An international team of researchers, including faculty from Binghamton University, has documented the first case of Down syndrome in Neanderthals. This discovery suggests these ancient human relatives were capable of providing care and support for vulnerable members of their groups.

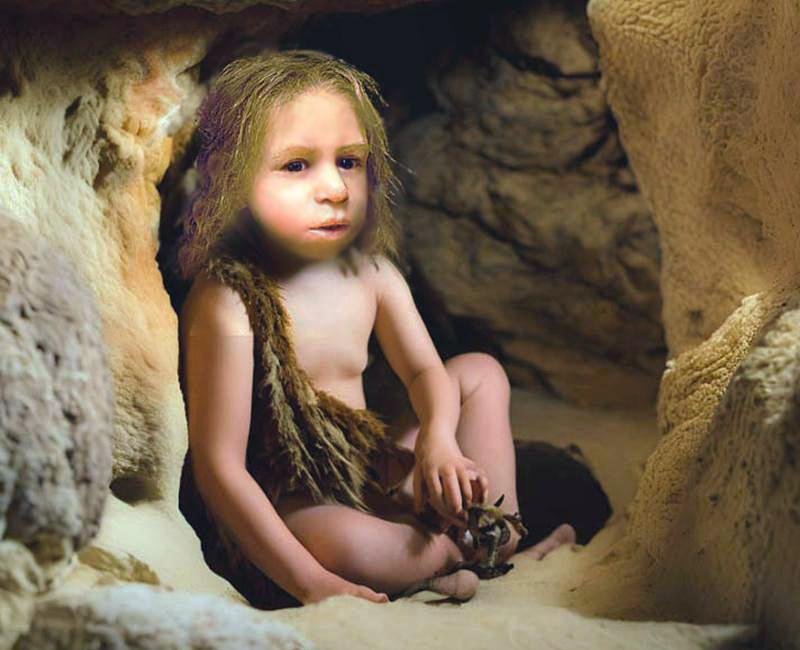

Led by anthropologists from the University of Alcalá and the University of Valencia in Spain, the research focused on the skeletal remains of a Neanderthal child, affectionately named “Tina,” found at Cova Negra, a cave in Valencia known for significant Neanderthal discoveries.

Led by anthropologists from the University of Alcalá and the University of Valencia in Spain, the research focused on the skeletal remains of a Neanderthal child, affectionately named “Tina,” found at Cova Negra, a cave in Valencia known for significant Neanderthal discoveries.

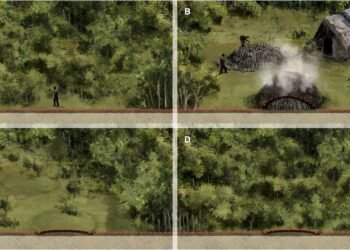

“The excavations at Cova Negra have been key to understanding the way of life of the Neanderthals along the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula,” said Professor Valentín Villaverde from the University of Valencia. “They have allowed us to define the occupations of the settlement: of short temporal duration and with a small number of individuals, alternating with the presence of carnivores.”

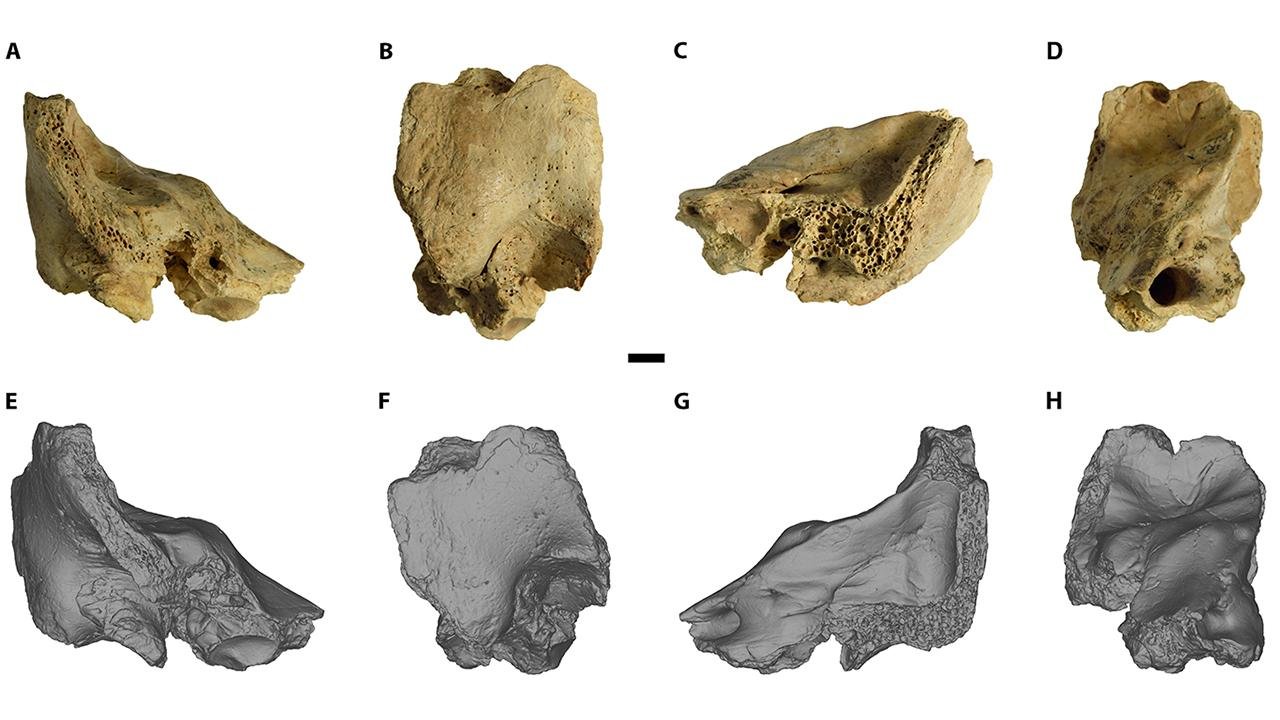

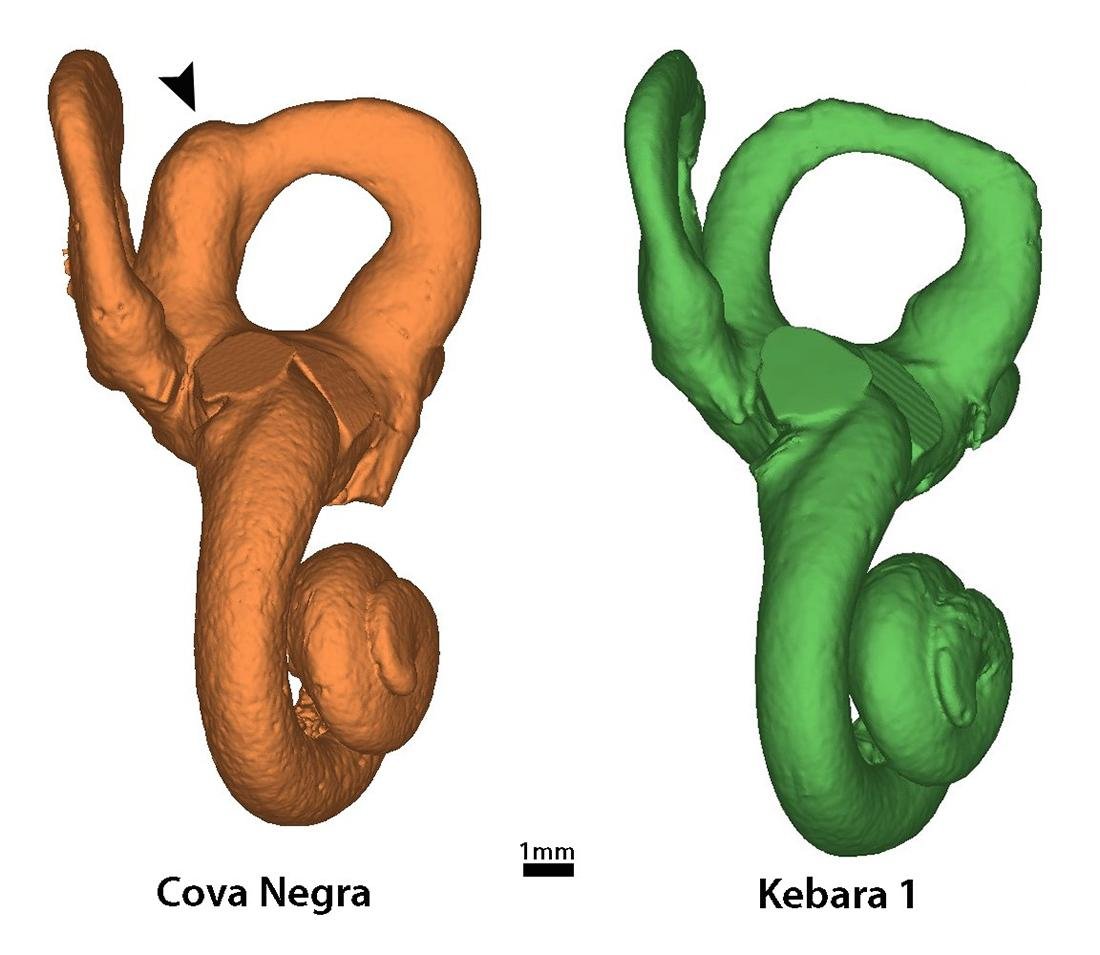

Using micro-computed tomography scans of a small cranial fragment from Tina’s right temporal bone, researchers reconstructed a three-dimensional model for detailed analysis. Tina suffered from a congenital pathology of the inner ear associated with Down syndrome, which resulted in severe hearing loss and disabling vertigo. Despite these challenges, Tina survived to at least six years old, indicating she received extensive care from her social group.

“This is a fantastic study, combining rigorous archaeological excavations, modern medical imaging techniques, and diagnostic criteria to document Down syndrome in a Neanderthal individual for the first time,” said Professor Rolf Quam, an anthropologist at Binghamton University. “The results have significant implications for our understanding of Neanderthal behavior.”

Neanderthals have long been known to care for disabled individuals, but previous cases involved adults, leading some scientists to suggest this care was part of a reciprocal exchange rather than true altruism. Tina’s case, however, provides evidence of care for an individual who could not return the favor, suggesting genuine altruistic behavior.

“What was not known until now was any case of an individual who had received help, even if they could not return the favor,” said Mercedes Conde-Valverde, professor at the University of Alcalá and lead author of the study. “That is precisely what the discovery of ‘Tina’ means.”

The study, published in Science Advances on June 26, 2024, highlights the sophisticated social behaviors of Neanderthals, challenging their often brutish image. The child’s survival for at least six years in a harsh Stone Age environment underscores the importance of community care and support.

The tiny fossil of Tina was excavated in 1989 from the Cova Negra archaeological site, but its significance was only recently understood during a review of faunal fragments. The peculiar proportions of its semicircular canals, characteristic of Neanderthals, helped identify it as a Neanderthal.

The research did not include precise dating of the bone, which would require extracting ancient DNA. However, Neanderthals occupied the site between 146,000 and 273,000 years ago. The team has not determined the sex of the young Neanderthal.

Today’s understanding of Down syndrome, a condition caused by an extra partial or full chromosome, shows that people with Down syndrome can lead long lives. Historically, survival into childhood was less common, even as recently as the early 20th century. Life expectancy for children with Down syndrome in 1929 was about nine years, increasing to 12 years by the 1940s. Today, in the United States, the life expectancy for individuals with Down syndrome exceeds 60 years, according to the National Down Syndrome Society.

Past studies of Neanderthal remains have suggested that they cared for vulnerable group members. For example, a Neanderthal man buried in Shanidar Cave in Iraq had severe disabilities but lived a long life, and the “Old Man of La Chapelle” in France showed signs of degenerative arthritis but received care from his group. These cases support the idea that Neanderthals practiced true altruism.

The case of Tina underscores the deep-rooted human instinct to care for those in need, regardless of their ability to reciprocate.