In the scenic landscapes overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, a luxury villa from late antiquity in present-day Turkey is revealing new secrets, thanks to an international research team led by Professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen, an expert in archaeometry at the University of Southern Denmark.

The villa, dating back 1700 years, has been subject to excavation and examination in 1856 and the 1990s, but recent archaeological analyses have unveiled previously unknown aspects.

The team, including Thomas Delbey from Cranfield University, and classical archaeologists Birte Poulsen and Poul Pedersen from Aarhus University and the University of Southern Denmark, conducted archaeometric analyses, utilizing chemical analysis techniques to understand the composition and processing of various elements within the artifacts.

Their findings, detailed in the journal Heritage Science, focus on the examination of 19 mosaic tesserae, approximately 1600 years old, originating from the villa located in Halikarnassos, present-day Bodrum in Anatolia, Turkey.

Halikarnassos, renowned for the monumental tomb of King Mausolus, considered one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, was home to this luxurious villa with two courtyards and intricately adorned rooms featuring mosaic floors.

The mosaics showcased not only geometric patterns but also depicted scenes from Greek mythology, including Princess Europa’s abduction by the god Zeus in the form of a bull and Aphrodite at sea in her seashell. The stories of the Roman author Virgil were also represented, offering a rich tapestry of cultural narratives.

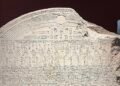

Inscriptions on the mosaic floors unveiled that the villa’s owner was Charidemos, and the construction occurred in the mid-fifth century. Mosaic flooring, a symbol of opulence during that era, involved the use of expensive materials such as white, green, and black marble, and imported stone, ceramics, and glass.

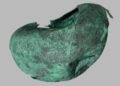

The team’s groundbreaking discovery lies in their chemical analysis of seven glass mosaic tesserae, revealing that six of them were likely crafted from recycled glass. The method employed inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, enabled the researchers to determine the concentrations of 27 elements, offering insights into the origins and composition of the glass. The analysis distinguished between base glass from Egypt and the Middle East, unraveling the intricate details of ancient glass production.

This revelation aligns with the historical context of late antiquity in Anatolia. As the Roman Empire’s influence waned, trade routes were disrupted or redirected, potentially causing shortages of goods, including raw materials for glass production. The scarcity, coupled with the ornate depictions on the villa’s floors, provides classical archaeologists with a nuanced understanding of the prevailing trends and artistic possibilities of that time.

Professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen remarked on the significance of the findings, stating, “It is of course difficult to extrapolate from only seven glass mosaic tesserae, but the new results fit very well with the picture of Anatolia in late antiquity.”

The research showcases the resourcefulness of ancient artisans in adapting to the challenges of their time, leaving an indelible mark on the mosaic floors that have endured for centuries.

University of Southern Denmark