Recent excavations in Pompeii have uncovered a remarkable room with walls painted in a vivid, sky-blue hue, a color seldom seen in Pompeian ruins.

This room, discovered in the Insula 10 area of Regio IX, is thought to have served as a sacrarium, a space dedicated to pagan rituals and the preservation of sacred objects.

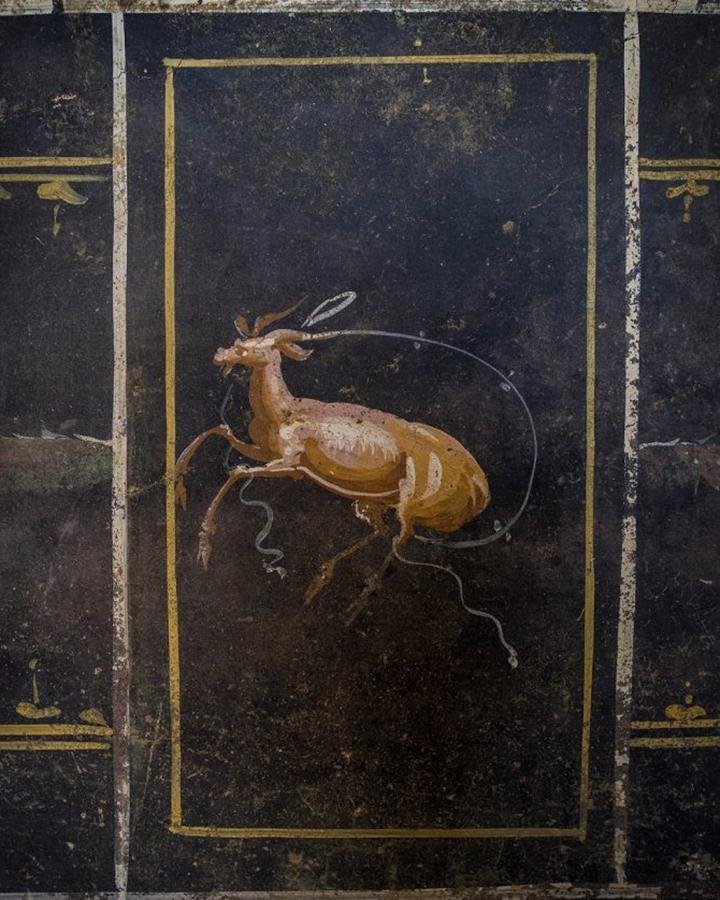

The walls of this 8-square-meter room, known as Room 32, are adorned with frescoes in the Fourth Style, characterized by its intricate and narrative aesthetic. This style, prevalent from around 60 to 79 CE, is noted for its architectural elements and elaborate scenes that adorned the walls of Roman houses.

The sacrarium’s walls are painted a brilliant sky blue, a color rarely seen in Pompeian frescoes and typically reserved for spaces of great significance. The blue backdrop is complemented by red-lined niches, where statues and other devotional objects likely stood.

The frescoes depict female figures representing the four seasons, agriculture, and shepherding. These figures are adorned with crowns of flowers, flowing garments, and in some cases, depicted without clothes, adding to the room’s mystical aura.

The excavation team found several artifacts within the room that suggest it was used for pagan rituals and the storage of sacred objects. Among the discoveries were 15 amphorae, two jugs, two lamps, and three decorative boxes embedded in the walls that likely held devotional statues. Building materials such as piles of oyster shells, intended to be mixed with plaster and mortar, indicate that the house was undergoing renovations at the time of the eruption.

Gennaro Sangiuliano, Italy’s Minister of Culture, visited the site and described the ancient city as “a treasure chest that is still partly unexplored.” He stated: “Pompeii is an immense archaeological laboratory that gained strength in recent years and amazes the world with continuous discoveries brought to light.”

This discovery aligns with the broader context of Roman literature and art, where the pastoral and agrarian themes often symbolized a nostalgic return to simpler times. Works like Virgil’s “Georgics” and “Eclogues” celebrated the rural idyll while acknowledging the tension between the idyllic past and the realities of contemporary Roman life. The room’s decorations may reflect this cultural ambivalence, embodying both reverence for agricultural deities and a longing for the lost simplicity of rural life.

Interestingly, the sacrarium contrasts sharply with another recent find in the nearby villa of Civita Giuliana, where archaeologists uncovered the starkly utilitarian quarters of servants. This space, devoid of decorative frescoes, contained a bed, work tools, a basket, rope, and wooden planks. These items were preserved by the volcanic ash, which solidified into a material known as cinerite. Researchers were able to recreate the original shapes of these objects by filling the voids left by the decayed organic material with plaster.

The contrast between the luxurious sacrarium and the humble servants’ quarters highlights the social stratification in ancient Pompeii. While the wealthy could afford to decorate their homes with intricate frescoes and conduct private religious rituals in dedicated spaces, the servants lived and worked in much more modest conditions.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

I’m wondering why the author felt the need to include the word “pagan” in the description of the room’s probable use. Any ritual performed by the owner would not have been pagan to HIM.

I’m amazed by this and I’m glad that you all are able to share it