A team of researchers has uncovered fossilized feces near Stonehenge, providing fresh insights into the seasonal feasts conducted by the builders of this ancient monument.

The findings at Durrington Walls, a significant Neolithic settlement in Britain located a mere 1.7 miles from Stonehenge, are shedding light on the dietary habits and parasitic infections prevalent among the builders during the construction of this iconic site around 2500 BCE.

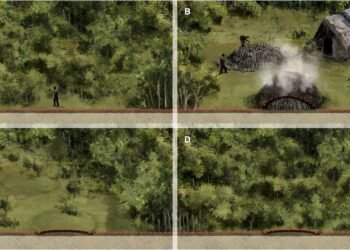

Durrington Walls, believed to be the campsite for Stonehenge’s builders during its main construction phase, has yielded a treasure trove of information.

The researchers, led by Piers Mitchell, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge, discovered fossilized feces in a refuse heap at Durrington Walls.

This Neolithic settlement, situated approximately 2.8 kilometers from Stonehenge, likely housed many of the workers involved in constructing the famous standing stones, considered by some as a solar calendar.

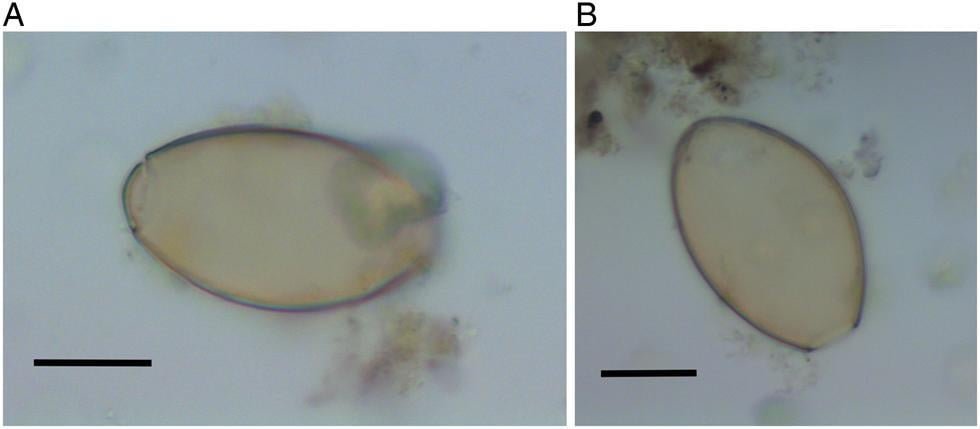

The team meticulously examined nineteen coprolites, or fossilized feces, recovered from the site, employing digital light microscopy to analyze intestinal parasite eggs.

Remarkably, five of the samples, constituting 26%, contained helminth eggs. Among these, one harbored eggs of the fish tapeworm, likely Dibothriocephalus dendriticus, while four contained eggs of capillariid nematodes.

This marks the first discovery of intestinal parasites from Neolithic Britain, a significant revelation considering their presence in the proximity of Stonehenge.

Piers Mitchell expressed the groundbreaking nature of the findings, stating, “This is the first time intestinal parasites have been recovered from Neolithic Britain, and to find them in the environment of Stonehenge is really something.” These parasitic worms, according to Mitchell, were likely ingested unintentionally by Stonehenge’s builders during communal winter feasts.

The researchers propose that, although the exact nature of the meat dishes served remains unclear, leftovers were shared with dogs at the settlement. It is suggested that the builders might have consumed eggs unknowingly by confusing offal for meat and undercooking it in clay pots. Previous studies have revealed that Stonehenge’s builders herded cattle from a distance of 62 miles, subsequently slaughtering these animals for their communal feasts.

The discovery of capillariid eggs in the coprolites holds significant implications. Such eggs typically indicate the consumption of internal organs (liver, lung, or intestines) of animals afflicted with capillariasis, passing through the human or dog gut without causing disease. This newfound evidence strengthens our understanding of both parasitic infections and dietary practices associated with this crucial Neolithic ceremonial site.

These revelations enhance our understanding of the complex interactions between humans, animals, and their environment during this pivotal period in history.

More information: Mitchell, P., Anastasiou, E., Whelton, H., Bull, I., Parker Pearson, M., & Shillito, L. (2022). Intestinal parasites in the Neolithic population who built Stonehenge (Durrington Walls, 2500 BCE). Parasitology, 1-7. doi:10.1017/S0031182022000476