A recent study conducted by Mainz anthropologists and an international team of archaeologists sheds light on the origins and genetic structure of prehistoric family communities.

Jens Blöcher and Joachim Burger from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) led this research, which involved the analysis of genomes extracted from skeletons belonging to an extended family within a Bronze Age necropolis situated in the Russian steppe.

This 3,800-year-old site, known as the Nepluyevsky burial mound, represents an archaeological treasure located on the border between Europe and Asia. Employing statistical genomics, the scientists successfully decoded the complex family and marriage relationships that characterized this ancient society.

The collaborative study involved archaeologists from Ekaterinburg and Frankfurt A.M. and has been documented in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The focal point of their investigation was a kurgan, a burial mound, that served as the final resting place for six brothers, along with their wives, children, and grandchildren.

Among these brothers, the eldest exhibited a distinctive familial status, as he had fathered eight children with two different wives, one of whom hailed from the Asian steppe regions in the east. In contrast, the other brothers displayed no indications of polygamy and likely led monogamous lives, raising significantly fewer offspring.

As lead author Jens Blöcher noted, “It is remarkable that the first-born brother apparently had a higher status and thus greater chances of reproduction. The right of the male firstborn seems familiar to us, it is known from the Old Testament, for example, but also from the aristocracy in historical Europe.”

However, the genomic analysis has yielded even more intriguing findings. Many of the women interred within the kurgan were immigrants, suggesting a pattern of female marriage mobility. This practice, grounded in economic and evolutionary considerations, involved women from external regions marrying into the family to prevent inbreeding while ensuring the continuity of the family line and property by the male members who remained local.

Consequently, the genomic diversity among the prehistoric women exceeded that of the men. These women, originating from various locales, were not genetically related to one another but were united by their commitment to follow their husbands into the afterlife.

This evidence suggests a combination of “patrilineality” and “patrilocality” in Nepluyevsky, implying the transmission of local traditions through the male line and the concept that a family’s residence is where its male members live.

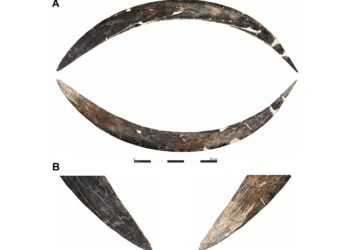

“Archaeology shows that 3,800 years ago, the population in the southern Trans-Ural knew cattle breeding and metalworking and subsisted mainly on dairy and meat products,” says Svetlana Sharapova, archaeologist from Ekaterinburg and head of the excavation.

Unfortunately, the state of health of this community appears to have been poor, with an average life expectancy of 28 years for women and 36 years for men. The kurgan’s usage abruptly shifted in the last generation, with an almost exclusive presence of infants and young children. This puzzling change has led archaeologists to speculate that either disease decimated the inhabitants or that the surviving population sought a better life elsewhere.

The genomic evidence also suggests that populations genetically akin to the Nepluyevsky society existed across the vast Eurasian steppe region. This research opens doors for future investigations into whether the “Nepluyevsky” model applies to other prehistoric sites in Eurasia.