Babylon’s iconic Ishtar Gate, a brilliant blue glazed-brick structure commissioned by King Nebuchadnezzar II, has long been shrouded in mystery regarding its construction timeline. A recent study, titled “An archaeomagnetic study of the Ishtar Gate, Babylon,” published in the journal PLOS One, sheds light on the historical puzzle by employing advanced techniques to measure geomagnetic fields preserved in clay bricks.

Previous beliefs tied the construction of the Ishtar Gate to the celebration of the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem. However, a comprehensive analysis challenges this notion, suggesting that the gate’s purpose may have been different than initially thought. The gate, featuring wild bulls and mušhuššu-dragons, was erected in three phases and served as the entrance to the ancient city of Babylon in southern Mesopotamia.

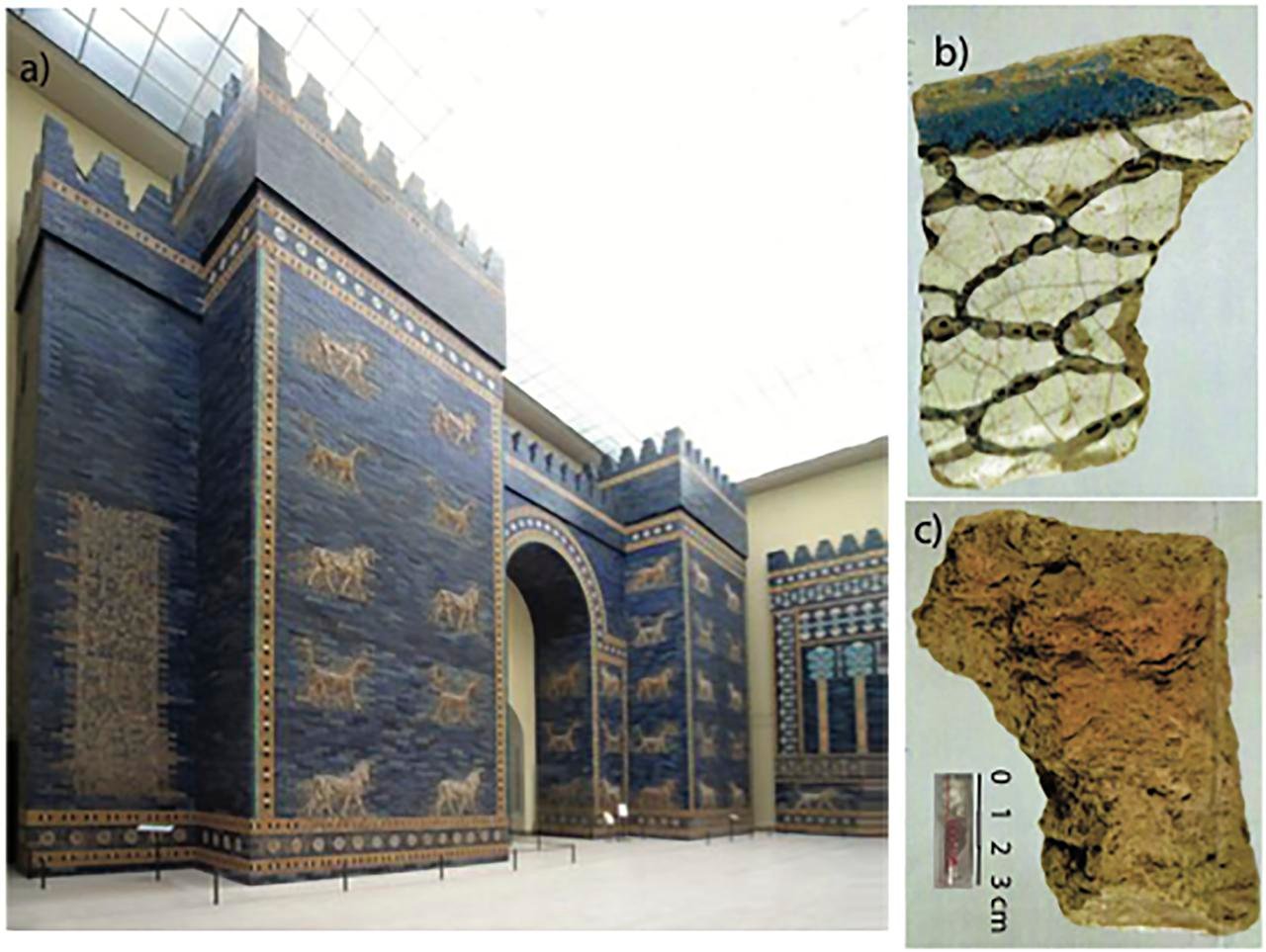

Archaeologists faced uncertainties about the timeline of construction phases following Nebuchadnezzar II’s initial order. Some researchers even questioned if the king had died before the gate’s completion. To resolve these uncertainties, the research team collected tiny samples from five fired mud bricks representing the three construction phases of the Ishtar Gate, now housed at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Utilizing archaeomagnetism, a method that measures the preserved geomagnetic fields in archaeological objects, the team aimed to establish a more precise construction timeframe than traditional radiocarbon dating. This analysis revealed that there were no substantial chronological gaps between the construction phases, providing a unified construction period around 583 BCE.

As the authors write in their paper, “The gate complex was constructed some time after the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem in 586 BCE, and there were no substantial chronological gaps in the construction of each consecutive phase.” The researchers emphasized that the magnetic field measurements in the bricks were consistent, indicating a cohesive construction process during Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign.

Contrary to previous speculations, the study challenges the idea that the Ishtar Gate’s style evolved during construction. Instead, it suggests that phases II and III are integral to the original design, reflecting the construction process rather than later additions detached from the initial phase.

Standing at a height exceeding 38 feet, the Ishtar Gate derives its name from the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. Its facade is embellished with alternating rows of dragons and bulls, showcasing a combination of glazed bricks in yellow and brown tiles, encased by blue bricks thought to be crafted from lapis lazuli. Functioning as the majestic entrance to the city, this remarkable gate held a distinguished place on the original roster of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The study’s findings not only provide clarity about the Ishtar Gate’s construction timeline but also open avenues for further archaeomagnetic analyses on other ancient structures in Mesopotamia. Fired mud bricks, common in that era, have proven to be reliable sources for archaeomagnetic studies. Researchers aim to expand their investigations to enhance the understanding of ancient structures in southern Mesopotamia.