A team of French archaeologists claims to have made significant progress in deciphering an ancient Elamite script found in southern Iran over a century ago.

Led by French archaeologist Francois Desset, the researchers believe they’ve partially unraveled this ancient script by examining eight silver cups adorned with symbols from the Linear Elamite writing system.

These silver cups had long been under the possession of a private collector but were recently made available to scholars for study. Professor Desset, who works at Iran’s University of Tehran and France’s Archeorient research laboratory, shared this development with DW.

The Linear Elamite script, for more than a century, remained an enigmatic script. Yet, now, this group of archaeologists suggests that they have managed to partially decode this ancient writing system, albeit with some reservations from other experts.

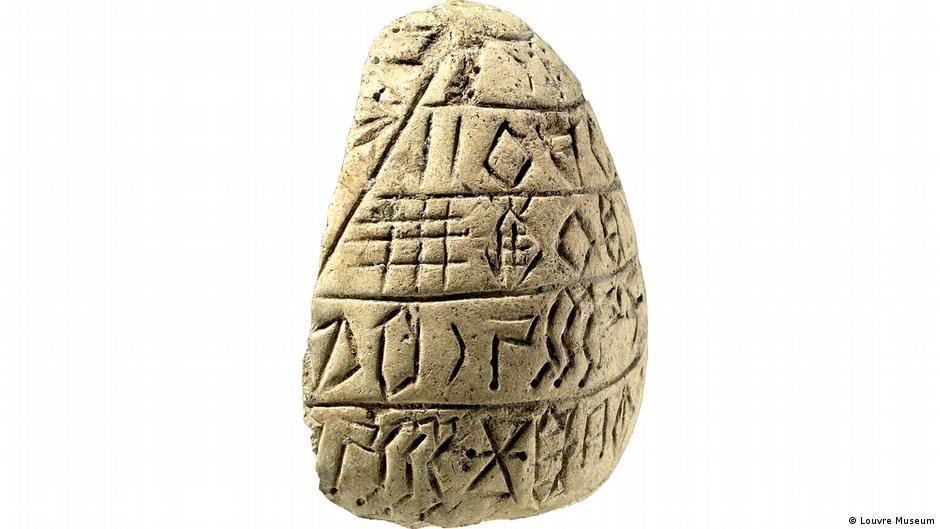

The first discovery of geometric patterns resembling diamonds and squares with dots and dashes was made by French scientists during their excavations in Susa, a region in southwestern Iran, back in 1903, as reported by a German broadcaster in late August.

Subsequently, researchers realized that Linear Elamite was among the four oldest known scripts in human history, alongside Mesopotamian cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphics, and the Indus script. The Elamite civilization utilized this writing system during the Bronze Age, between the late third and early second millennia BC.

Susa, a UNESCO World Heritage site, once served as the capital of the Elamite Empire and later as the administrative capital for the Achaemenian king Darius I and his successors, starting in 522 BC.

However, despite the long history of these discoveries, the diamond and square symbols have remained elusive in terms of decipherment, with only a small number of characters having been clearly interpreted.

According to Professor Desset, the groundbreaking aspect of their work lies in the revelation of the writing system’s nature. While others believed that Linear Elamite consisted of both phonographic and logographic characters, Desset argues that it is primarily a phonographic script, making it the world’s oldest script of its kind. This, in turn, alters our perspective on the evolution of writing.

Nevertheless, there is still some skepticism surrounding the complete decipherment of Linear Elamite. Michael Mader, a linguist at the University of Bern and scientific director of the Swiss Alice Kober Society for the Decipherment of Ancient Writing Systems, commented on this matter.

According to Mader, there are only 15 characters with known pronunciations and 19 plausible suggestions so far. Until all the characters’ functions and pronunciations are confirmed, Linear Elamite’s full decipherment remains uncertain.

As reported by the German broadcaster, the accuracy of Professor Desset’s findings is a topic of ongoing discussion, and specialists in ancient writing systems will convene in Norway in October to deliberate upon this discovery.

Susa, where these findings were made, boasts a history of continuous habitation dating back to around 5000 BC. The first urban structures in the region emerged around 4000 BC.

Notably, parts of Susa are still inhabited today under the name “Shush” in the Khuzestan province, situated on a strip of land between the Shaour and Dez rivers. The ruins and artifacts discovered in the area reflect the region’s remarkable heritage, with even the earliest potteries and ceramics bearing intricate designs of birds, mountain goats, and various other animals. — Tehran Times