Researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History have identified nine cut marks on a 1.45 million-year-old left shin bone from a relative of Homo sapiens found in northern Kenya.

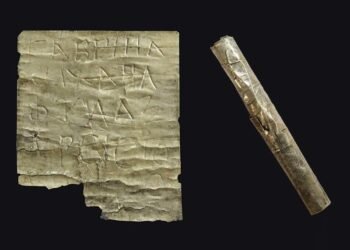

The researchers used 3D models of the fossil’s surface to analyze the cut marks and determined that they closely resemble the damage caused by stone tools. This finding provides the oldest and most specific evidence of hominins butchering and potentially consuming other hominins.

It suggests that the consumption of one’s own species for survival occurred further back in history than previously recognized.

Pobiner first encountered the fossilized tibia while examining the collections of the National Museums of Kenya’s Nairobi National Museum. She was searching for clues about prehistoric predators that may have hunted and eaten our ancient relatives but instead discovered what appeared to be evidence of butchery.

To confirm her suspicions, Pobiner sent molds of the cuts to Michael Pante of Colorado State University, who specializes in analyzing tooth, butchery, and trample marks.

The analysis revealed that nine of the 11 marks on the molds matched the damage caused by stone tools. The remaining two marks were likely bite marks from a big cat, possibly a saber-toothed lion.

The location of the cut marks on the shin bone, where a calf muscle would have attached, indicates that the intention was to remove flesh for consumption. Additionally, the uniform orientation of the cut marks suggests that they were made by a hand wielding a stone tool in a continuous sequence without changing grip or angle of attack.

Although the cut marks alone cannot definitively prove cannibalism, Pobiner believes it is the most likely scenario. She clarifies that cannibalism requires the eater and the eaten to be of the same species, and without enough evidence to identify the species of the bone’s owner, the determination cannot be made.

However, the similarity of the cut marks to those found on animal fossils processed for consumption supports the hypothesis that the leg bone was consumed for nutrition rather than ritual purposes.

The fossil shin bone was initially identified as Australopithecus boisei and later as Homo erectus. However, experts now agree that there is insufficient information to assign the specimen to a specific hominin species.

The use of stone tools does not narrow down the potential species responsible for the butchery. Recent research by Rick Potts, the National Museum of Natural History’s Peter Buck Chair of Human Origins, challenges the assumption that only the Homo genus used stone tools.

The order of events surrounding the fossil remains uncertain. The lack of overlap between the stone-tool cut marks and the bite marks makes it difficult to determine whether a big cat scavenged the remains after hominins had consumed most of the meat, or if the big cat killed a hominin before being chased away.

Further investigation and examination of other fossils, such as a skull found in South Africa in 1976, could shed more light on the earliest instances of hominin butchery.

Pobiner emphasizes the importance of revisiting museum collections and conducting collaborative research to expand our knowledge.

The discoveries made by reevaluating existing fossils demonstrate the value of examining specimens from different perspectives and utilizing various techniques to uncover new insights about our world. The team published their findings in a study in Scientific Reports.