An international research team led by the University of Oslo extracted and analyzed plant DNA from the sediments of Armenia’s “Aghitu-3” cave. The cave was used as a shelter by Upper Paleolithic humans between 40,000 and 25,000 years ago. A detailed DNA analysis reveals that the cave’s inhabitants may have used a variety of plant species for multiple purposes, including medicine, dye, and yarn.

The excavations were led by the Armenian National Academy of Sciences and the research project “The Role of Culture in Early Human Expansions (ROCEEH),” which is based at the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt. The findings were published recently in the Journal of Human Evolution.

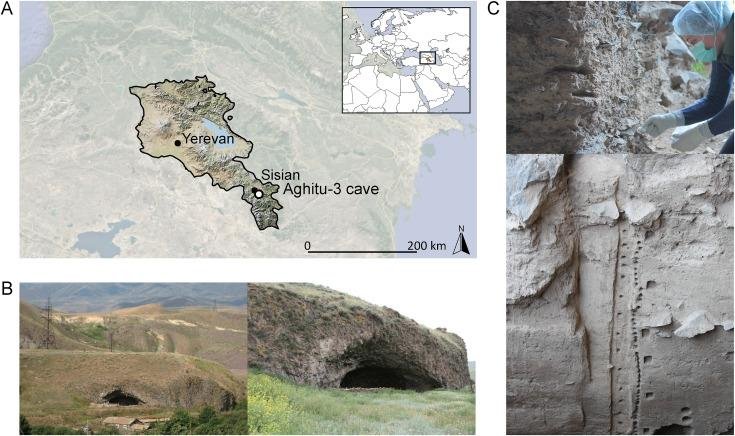

At first glance, nothing distinguishes the Aghitu-3 cave from the numerous other basalt caves in southern Armenia’s highlands. However, the 11-meter-deep, 18-meter-wide, and 6-meter-high cave holds something special: it is one of only a few sites in Armenia that contain Upper Paleolithic findings.

The cave sediments reveal information on human settlement from approximately 39,000 to 24,000 years ago.

“Stone artifacts, animal remains, bones, tools, shell beads, and charcoal from campfires have already been found in the cave,” said Dr. Andrew Kandel, the excavation’s scientific director from the ROCEEH project at the University of Tübingen, Germany. He continues, “Although we know that plants played a fundamental role in the lives of prehistoric people beyond serving as food, plant parts such as seeds, leaves, fruits, and roots are rarely preserved, since they are organic and usually decay quickly, making them difficult for us to study.”

In order to still be able to provide information about plant use in the Paleolithic period, the research team extracted plant DNA from the cave sediments. The DNA analyses show that during periods of intense human use of the cave, the sediments contained more genetic material from plants than during periods when people visited the cave less frequently.

“We therefore attribute most of the plants found to human involvement. People collected the plants during their daily activities. Once used, the remains of the plants were left in the cave where, to our delight, the DNA was preserved in the sediments.

By analyzing the DNA and comparing it with previously identified pollen types, we gain a more complete picture of the plants that were available to people and how people might have used them,” explains co-author Dr. Angela Bruch of the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt.

The researchers were able to identify a total of 43 plant orders—all but five of which were suitable for human use, according to the study. Some of the plants have medicinal properties, while others can be used as food, flavoring, or mosquito repellent. The discovery of DNA from plants that provide dyes or fibers suggests that people in this region used plants to make sewing thread or twine and to string up shell beads.

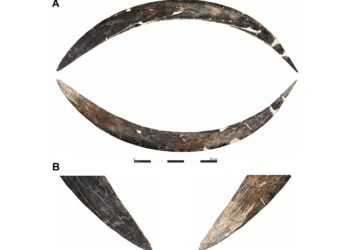

“This find fits into the overall picture of Aghitu-3 like a missing puzzle piece—needles made from animal bones were also found in the cave during our excavations. We now know with a high degree of probability that our ancestors sewed in the cave, and how they did it,” Kandel stated.

Plant DNA analysis from sediments is an exciting new technique for studying human behavior in prehistoric periods. “In the future, we will use this method at other sites to learn even more about our ancestors,” Bruch concludes.

Provided by Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum

More information: Anneke T.M. ter Schure et al, (2022). Sedimentary ancient DNA metabarcoding as a tool for assessing prehistoric plant use at the Upper Paleolithic cave site Aghitu-3, Armenia, Journal of Human Evolution. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103258