Scientists have debunked the long-standing theory that dinosaur fossils inspired the myth of the griffin.

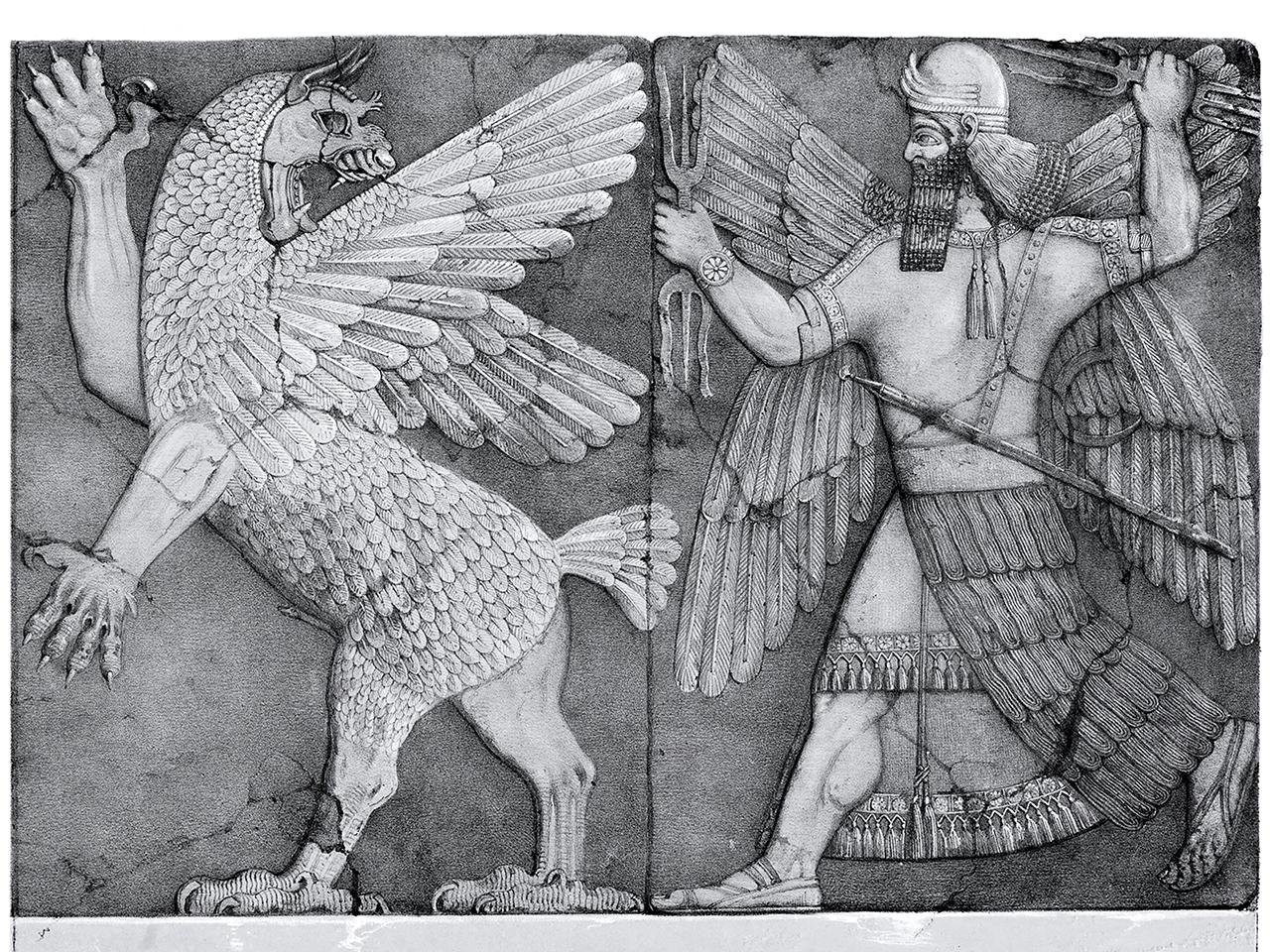

For over three decades, it was widely believed that the griffin—a legendary creature with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion—was derived from ancient fossil discoveries. However, recent research by University of Portsmouth paleontologists Dr. Mark Witton and Richard Hing suggests that the connection between Protoceratops fossils and griffin mythology is highly improbable.

The griffin has been a prominent figure in mythological art and literature since at least the 4th millennium BCE, originating in Egyptian and Middle Eastern cultures before becoming popular in ancient Greece. The theory linking griffins to dinosaur fossils was first proposed by classical folklorist Adrienne Mayor in her 1989 cryptozoology paper “Paleocryptozoology.”

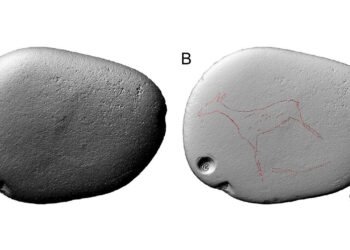

Mayor suggested that nomadic gold prospectors in Central Asia stumbled upon Protoceratops fossils and interpreted these remains as the creatures depicted in griffin lore. Protoceratops, a relative of the Triceratops, lived during the Cretaceous period about 75-71 million years ago. It stood on four legs, had beaks, and frill-like extensions on its skull, which some argued could resemble the griffin’s wings.

However, Witton and Hing’s study, published in Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, re-examined historical fossil records and consulted with historians and archaeologists. They concluded that the geographic distribution of Protoceratops fossils does not align with the locations where griffin mythology was prominent. “The suggestion that Protoceratops fossils were found by nomads prospecting for gold does not stand up because no gold has been found near known fossil sites,” Witton explained. “Even if they had been found, it is unlikely they would have been recognized as the remains of a creature.”

Witton further elaborated that ancient peoples would have only seen fragments of eroding dinosaur skeletons, making it difficult to form myths without significant effort to extract and reconstruct the bones. “There is an assumption that dinosaur skeletons are discovered half-exposed, lying around almost like the remains of recently-deceased animals,” Witton said. “But generally speaking, just a fraction of an eroding dinosaur skeleton will be visible to the naked eye, unnoticed to all except for sharp-eyed fossil hunters. It seems more probable that Protoceratops remains, by and large, went unnoticed—if the gold prospectors were even there to see them.”

The researchers also pointed out that the spread of griffin art throughout history does not support the idea that griffin lore originated from Central Asian fossils and then spread westward. “Everything about griffin origins is consistent with their traditional interpretation as imaginary beasts, just as their appearance is entirely explained by them being chimeras of big cats and raptorial birds,” Witton stated. “Invoking a role for dinosaurs in griffin lore, especially species from distant lands like Protoceratops, not only introduces unnecessary complexity and inconsistencies to their origins but also relies on interpretations and proposals that don’t withstand scrutiny.”

While the idea that fossils have inspired folklore is well-documented, with numerous examples of fossils influencing myths worldwide, Hing emphasized the importance of distinguishing between folklore with a factual basis and speculative connections. “It is important to distinguish between fossil folklore with a factual basis—that is, connections between fossils and myth evidenced by archaeological discoveries or compelling references in literature and artwork—and speculated connections based on intuition,” Hing said.

“There is nothing inherently wrong with the idea that ancient peoples found dinosaur bones and incorporated them into their mythology, but we need to root such proposals in realities of history, geography, and paleontology. Otherwise, they are just speculation.”

Adrienne Mayor, a notable figure in geomythology, drew significant attention to the links between fossils and mythology, suggesting that fossil discoveries influenced ancient tales. Her work on the griffin theory gained mainstream attention and respect. However, Witton and Hing’s re-evaluation found Mayor’s claims unconvincing.

“Some details of griffin natural history and Protoceratops fossils are similar, but these accounts do not persuasively link the two entities,” the authors noted. They also criticized the anatomical comparisons between Protoceratops and griffins, finding them inadequate.

The recent study by Witton and Hing refutes the theory that dinosaur fossils inspired the myth of the griffin. Instead, the researchers argue that griffins are best understood as purely imaginary beasts, chimeras created from the blending of big cats and raptorial birds.