In the early 1930s, the University of Cincinnati embarked on a historic excavation at Troy, led by prominent archaeologists Carl Blegen, Marion Rawson, and John L. Caskey. This monumental project unearthed nine distinct periods of reconstruction, revealing evidence of a great battle and fiery devastation, often associated with the legendary Trojan War. However, behind the celebrated names of these archaeologists were numerous local laborers, whose significant contributions remained largely unrecognized in historical records.

Jeff Kramer, an archivist and research associate in UC’s Department of Classics, has taken steps to address this oversight. Through the creation of a digital archive, Kramer aims to shed light on the invisible workers of archaeology, particularly focusing on an Albanian laborer named Emin Kani Barin, known as Kani. Kramer published his findings in the journal Bulletin of the History of Archaeology.

“These are the people who put shovels in the ground and swung the picks. They were the ones who pulled the artifacts out of the ground,” Kramer explained. “All the big excavations owe their results to these individuals who are unheralded and unacknowledged. They’re not given their due. They’re simply not mentioned.”

Kani’s story, meticulously documented by Kramer, offers a poignant illustration of the broader experiences of many workers. Originally from Albania, Kani’s life was marked by turmoil and displacement, a microcosm of the larger socio-political upheavals of the early 20th century. Following the compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923, which saw the forced relocation of over 400,000 Muslims and 2 million Greek Orthodox Christians, Kani and his family faced extreme hardship. His wife tragically succumbed to starvation in Turkey, leaving Kani to navigate a path of survival that eventually led him to the Troy excavation.

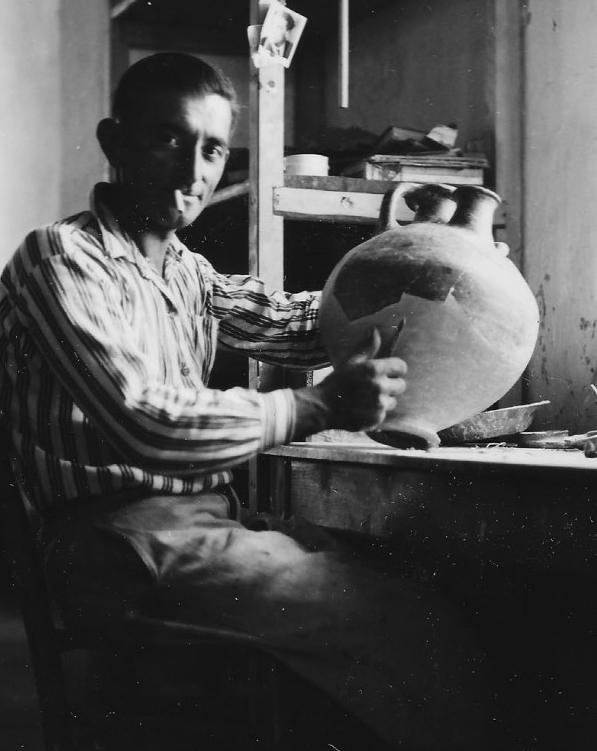

Blegen’s logs from the excavation noted Kani’s initial “particularly ragged, unshaved, and seedy-looking” appearance. Yet, employee No. 62 soon proved indispensable, translating instructions, mending pottery, and eventually being promoted to foreman. His linguistic skills and diligent work ethic made him a pivotal figure on the site. Kani’s contributions were so valued that Blegen even mentioned him in a later address to the Cincinnati Literary Club, calling him the most important worker on the dig.

While the official publications of the excavation made only brief mentions of the laborers, the personal archives tell a richer story. Kramer uncovered numerous photographs and documents that highlight Kani’s presence and impact. Images show Kani engaged in various tasks, laughing with colleagues, and even serving as a tour guide for visitors when the UC representatives were unavailable. His boundless energy and unwavering commitment are evident throughout the visual and written records.

Eric Cline, a professor at George Washington University and director of the Capitol Archaeological Institute, has studied the underappreciated contributions of local laborers in early archaeological projects. He notes that the work of these laborers was often disregarded due to class bias and a colonialist attitude prevalent at the time. “It was a very colonialist attitude but common for the day,” Cline remarked. This neglect extended to highly skilled workers, such as the Egyptian Quftis who helped unearth the tomb of Tutankhamun, yet remained uncredited in official accounts.

Cline asserts that the practice of acknowledging all contributors is more prevalent in contemporary archaeology. “Skilled workers are still invaluable at excavations today, although many budget-conscious projects more often feature student workers and volunteers. The standard today is to give credit to all of the workers who contributed to the success of a project,” he said.

Allison Mickel, an associate professor at Lehigh University and author of Why Those Who Shovel are Silent, argues that archaeological excavations reflect broader power structures in science and society, often marginalizing the local communities that support these projects. “A digger has to know what tool to use, how rough or gentle to be, when to stop, what artifacts look like and what is required to lift them from the earth undamaged,” Mickel explained. She advocates for a more inclusive approach, where local workers are seen as valued partners and beneficiaries of the scholarly outputs derived from their labor.

Kani’s correspondence with Blegen continued even after the excavation concluded in 1938, revealing a deep personal connection. Kramer emphasizes that Kani’s life, marked by war, displacement, and resilience, is emblematic of the experiences of many during that volatile period. “He was caught up in this stream that was so highly representative of what was being faced by millions of people,” Kramer said.