Scientists have uncovered the vital role played by “biocrusts” in preserving and fortifying sections of the Great Wall of China against the relentless forces of erosion.

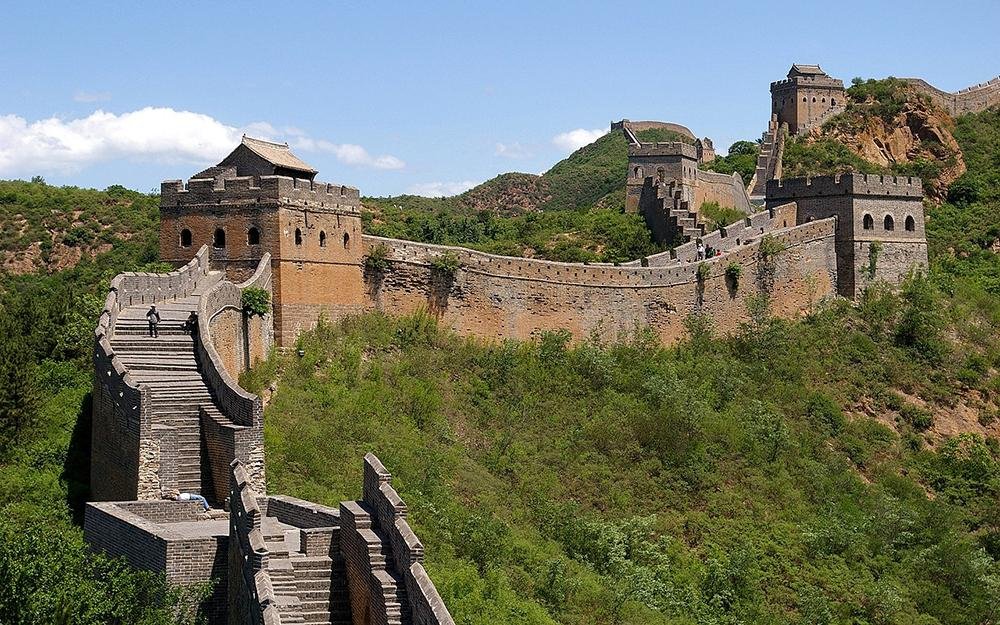

Stretching over 13,000 miles and constructed over centuries, this iconic cultural landmark faced potential deterioration due to natural erosion, prompting a comprehensive study by a team of international soil and water ecosystem conservation specialists.Ancient builders, seeking stability, utilized rammed earth—a mix of organic materials like soil and gravel—in constructing the Great Wall.

The researchers, led by Professor Bo Xiao from China Agricultural University’s College of Land Science and Technology, discovered that these organic components laid the foundation for the growth of biocrusts, which consist of cyanobacteria, mosses, and lichens. Contrary to the assumption that biocrusts hasten erosion, the study revealed their role as protectors, creating a living shield against wind, water, and temperature fluctuations.

The team collected samples from eight sections of the Ming-era wall, built between 1368 CE and 1644 CE, during the Ming Dynasty. The study, published in the journal Science Advances, demonstrated that a remarkable 67% of these samples contained biocrusts. These “ecosystem engineers,” as termed by Xiao, were found to enhance the mechanical strength of the wall significantly.

To gauge the strength and integrity of the wall, researchers employed portable mechanical instruments both on-site and in the laboratory.

The biocrust-covered samples exhibited remarkable stability, sometimes up to three times stronger than plain rammed earth samples. Moss-dominated biocrusts, particularly prevalent in wetter, semi-arid environments, emerged as the most effective in enhancing the wall’s strength and stability, reducing erodibility.

Professor Xiao clarified, “These cementitious substances, biological filaments, and soil aggregates within the biocrust layer finally form a cohesive network with strong mechanical strength and stability against external erosion.” The study challenges previous speculation that biocrusts may accelerate the deterioration of historic structures, offering a new perspective on their conservation role.

Built over several centuries, starting around 221 BCE, the Great Wall served as a formidable defense system for China’s northern border. While natural erosion threatened its longevity, the symbiotic relationship between rammed earth, biocrusts, and the ingenious planning of ancient builders has proven crucial in preserving this architectural marvel.

The research not only unveils the protective function of biocrusts on the Great Wall but also provides insights into potential conservation strategies for other heritage structures built using rammed earth. In a broader context, this discovery parallels a study in Honduras by a team from the University of Granada, which found that organic plant materials added by early Mayan people reduced weathering of stone structures.

While the biocrusts act as formidable protectors against environmental elements, it is crucial to note the ongoing threats posed by human activities.