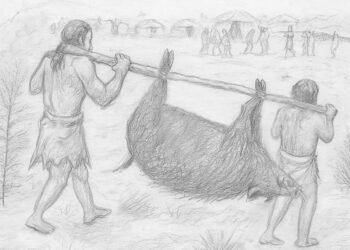

Around 125,000 years ago, Neanderthals gathered on the muddy shores of a lake in east-central Germany to hunt enormous elephants. They used sharp stone tools to harvest up to 4 tons of meat from each animal.

The findings, published in Science Advances, challenge previous assumptions about Neanderthal social structures, revealing a level of organization and communal living that was previously underestimated.

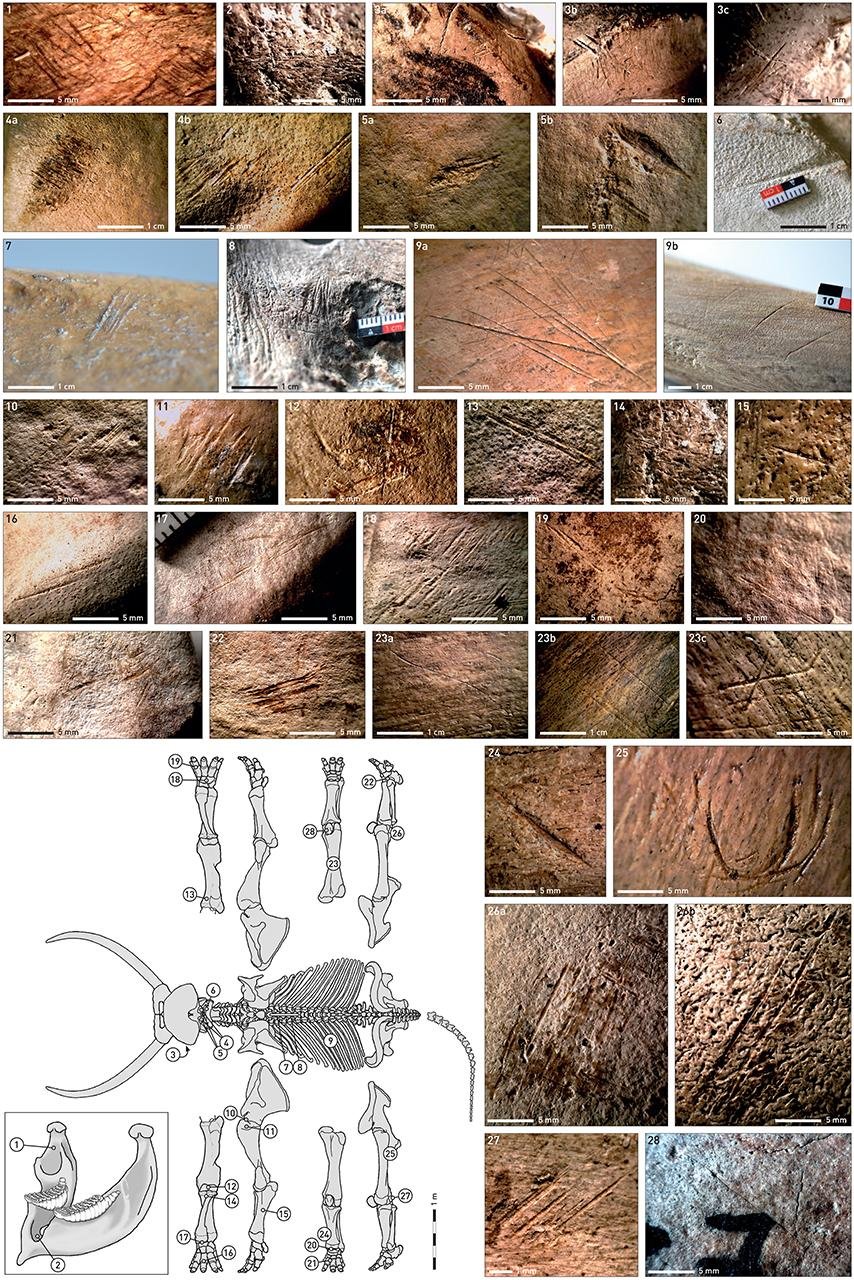

The revelation stems from a trove of animal bones and stone tools discovered in the 1980s by coal miners near the town of Neumark-Nord. Archaeologists, including Lutz Kindler and Sabine Gaudzinski-Windheuser from the MONREPOS Archaeological Research Center, spent a decade examining the remains, uncovering bones and tusks from over 70 mostly adult male straight-tusked elephants, an extinct species twice the size of modern African elephants. The site dates back to the Eemian interglacial, 75,000 years before the arrival of modern humans in Western Europe.

The extent of the butchery, as evidenced by strategic cut marks on nearly every bone, suggests a highly organized and thorough process. Wil Roebroeks, an archaeologist at the University of Leiden and study co-author, emphasizes, “They really went for every scrap of meat and fat.” The absence of scavenger gnawing indicates that Neanderthals utilized every part of the elephant, from meat to fat pads on the feet.

The researchers estimate that the meat from a single elephant could sustain 350 people for a week or 100 people for a month, challenging the conventional belief that Neanderthals lived in small, highly mobile groups of around 20 individuals. This discovery implies the existence of larger, more settled communities capable of both slaughtering and efficiently processing entire elephants.

April Nowell, an archaeologist at the University of Victoria, remarks, “This is really hard and time-consuming work. Why would you slaughter the whole elephant if you’re going to waste half the portions?” The findings indicate a level of competence and planning in Neanderthal behavior previously unrecognized.

The colossal scale of the elephant gatherings suggests the possibility of seasonal events or communal storage practices. Annemieke Milks, an archaeologist from the University of Reading, notes, “Maybe it’s a large, seasonal gathering, or they’re storing food—or both.” The researchers propose that Neanderthals were adept at dealing with significant amounts of food in one go, a unique advantage illustrated by the clarity of the archaeological evidence.

The implications extend beyond hunting practices to challenge existing views of Neanderthal sophistication. Gary Haynes, a retired archaeologist from the University of Nevada, Reno, says, “If one regional group of Neanderthals was capable of such behavior, other groups elsewhere surely would have been capable, too.” The prevailing image of Neanderthals as primitive beings is evolving, with evidence suggesting adaptability to various environments and climates.

Adult male elephants, which roamed alone without the protection of a female-led herd, were likely targeted, requiring a high level of coordination and planning in the hunt. Britt Starkovich, an archaeologist at the University of Tübingen, comments, “Neanderthals knew what they were doing. They knew which kinds of individuals to hunt, where to find them, and how to execute the attack.”

The findings challenge the perception that Neanderthals lived in small, nomadic groups. Instead, the evidence suggests the possibility of larger, more settled communities capable of collaborative endeavors. The study’s co-author, Wil Roebroeks, affirms that Neanderthals were not merely primitive beings, stating, “This lets us imagine Neanderthals as more like modern humans rather than as humanoid brutes, as they once were interpreted.”