A recent chemical analysis of two pieces of birch tar discovered in Germany indicates that Neanderthals possessed more sophisticated methods for producing adhesives than previously believed.

Researchers from the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen and their colleagues in Germany conducted a detailed examination of the birch tar that was utilized to attach Neanderthal tools. Their findings, published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, reveal a much more intricate process of creating the adhesive than was previously recognized.

The team compared various techniques for producing birch tar to the chemical residues present on ancient Neanderthal tools.

One aspect of human intelligence is our capacity to create synthetic substances and materials that do not naturally occur.

Previously, the use of tools was considered a distinguishing characteristic of human intelligence. However, as we have discovered that several animals also alter and manipulate materials for tool use, it has become a less exclusive indicator of intelligent behavior.

Nonetheless, the ability to manufacture synthetic materials remains a significant aspect of our cognitive advantage over other animals. This process necessitates conscious thinking, planning, and understanding of our actions to transform raw materials through a learned procedure.

The study conducted in Tübingen highlights that modern humans are not alone in possessing this ability, and they were not the first to achieve this mental milestone. The utilization of birch tar by Neanderthals predates any known use by modern humans by 100,000 years.

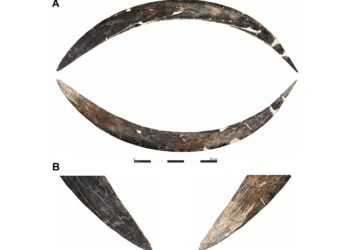

This sticky substance was employed as an adhesive to attach stone, bone, and wood in Neanderthal tools and weapons. Previously, it was suggested that Neanderthals may have collected birch tar by scraping it from rocks after a fire.

By conducting a comparative chemical analysis of two pieces of birch tar found in Germany, along with a substantial collection of reference birch tar created using Stone Age techniques, the researchers discovered that Neanderthals did not simply stumble upon birch tar after a fire, nor did they employ the most straightforward manufacturing method.

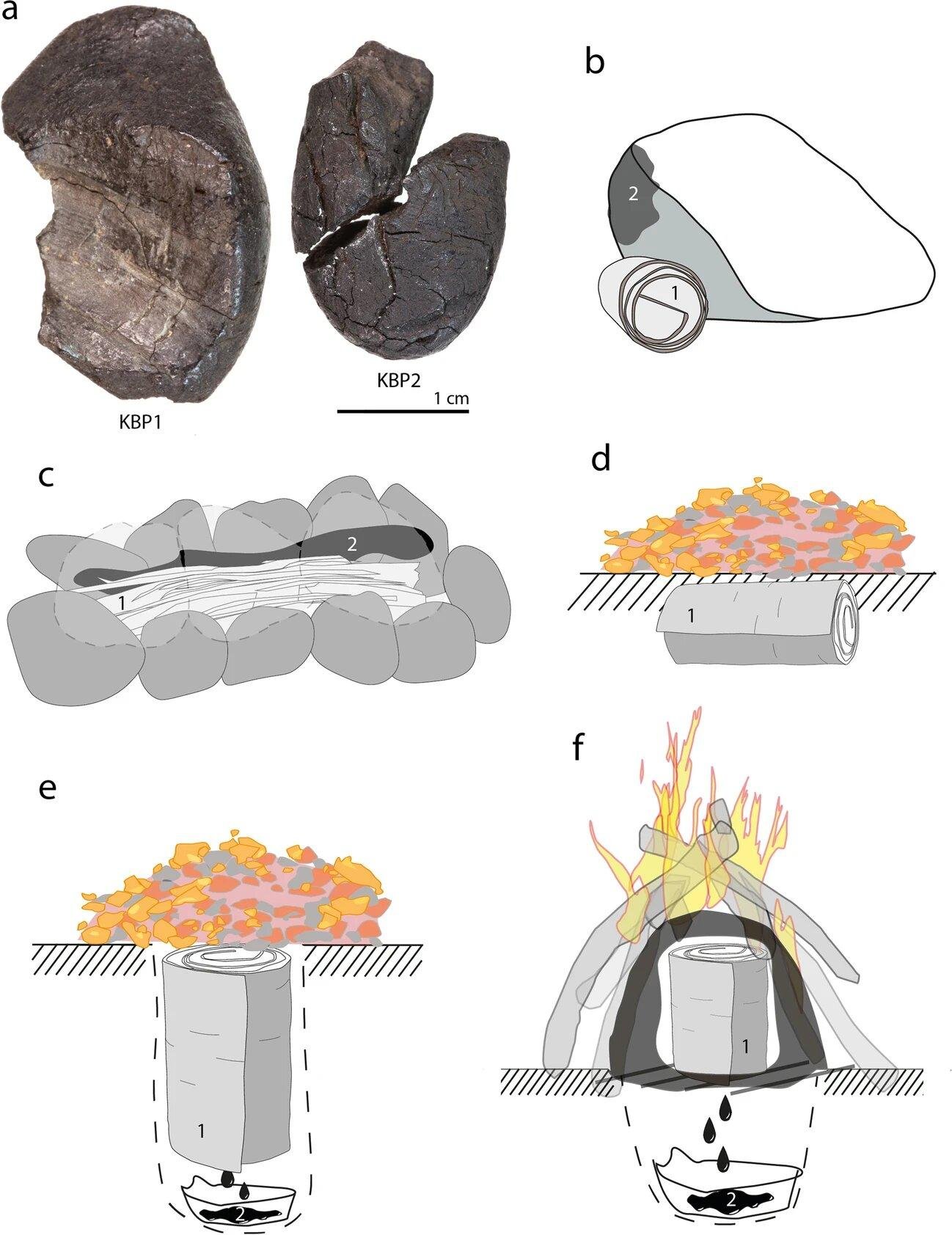

The researchers conducted experiments to replicate Neanderthal birch tar using five possible techniques. Two of these techniques were carried out aboveground, while the other two were tested underground.

The availability of oxygen during the extraction process left a distinct indicator on the experimental tar samples, creating a unique signature that clearly differentiated between above-ground and below-ground methods.

The absence of oxygen and carbon residues associated with soot in the modern samples indicated that the ancient Neanderthal tar had been produced underground.

The researchers emphasized that the underground techniques necessitated a more precise setup, as adjustments could not be made once the procedure was initiated.

The authors suggest that the level of complexity observed in the Neanderthal birch tar-making process is unlikely to have emerged spontaneously.

They propose that the technique would have originated from simpler methods and gradually evolved into a more intricate process through experimentation.

According to the authors, the production of birch tar by Neanderthals represents the earliest documented occurrence of this kind of advanced manufacturing in human evolution.