Scientists have successfully germinated an ancient seed discovered in a Judean Desert cave, potentially reviving a long-extinct species of tree with connections to biblical texts. Dubbed “Sheba,” the tree is believed to have grown from a seed dating back 1,000 years, found during an archaeological dig in the 1980s. The tree, now standing about 10 feet tall, belongs to the genus Commiphora, a family known for producing aromatic and medicinal resins. Researchers have speculated that Sheba may be the source of “tsori,” a healing balm mentioned in the Bible.

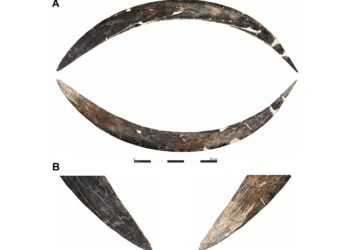

The seed, which was radiocarbon-dated to between CE 993 and 1202, was discovered in the Judean Desert, north of Jerusalem, in a region historically rich in vegetation and used for cultivation. Researchers, led by Dr. Sarah Sallon from Hadassah University Medical Center, grew the tree over a period of 14 years. The revival of this ancient seed marks a significant discovery, not only for its connection to the past but also for its potential medicinal uses today.

One of the most intriguing aspects of this discovery is its connection to “tsori,” a substance referenced multiple times in the Bible, specifically in the books of Genesis, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. Tsori, often translated as “balm” in English, was historically associated with the region of Gilead, east of the Jordan River, and was known for its medicinal properties.

Instead, researchers found that Sheba is rich in pentacyclic triterpenoids—compounds with anti-inflammatory and potential anti-cancer properties. Additionally, the leaves contain high levels of squalene, a natural substance known for its antioxidant and skin-healing benefits. These findings led the team to propose that Sheba may, in fact, be the source of the biblical tsori, which was associated with healing but not described as fragrant in ancient texts.

The tree’s discovery adds to a growing body of research focused on reviving ancient species from the Judean Desert. The excavation site, Wadi el-Makkuk, where the seed was found, has a rich history, with evidence of use by Byzantine monks and as a refuge during Jewish revolts against Rome. The seed’s origins remain somewhat mysterious, with researchers proposing that it may have been deposited in the cave either by animals or deliberately stored by humans during times of upheaval.

Dr. Sallon’s team, which includes researchers from around the world, performed extensive genetic and chemical analyses on Sheba. These analyses revealed that the tree is closely related to several southern African Commiphora species, but its exact species remains uncertain since the tree has not yet flowered. Without reproductive material, researchers cannot definitively classify Sheba or compare it to modern relatives.

Despite this limitation, the germination of Sheba provides the first evidence of its presence in the region 1,000 years ago. The findings suggest that Sheba could represent a lost lineage of trees once native to the Southern Levant, a region that includes present-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan.

The researchers are optimistic about Sheba’s future and its potential to contribute to modern medicine. Further studies on the tree’s compounds are planned, with the hope of uncovering more about its possible medicinal uses, particularly its anti-cancer properties.

While Sheba’s exact role in biblical history may remain unclear until it flowers, this remarkable discovery has already deepened our understanding of ancient plant species and their significance to human cultures.