In southern Vietnam, researchers discovered and studied archaeological evidence of an ancient stringed musical instrument crafted of deer antler.

The instrument is 2,000 years old, dating from the pre-c Eo civilization of Vietnam, which lived along the Mekong River. It may be one of Southeast Asia’s earliest string instruments ever discovered.

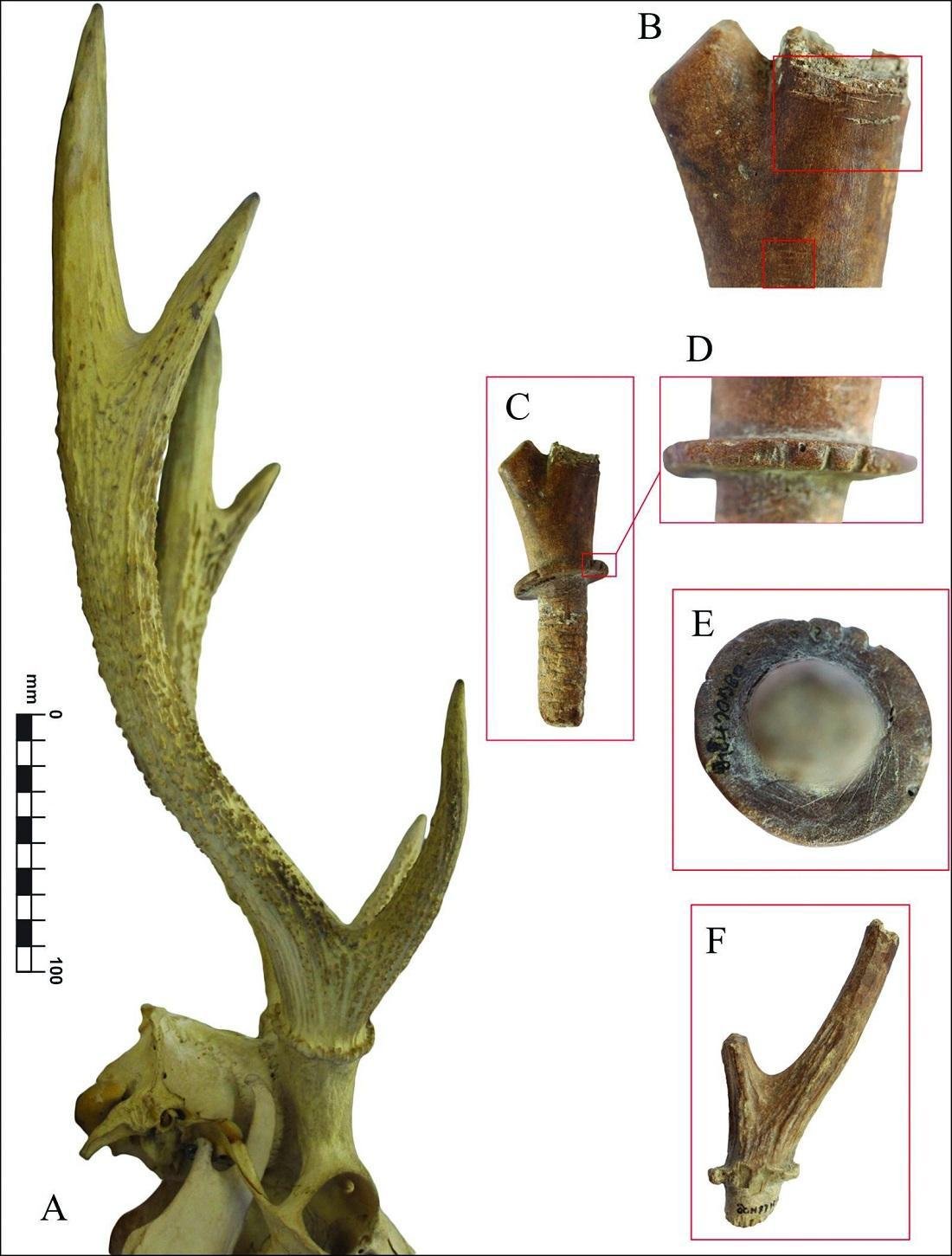

The item is a 35-centimeter-long piece of deer antler with a hole at one end for a peg, which was likely used to tune the string. The antler came from a Sambar deer or an Indian hog deer, both of which are native to mainland Southeast Asia.

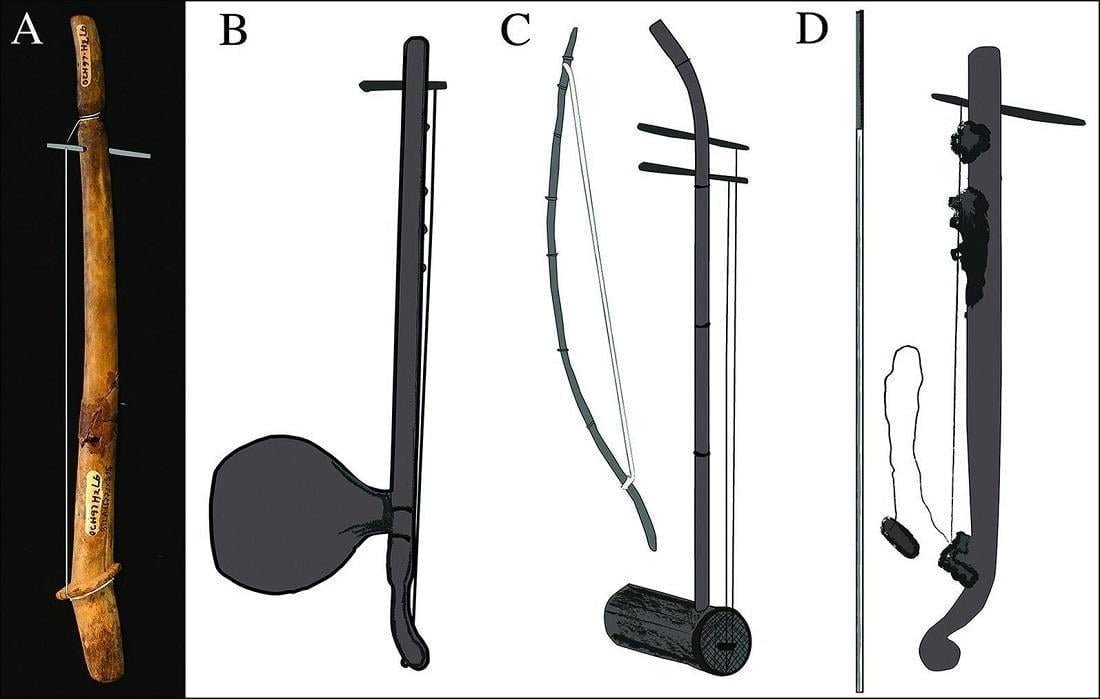

It looks like a single-stringed harp and may have been a great-grandparent of the complex musical instruments that people in Vietnam still play today.

Fredeliza Campos, a Ph.D. student from The Australian National University (ANU), and her collaborators, Vương Thu Hồng from Long An Museum in Vietnam and Jennifer Hull, from ANU, analyzed more than 600 bone artifacts.

“This stringed instrument, or chordophone, is one of the earliest examples of this type of instrument in Southeast Asia,” lead researcher, Fredeliza Campos said. “It fills the gap between the region’s earliest known musical instruments—lithophones or stone percussion plates—and more modern instruments.

“It is clearly established that music played an important role in the early cultures of this region. The striking similarities between the artifacts we studied and some stringed instruments that are still being played suggest that traditional Vietnamese music has its origins in the pre-historic past,” Ms. Campos added.

Researchers believe the instrument might have been played in a similar fashion to contemporary Vietnamese musical instruments such as the K’ný.

“The K’ný is a single string bowed instrument operated entirely by the player’s mouth, which also acts as a resonator. It may produce a vast range of sounds and tones, well beyond the chromatic scale commonly heard on a piano “Ms. Campos explained.

“This also suggests that the artifacts were made by specialists who are probably musicians themselves.”

The new study was published in the journal Antiquity.

More information: Fredeliza Z. Campos et al, (2023). In search of a musical past: evidence for early chordophones from Vietnam, Antiquity. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2022.170