Researchers tested how generative artificial intelligence portrays Neanderthals and found frequent errors, outdated ideas, and clear bias. The study appears in Advances in Archaeological Practice. Matthew Magnani from the University of Maine worked with Jon Clindaniel from the University of Chicago on the project. Both study archaeology and computational methods.

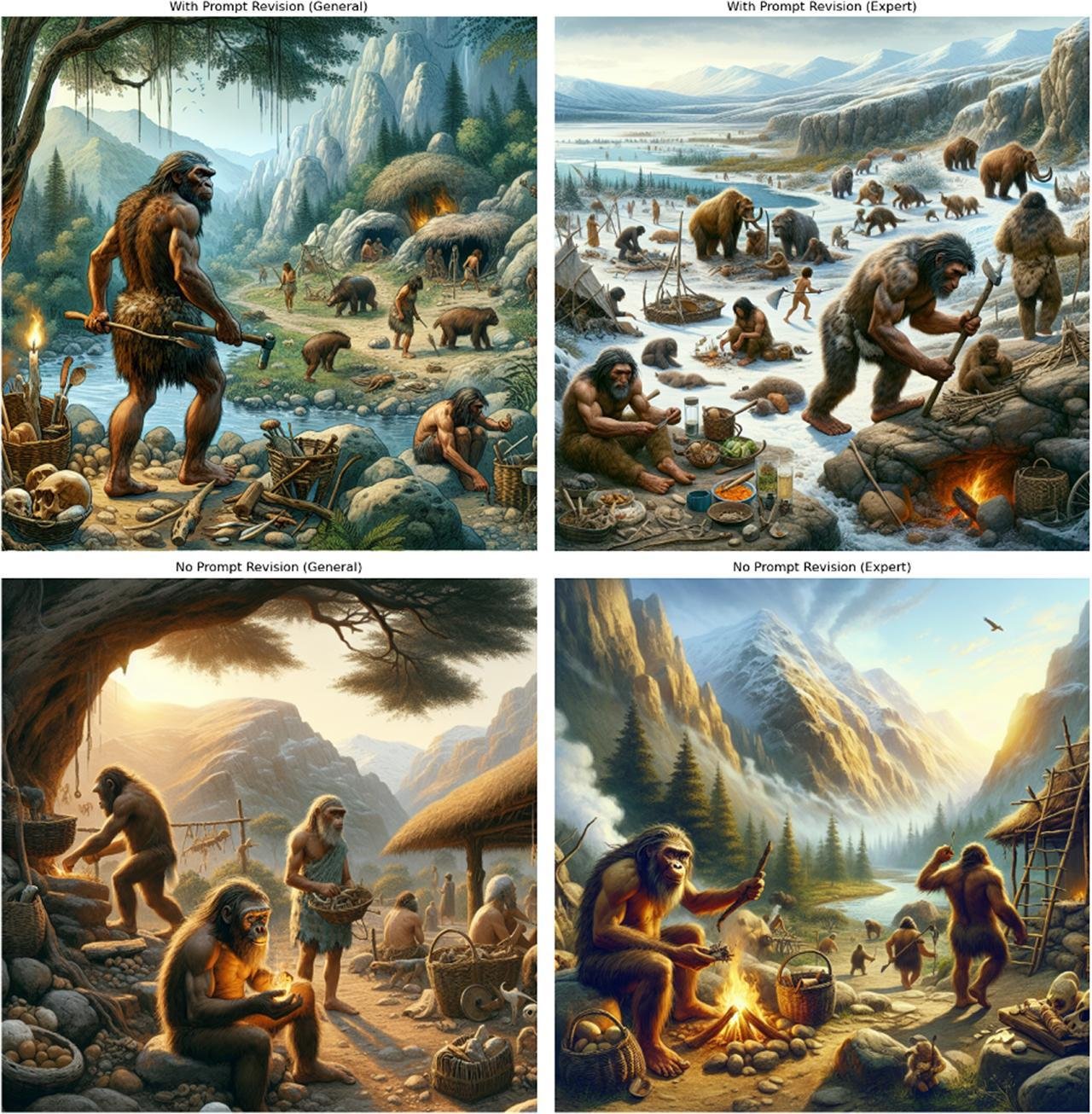

The team ran a large set of trials with text and image generators. They wrote four prompts and submitted each prompt one hundred times. Two prompts asked for scientifically accurate portrayals. Two prompts asked for general scenes without a request for accuracy. Some prompts included details about clothing, tools, or daily activities. The researchers used DALL E 3 for images and GPT 3.5 through the ChatGPT API for written descriptions.

The team compared every result with peer-reviewed research on Neanderthal life. They checked body form, clothing, tools, housing, food, and social groups. About half of the written responses did not match current archaeological knowledge. In one prompt group, more than eighty percent of the text conflicted with published research. The images showed similar problems.

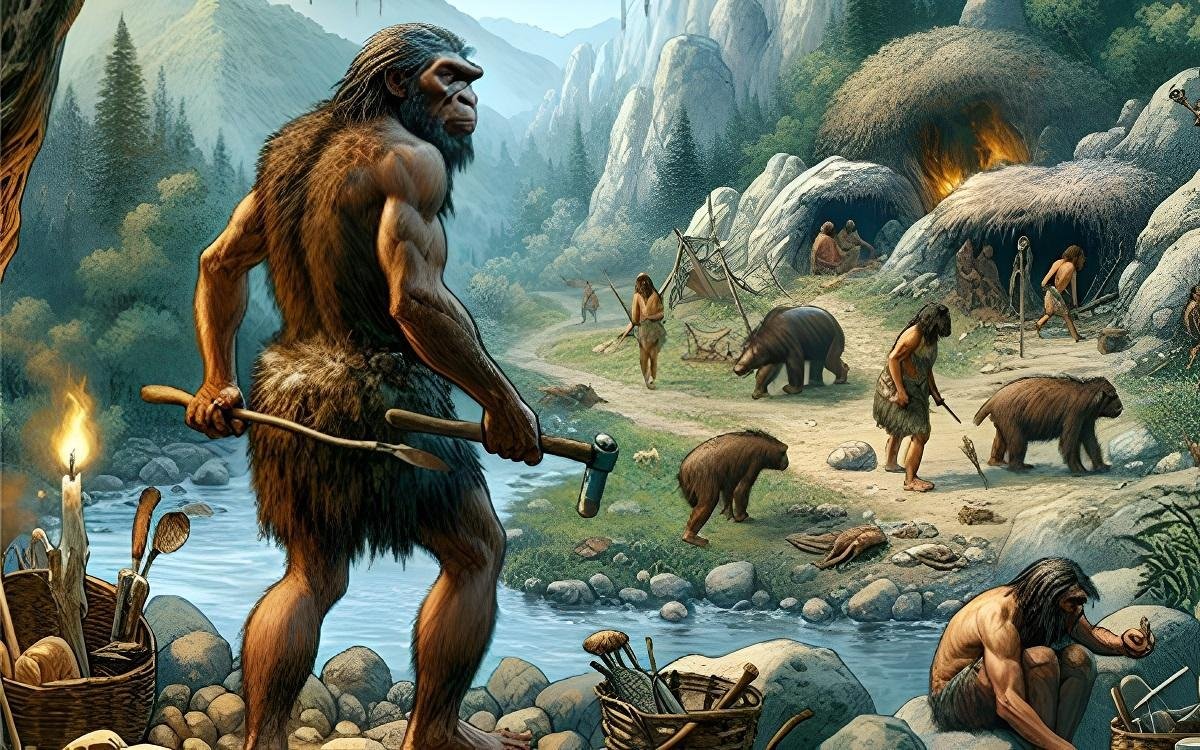

Many pictures showed Neanderthals with heavy body hair, bent posture, and ape-like faces. These traits match reconstructions from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Current research shows a more human body form and posture. Women and children appeared rarely in the generated scenes. This pattern reduced the range of social roles and daily tasks shown in the results.

Some outputs included objects from much later periods. A few images showed woven baskets, metal tools, or glass items. These materials do not belong in Neanderthal contexts. Written passages also described shelters and technologies without support from archaeological evidence. These details point to mixing of sources from different time periods.

The researchers traced patterns in the results to older academic and popular sources. The language in many written passages matched ideas common in the 1960s. The visual style of the images aligned more closely with reconstructions popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This gap suggests uneven use of source material across media types.

Access to research plays a role in these outcomes. Many recent archaeological articles sit behind paywalls. Older books and articles circulate more widely online. Training data drawn from easily available texts will favor older interpretations. Publishing systems and digital access therefore shape how the past appears in AI-generated material.

The study also points to social bias. Limited representation of women and children reflects patterns found in older writing and illustration. When such patterns repeat in generated content, they reinforce narrow views of past societies.

Magnani and Clindaniel present their approach as a model for further testing. Scholars in other regions or time periods can apply the same method. By measuring how closely generated material matches current research, researchers gain a way to track error and bias. This work supports more careful use of artificial intelligence in archaeology classrooms, public outreach, and research.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

So AI is full of $#!t, eh? And this is news because…?

To be fair, if you used Dali 3 for this, then you should not be surprised by the results!