Archaeologists from the Templo Mayor Project and Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have uncovered a stone chest, known in Nahuatl as a tepetlacalli, containing a ritual offering of 15 anthropomorphic figurines at the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

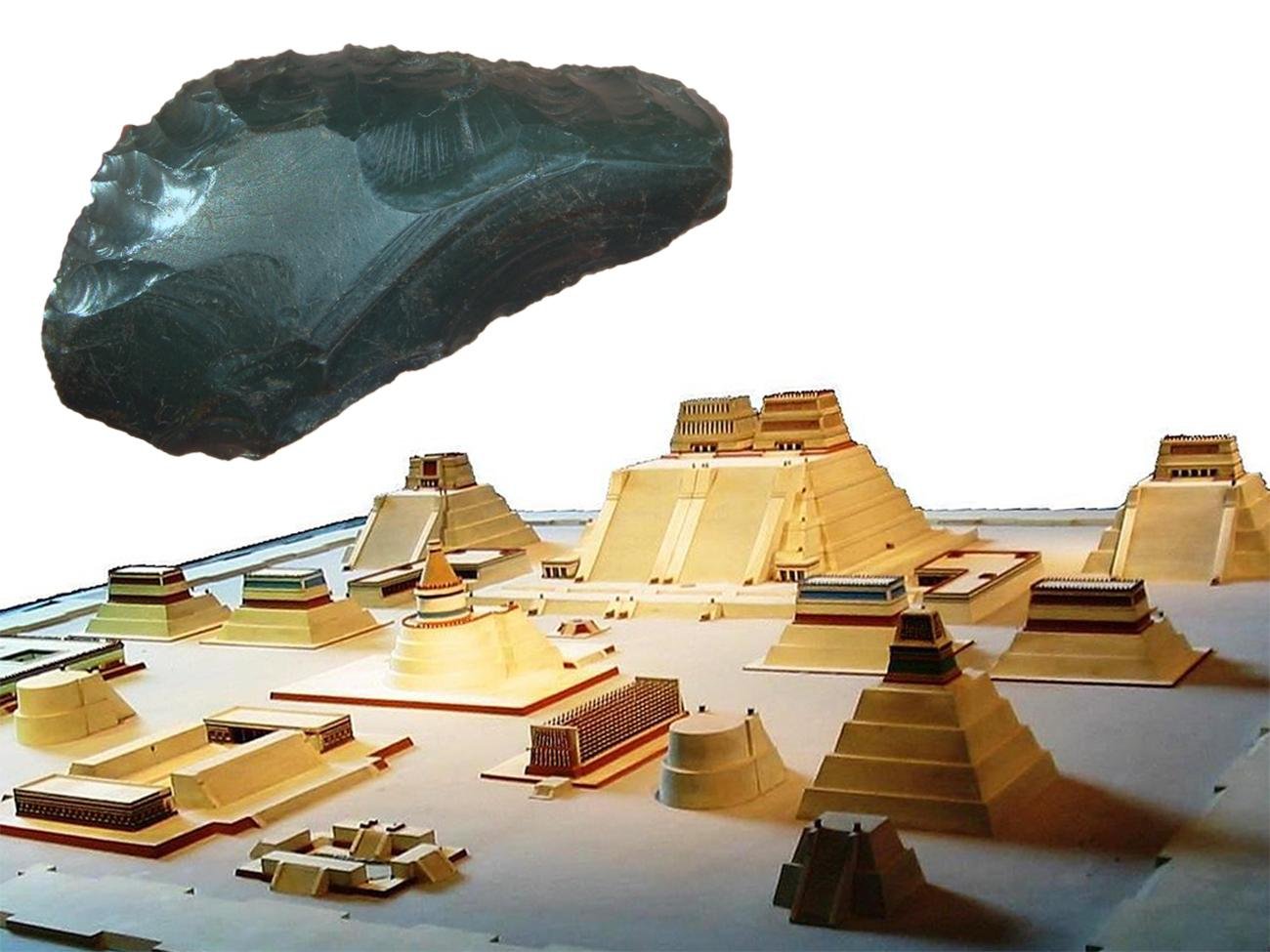

The Templo Mayor, once the central temple of Tenochtitlan—the Aztec Empire’s capital—was dedicated to two principal deities: Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, and Tlaloc, the god of rain and agriculture. Its construction began shortly after CE 1325, but the temple was destroyed in 1521 following the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlan.

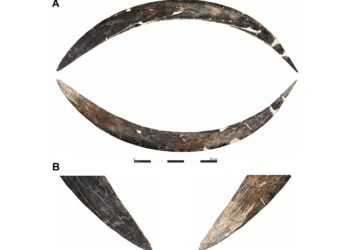

The figurines found inside the stone chest are carved in the Mezcala style, which is recognized for its abstract and geometric features, even in the representation of human faces. The Mezcala culture thrived in the area now known as northern Guerrero in southwestern Mexico and dates back to the Preclassic period (700–200 BCE) and the Classic period (250–650 CE).

The Aztecs developed a fascination with Mezcala artifacts and incorporated them into their own cultural and religious framework. During the reign of Emperor Moctezuma I (1440–1469 CE), the Aztec Empire expanded significantly, and Mezcala relics—some more than a thousand years old—were deliberately excavated and retrieved from ancient sites.

Designated Offering 186, the stone chest contained 14 male anthropomorphic figurines and one miniature female figure. Made from green metamorphic stone, the figurines range in height from nearly a foot to just an inch. One figurine still bears remnants of facial paint representing Tlaloc, indicating that these ancient objects were consciously integrated into the Aztecs’ own religious rites.

The chest was located beneath the platform at the rear façade of the Templo Mayor, in a stratigraphic layer associated with the reign of Moctezuma I. In addition to the figurines, the chest held two earrings shaped like rattlesnakes, 135 greenstone beads, and a collection of 1,942 seashells, snail shells, and pieces of coral.

These marine materials came from the Atlantic coast, an area conquered by the Aztecs of the Triple Alliance—formed by Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan—during the rule of Moctezuma I.

The discovery illustrates the Mexica people’s deep respect for symbolism and ritualistic offerings. According to archaeologist Leonardo López Luján, director of the Templo Mayor Project, the stone chest served as a sacred container for some of the most important emblems of water and fertility.

Just as the Mexica stored valued possessions such as jewelry, fine feathers, and cotton garments in palm-frond chests in their homes, they used these stone chests to house sacred items like sculptures, greenstone beads, shells, and snails.