A Byzantine-era woman’s skull discovered in central Italy revealed that this middle-aged woman had undergone invasive surgical procedures at least twice.

The skull was unearthed in the Lombard necropolis of Castel Trosino, which served as a burial ground from the sixth to the ninth century. With the fall of the Roman Empire, the site was transformed into a strategic Byzantine stronghold and was home to some of the wealthiest Lombard families.

Excavations at Castel Trosino have yielded lavish burial goods like gold and fine jewelry, but the research authors claim their latest discovery is “the first evidence of a cross-shaped bone modification on a living subject.”

According to the authors, this woman probably suffered from some kind of systemic condition. Periodontal disease was evident in her teeth, with acute abscesses and severe molar wear associated with tooth loss.

The CT scans also revealed evidence of hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI), a thickening of the inner side of the frontal bone of the skull. The disease is widespread in menopausal women and corresponds to the skull’s age.

It often accompanies other conditions like seizures, headaches, obesity, and diabetes. A healed perforating trauma is also consistent with frontal bone thickening, although such injuries are usually fatal, that wasn’t the case with this skull.

Alternatively, the procedures might have a ritualistic rationale. The Avar people of the Carpathian basin often used cranial scraping in this context, and the researchers note that the culture of the Longobard people of Castel Trosino was tightly intertwined with Byzantine culture.

However, they detected no evidence of trepanation practices among the Longobard people. The cut marks for that type of scalping have a distinctive pattern that differs from the cut marks on the woman’s skull.

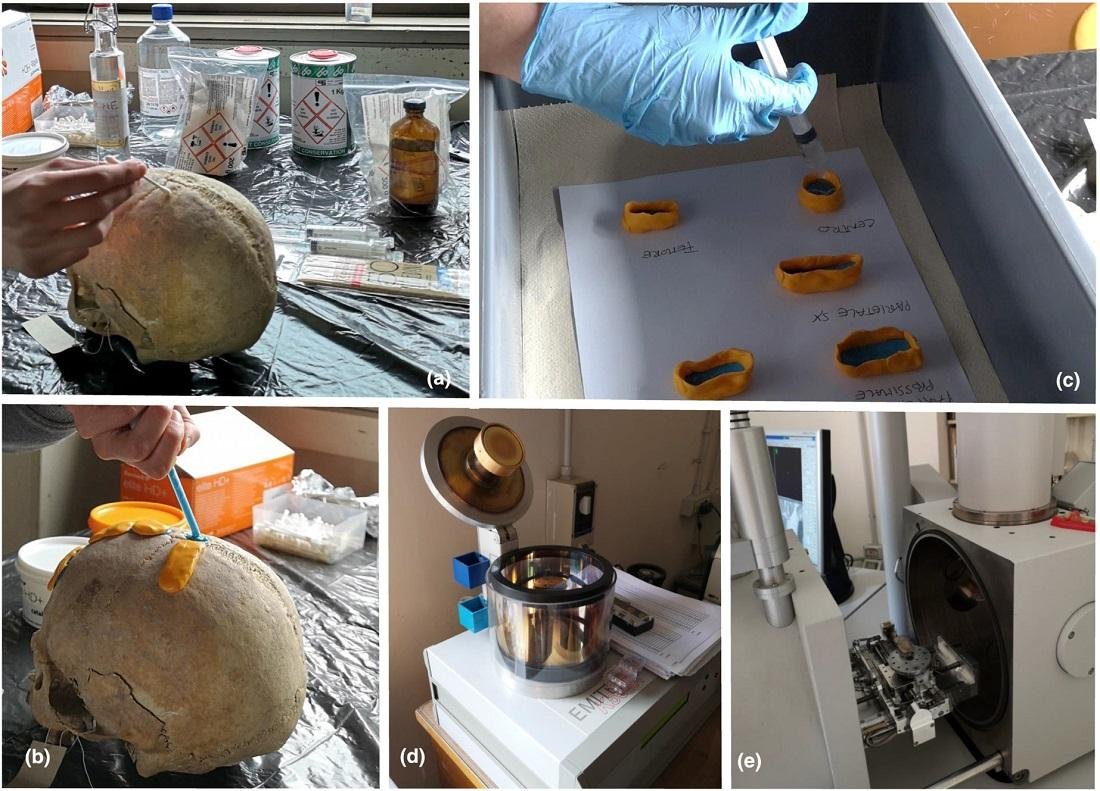

“We found that the woman had survived several surgeries, having undergone long-term surgical therapy, which consisted of a series of successive drillings,” study author Ileana Micarelli explained in a statement.

“The last surgery seems to have taken place shortly before the death of the individual,” said co-author Giorgio Manzi.

Despite the fact that the researchers found no clear evidence of “trauma, tumor, congenital disorder, or other pathology,” a medical explanation was ultimately determined to be the most likely.

“This represents one of the few pieces of archeological evidence of a trepanation surgery performed on Early Medieval women paving the path for future research on the rationale behind this dangerous surgical procedure in this period,” conclude the authors.

The study published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

More information: Micarelli, et al. (2023). An unprecedented case of cranial surgery in Longobard Italy (6th–8th century) using a cruciform incision. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 1– 9. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3202

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

This site is educational, archeology a field that amazes and teaches about the beginnings of the human race. Thank you for the interesting articles that are found on your site.