A team of researchers led by the University of Alaska Fairbanks has uncovered evidence suggesting that ancient Native Americans in present-day central Alaska began freshwater fishing around 13,000 years ago during the last ice age.

The study sheds light on how early humans adapted to changing landscapes and provides insights for modern populations facing similar challenges.

Published recently in the journal Science Advances, the study reveals that inhabitants of Interior Alaska between 13,000 and 11,500 years ago relied on freshwater fish, such as burbot, whitefish, and pike, as a food source.

This finding builds upon previous research by the University of Alaska Fairbanks, which had documented salmon fishing by the same ancient population.

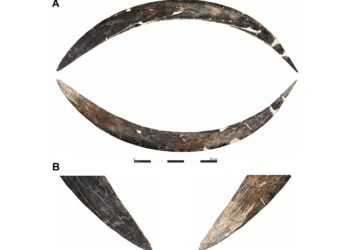

The research team conducted a comprehensive review of archaeological sites in Interior Alaska that were 7,000 years old or older. They discovered fish bones at seven sites and analyzed their age and species.

The bones were primarily found within homes and hearths, indicating their association with base camps rather than short-term hunting camps.

Furthermore, they were located far from lakes and streams, making it unlikely that predators had transported them. The absence of fishhooks or spears at the sites suggests that these early Alaskans likely employed nets and potentially weirs to catch fish.

By combining DNA and isotope analyses, the researchers identified four main fish taxa—salmon, burbot, whitefish, and northern pike—dating back to approximately 13,000 to 11,800 years ago.

These findings, along with the well-documented fishing records of local Native Alaskans, suggest that the adoption of fishing as a response to environmental change during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition played a significant role in the expansion of dietary choices.

Ben Potter, co-lead author of the paper and a professor of anthropology at UAF, emphasizes the significance of this finding, stating, “This is a compelling, evidence-based case for freshwater fishing at the end of the last Ice Age.”

The researchers believe that the adoption of freshwater fishing by early Native Americans in Alaska was a response to changing climatic conditions.

Prior to the Younger Dryas period, which commenced around 13,000 years ago, waterfowl were a more substantial part of the diet, supplementing large game hunting.

However, as temperatures dropped during the Younger Dryas, the reliance on waterfowl diminished, possibly due to the changing climate. In response, the ancient Alaskans adapted by incorporating freshwater fish species and new fishing technologies into their subsistence strategies. Burbot, in particular, played a crucial role, as it could be caught during late winter and early spring, when food resources were scarce.

The study’s findings have strong ties to modern subsistence activities among Indigenous peoples in Alaska. The researchers note that the use of fish as a resource spans millennia and continues to the present day. The discovery highlights the enduring cultural significance of fishing practices among Native communities.

The origins and development of fishing in North America have been poorly understood, and this study provides crucial insights into early inland fishing in the region. By adapting to changing climatic conditions, these early populations incorporated fish into their diets, setting a pattern that would later be expanded upon in the Holocene.

The study not only sheds light on ancient subsistence strategies but also underscores the enduring cultural and ecological significance of fishing among Indigenous peoples in Alaska.