Art and archaeology converge in an exciting discovery as researchers from Dartmouth and the University of Cambridge uncover the earliest artistic representation of an Acheulean handaxe.

This historical revelation, found within the “Melun Diptych” painted by Jean Fouquet around 1455, provides a unique glimpse into the ancient world of these stone tools, shedding light on their social and cultural significance.

The “Melun Diptych,” a 15th-century religious painting commissioned by Étienne Chevalier, treasurer for King Charles VII of France, has been the subject of art historical study for years. The left panel of the diptych portrays Chevalier and his patron saint, St. Stephen, holding a book with an intriguing, jagged stone resting upon it. Art historians previously interpreted the stone as a representation of St. Stephen’s martyrdom by stoning.

The unexpected twist in this tale came when a team of researchers, including Steven Kangas, a senior lecturer in the Department of Art History at Dartmouth, attended a seminar in 2021. The talk, led by Montgomery Fellow Charles Musiba, an expert on human origins in Tanzania and South Africa, piqued their interest due to the handaxe-rich Isimila site in Tanzania.

Handaxes have been recognized as tools used by ancient human ancestors for over 1.6 million years, primarily associated with Homo erectus. However, the history of human understanding of these artifacts remains enigmatic. Prior to the Enlightenment, they were often considered “thunderstones” believed to have fallen from the sky during lightning storms.

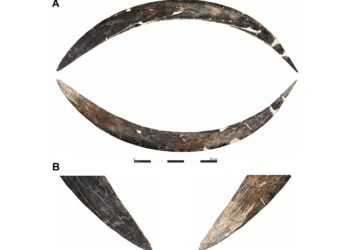

The “Melun Diptych” painting presented a fresh opportunity to investigate this history further. The researchers employed various analyses, including Elliptical Fourier Analysis, shape comparison, and examination of flake scars on the painted stone object, to determine its origin and significance.

The team’s findings are compelling. The shape of the stone in the painting closely matches Acheulean handaxes found in the region where Fouquet lived, with a 95% similarity in shape. In addition, its coloration, featuring yellow, brown, and red hues, mirrors the weathering patterns of actual stone handaxes, often crafted from flint or silica-rich rocks.

These remarkable insights point to the intriguing possibility that the handaxe depicted in the 15th-century painting might be an actual Acheulean handaxe, created by an earlier society. It suggests that these tools might have been more prevalent and known in society than previously thought.

Three theories arise regarding its inclusion in the artwork: these objects could have been common in medieval Northern France, or perhaps they were rare and reserved for the upper class, or they could have held specific religious or cultural significance.

While the research cannot definitively claim that Fouquet painted an Acheulean handaxe, the evidence strongly supports this notion, pushing back the timeline for the social history of handaxes to the mid-15th century, well before other documented instances.