Chinese archaeologists have unearthed the first-ever complete skeleton of a giant panda within the burial site of a remarkable Han dynasty emperor dating back over two millennia.

The panda’s remains were meticulously positioned within a satellite pit, and oriented with its head directed towards the principal tomb of Emperor Wen, a prominent ruler of the Western Han dynasty whose reign spanned from 180 to 157 BCE.

The monumental discovery was made by a team of researchers from the Shaanxi Academy of Archaeology, led by archaeologist Hu Songmei. This marks the first instance of a fully intact giant panda skeleton being found within an ancient burial complex, a fact that underscores the historical significance of the find.

Emperor Wen’s tomb is situated in the vicinity of Xi’an, a city located in Shaanxi province that once served as the capital of China and now stands as the capital of Shaanxi province.

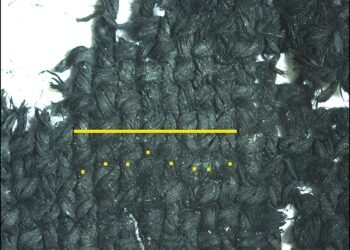

During the course of their exploration, the archaeologists uncovered more than 380 rectangular earth pits housing an array of animal skeletons. This diverse collection of remains included various mammals interred in brick burial receptacles, as well as reptiles within wooden coffins and avian specimens nestled within pottery receptacles.

The wide variety of wildlife sacrifices found within the tomb’s vicinity is believed to symbolize the elevated status of the Han rulers. While animal sacrifices were also present in tombs of commoners, these were typically restricted to domesticated animals such as dogs and pigs.

Notably, exotic creatures and rare birds were exclusively unearthed within the mausoleums of emperors, empresses, and emperors’ mothers, emphasizing their role as symbols of prestige and honor.

“The animal sacrifice pits that we excavated this time could be a replica of the royal gardens and farms in Western Han dynasty,” said Hu Songmei, the lead archaeologist.

Among the remarkable finds alongside the giant panda, the archaeologists identified the complete skeleton of a Malaysian tapir, a species that vanished from China around a millennium ago and is currently classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The presence of the tapir and the giant panda raises questions about the biodiversity of ancient China and the potential coexistence of these species within the region.

Hu Songmei further elaborated on the potential ecological conditions of the time, suggesting that the appearance of the panda near Xi’an could indicate a warmer climate, allowing bamboo to flourish in areas that are not part of their current natural habitats. “The northern slopes of Qinling Mountains had wetter and hotter forests, and the temperature at that time should be one or two degrees Celsius higher than now,” Hu explained.

Additionally, the tomb’s contents featured an assortment of other captivating creatures, including tigers, yaks, a gayal bull indigenous to South Asia, and a Himalayan takin. The remains of a rhino and a golden eagle were also discovered within the tomb belonging to Empress Dowager Bo, the mother of Emperor Wen.

To gain further information about the dietary habits and origins of these animals, the archaeologists intend to conduct DNA and isotope analyses. These analyses will provide valuable information about the animals’ diets and geographic locations during the ancient Han dynasty.

Emperor Wen, known by his birth name Liu Heng, reigned over a period of economic prosperity and population expansion within the Han dynasty. The find of the giant panda and other creatures within his tomb serves as a testament to the complexity of cultural practices and symbolic representations during his reign.

Previously archaeologists found a previously unknown species of gibbon within the burial site of Lady Xia, who was the grandmother of Qin Shihuang, China’s first emperor.