Archaeologists have delved into the mysterious burial practices of early Bronze Age communities in western Eurasia, shedding light on the family relationships and cultural dynamics of the Bell Beaker people from 3000-2000 BCE.

An international study led by researchers from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz and the University of Ferrara, among other European institutions, has re-examined two remarkably similar double burial sites, one in Altwies, Luxembourg, and another in Dunstable Downs, England.

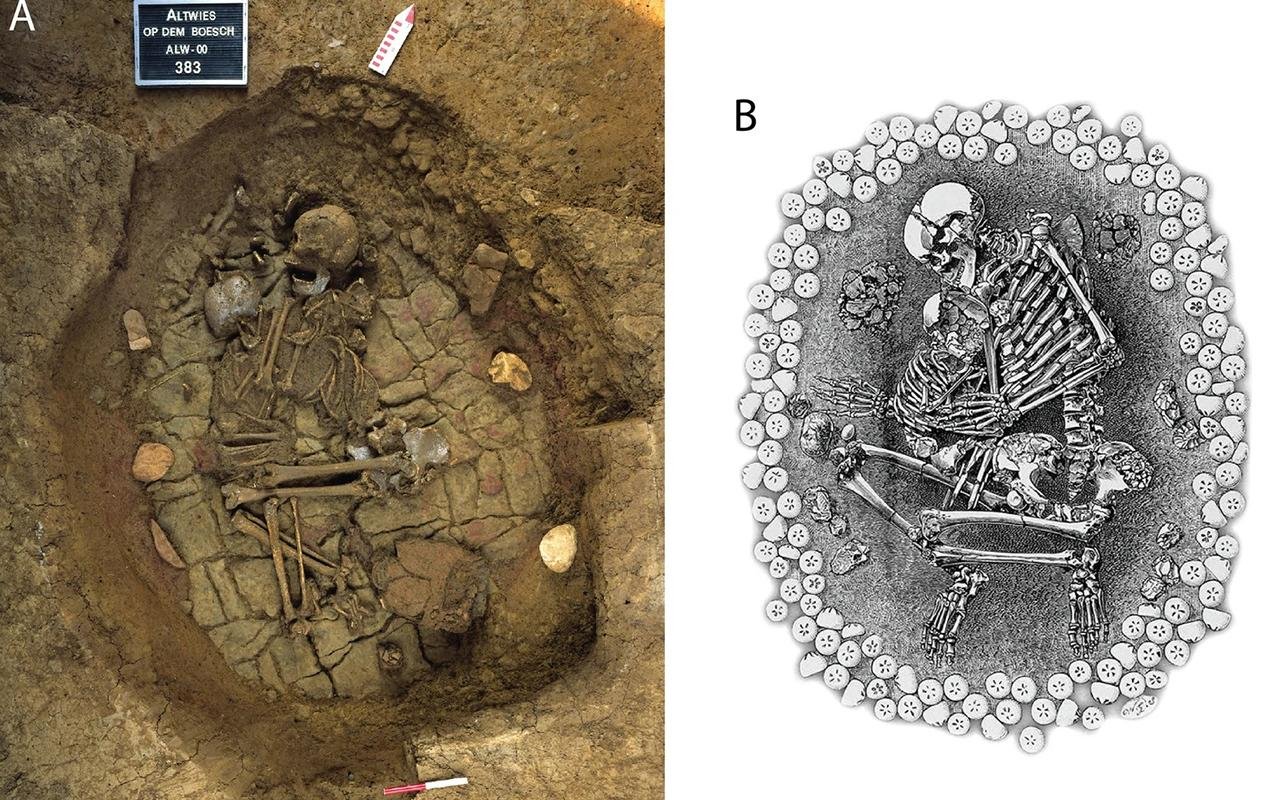

In Altwies, a burial site discovered in 2000 during a construction project revealed the skeletons of a woman and a 3-year-old boy facing each other, with the woman holding the boy’s head in her hand. Meanwhile, the site in Dunstable Downs, England, uncovered in 1887, featured a young woman buried with a 6-year-old girl, identified as paternal aunt and niece through DNA analysis, challenging expectations of a mother-daughter relationship.

Dr. Nicoletta Zedda from the University of Ferrara, a lead author of the study, explained, “The skeletons from Altwies were of a woman and a boy of around three years of age, and DNA analysis revealed that they were indeed mother and son. The picture looks different for Dunstable Downs: a young woman and a girl about 6 years old, but DNA revealed they are, in fact, paternal aunt and niece.”

The research, published in Scientific Reports, presented genetic evidence suggesting a patrilineal descent system for Bell Beaker communities in western Eurasia. The study involved a multidisciplinary analysis, incorporating archaeology, anthropology, and ancient DNA techniques, revealing shared ancestry and cultural connections among the early European farmers.

Dr. Maxime Brami of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, one of the lead authors, explained: “The data might hint at a patrilineal descent system for Western Eurasian Bell Beaker people. Our findings suggest that, at least in some Early Bronze Age communities, extended families lived and buried their dead together, placing emphasis on biological and kin relationships.”

The orientation of Bell Beaker graves in continental Europe followed strict rules based on the individual’s sex. In Altwies, the orientation of the grave matched the child’s sex, while at Dunstable Downs, the adult and child were second-degree relatives on the paternal side, indicating a potential substitute parent or primary caregiver role played by the paternal aunt.

Despite the geographical separation of over 500 kilometers between the Luxembourg and England burial sites, the study uncovered over a hundred joint burials across Eurasia from the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE. The widespread occurrence of the practice suggested a commonality in mourning rituals among Bell Beaker communities, perhaps indicative of shared cultural traditions.

While the direct causes of the individuals’ deaths remain unknown, the study proposed possibilities such as violence, infections, or pandemics. However, the consistency in the ritual treatment and positioning of bodies in burial highlighted the deep symbolic significance adhered to across different regions.

“The body of a woman, lying as though sleeping, clasping a child in her arms, is poignant and emotive. Although that peaceful image may be deceptive, it still reflects a lost meaning retained across thousands of miles and amongst many diverse cultures,” remarked Dr. Brami.

The research project not only unraveled the complexities of family relationships and burial customs but also showcased the interconnectedness of Bell Beaker communities in western Eurasia during the Bronze Age.