule sets failed to reproduce the same uneven abrasion.

Blocking games hold a marginal place in the European archaeological record. Secure evidence appears only from the Middle Ages, several centuries after Roman control ended in the region. The Coriovallum board pushes the presence of this game type far earlier. The finding suggests Roman-era players experimented with rule systems not preserved in texts or art.

Ancient games often leave little trace. Many boards were scratched into soil or wood and used with temporary pieces. Survival depends on unusual choices, such as carving a board into stone. Single examples therefore pose challenges for identification, since traditional methods rely on repeated geometric patterns tied to known names or images.

The study, published in the journal Antiquity, shows how simulated play offers a new route forward. By matching wear patterns to modeled behavior, researchers gain a way to evaluate isolated objects without written references. The approach also allows reconstruction of playable rule sets grounded in physical evidence.

Beyond classification, this work adds texture to daily life in Roman frontier towns. Board games reflect social interaction, leisure time, and shared knowledge. The Coriovallum board shows continuity in play across centuries while also pointing to regional variation. Combining use wear analysis with artificial intelligence expands the ability to study past games and brings otherwise silent objects closer to lived experience.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.