A study in Accounting History examines how Londoners relied on weekly death totals during the Great Plague of 1665 and how those figures shaped both private choices and public policy. Researchers at the University of Portsmouth turned to the diary of Samuel Pepys to follow one man’s reading of the Bills of Mortality and his response to the rising toll.

The Bills listed burials by parish and cause of death. Clerks compiled the numbers each week and posted them in public places. Printed copies circulated among readers who wanted to track the spread of disease. In the summer of 1665, weekly plague deaths in London climbed into the thousands. Pepys recorded these totals in his diary and compared one parish with another. When numbers rose in areas near his home or workplace, he limited visits and reconsidered meetings. The statistics shaped his schedule, his travel, and his contact with others.

The research takes a microhistory approach, using Pepys’s detailed entries to trace how a literate and well-connected official processed official data. He did not accept the numbers without question. He noted doubts about undercounting and flaws in reporting. Yet he treated the figures as serious evidence of risk. He read John Graunt’s earlier study of the Bills, which analyzed years of mortality data and produced one of the first mortality tables. Graunt showed patterns in life expectancy and death rates, laying groundwork for actuarial science and life insurance. During the plague year, this type of numerical reasoning entered daily life.

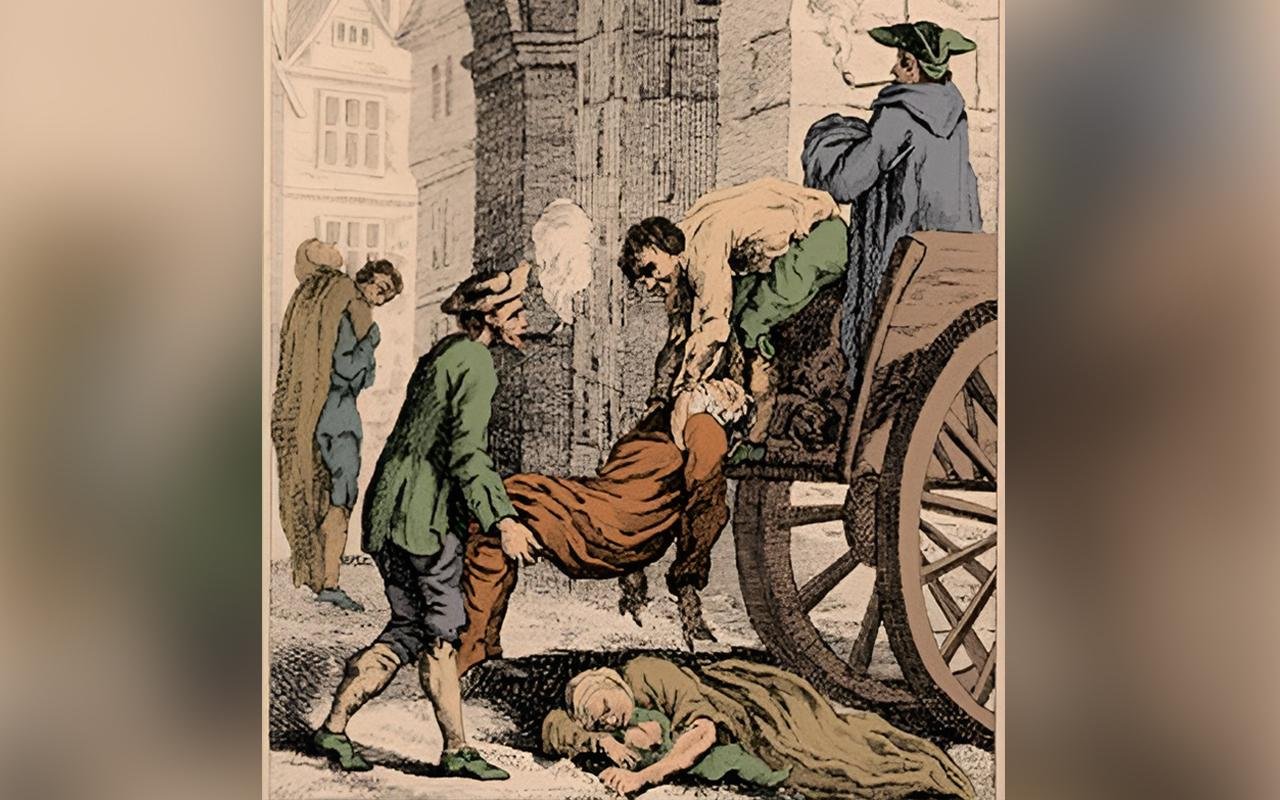

Authorities also relied on weekly totals. As deaths increased, officials ordered quarantines, closed theaters, restricted gatherings, and isolated infected households. The publication of mortality data supported these measures. Public access to numbers encouraged people to adjust their behavior in line with government orders. Counting deaths became part of governing the city.

The effects did not fall evenly across London. Wealthier residents who read the Bills and had money to travel left for the countryside when deaths peaked. Pepys considered leaving as well. Poorer families often lived in crowded housing and lacked the means to relocate. Many continued working in infected districts. Malnutrition and limited medical care increased their risk. When physicians fled the city, treatment became harder to find for those who stayed. The same statistics that guided departure for some reinforced confinement for others.

Pepys described shuttered shops, suspended entertainments, and rumors about cures. He recorded fear, economic strain, and later relief when deaths declined and trade resumed. Throughout these entries, the weekly Bills appear as a steady reference point. Numbers and personal reflection run side by side in his account.

The study argues that data-driven public health did not begin in the modern era. In seventeenth-century London, printed death totals informed private decisions and justified state intervention. The plague year shows how statistical reporting, government authority, and personal freedom intersected long before contemporary health systems took shape.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.