In a new study published in the journal Science Advances, researchers have unveiled compelling evidence that pagan tribes in the Baltic region imported horses from Christianized Scandinavia for sacrificial rituals during the late medieval period.

Historically, horse sacrifices were a prominent feature of funerary rituals across Europe from prehistoric times through the medieval period. The practice was particularly persistent among the eastern Baltic tribes, where it continued until the 13th and 14th centuries. Archaeological findings have frequently uncovered horse remains in burial sites, often in separate pits or alongside human cremations.

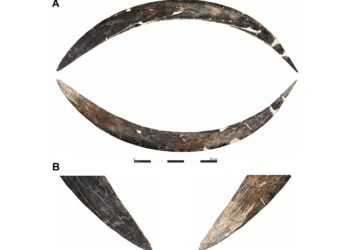

An international team of researchers conducted a detailed analysis of more than 70 horse teeth from nine burial sites across modern-day Poland, Lithuania, and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, dating from the 1st to 13th centuries. They utilized a technique called strontium isotope analysis, which can trace the geographic origins of animal remains.

This method revealed that some horses originated from regions as far as modern Sweden or Finland, indicating that they had traversed the Baltic Sea, covering distances of 300 to 1,500 kilometers (roughly 186 to 932 miles).

“Our results prove that horses were crossing the Baltic Sea on ships, a level of mobility not previously recognized archaeologically,” the study authors wrote. This discovery disrupts the previously held belief that pagan Baltic tribes exclusively used locally bred horses for sacrifices.

Previous assumptions within Baltic archaeology posited that stallions were exclusively chosen for these public sacrifices, which were believed to be conducted at the funerals of elite male warriors. However, the genetic and isotopic analyses conducted in this study reveal a more complex picture. Approximately 66% of the horses were identified as stallions, while 34% were mares.

Lead author Katherine French, formerly of Cardiff University’s School of History, Archaeology, and Religion and now based at Washington State University, said: “This research dismantles previous theories that locally-procured stallions were exclusively selected for sacrifice. Given the unexpected prevalence of mares, we believe the prestige of the animal, coming from afar, was a more important factor in why they were chosen for this rite.” This suggests that the social and symbolic status of the horses, possibly enhanced by their long-distance origins, played a crucial role in their selection for sacrifice.

Co-author Richard Madgwick, also from Cardiff University’s School of History, Archaeology, and Religion, remarked on the broader implications of these findings. “Pagan Baltic tribes were clearly sourcing horses overseas from their Christian neighbors while simultaneously resisting converting to their religion. This revised understanding of horse sacrifice highlights the dynamic, complex relationship between pagan and Christian communities at that time,” Madgwick explained.

The research offers a nuanced view of the interactions between these communities, illustrating how pagan Baltic tribes engaged in long-distance trade and maintained cultural practices in the face of increasing Christian influence. This period saw significant trade networks stretching across the Baltic Sea, particularly with Sweden, which had established robust maritime connections by the 11th to 13th centuries. The presence of a Scandinavian-influenced artifact, such as a trader’s weight found with one of the non-local horses in Kaliningrad, suggests that these imported horses could have arrived with Scandinavian traders or owners who were integrated into Baltic society.

The findings show the importance of horses in Baltic pagan culture. Horses were not only a symbol of prestige and status but also a critical component of their funerary rites, which often involved elaborate and gruesome sacrifices. The animals were decapitated, flayed, quartered, or even buried alive, reflecting the significant resources and societal value attributed to these rites. The practice of horse sacrifice, deeply embedded in the pagan belief systems of the Balt tribes, gradually waned as Christianity spread through the region.

Dr. French and her team plan to continue their research to further explore the complex socio-economic and cultural interactions between these communities.