A new study has revealed that the iconic bronze-winged lion in St. Mark’s Square, Venice, may have originated in 8th-century China.

The discovery comes from a multidisciplinary team of experts in geology, chemistry, archaeology, and art history from the University of Padua, the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, and the International Association for Mediterranean and Oriental Studies (Ismeo). Through advanced metallurgical analysis, the team discovered that a significant portion of the bronze used in the lion came from the lower Yangtze River basin in southeastern China, and it was likely cast during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE).

Lions were initially introduced to the Han court by emissaries from Persia (modern-day Iran) and had become widely represented as guardian figures.

Lead isotope analysis of the bronze alloy provided indisputable evidence of the Chinese origin of the materials used in the statue. The results were announced on September 11, 2024, during an international conference on Marco Polo, part of Venice’s celebrations marking the 700th anniversary of the famous merchant’s death. Scholars have long debated the lion’s origins, with previous theories suggesting it could have been made in Anatolia during the Hellenistic era. However, the new evidence points directly to China.

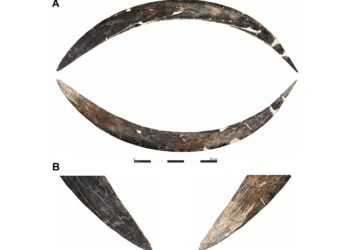

Stylistic analysis further supports this theory. Researchers found that the lion shares several design features with zhenmushou (镇墓兽), or “tomb guardian” figures, typical of the Tang Dynasty. These guardian sculptures, often placed at tomb gates to ward off evil spirits, had distinct characteristics that mirror those of the St. Mark’s lion. For instance, the lion’s wide nostrils, upturned mustache, wide-open mouth with prominent canines, and truncated orbital sockets, where horns or antlers were once mounted, are all common features of zhenmushou statues. The lion’s ears also appear to have been modified to make them look more like those of a typical lion, rather than the pointed ears seen on zhenmushou.

The lion likely traveled west along the Silk Road, a trade route that connected China with Europe for centuries. It may have passed through India, Afghanistan, and Iran before arriving in Venice, possibly in pieces, where it was reassembled and modified to fit the standard iconography of the winged lion, a symbol of Venice and Mark the Evangelist. There is no historical record of when or how the lion arrived in Venice, but it was already installed atop the column in St. Mark’s Square by the time Marco Polo returned from China in 1295.

The circumstances of its arrival remain mysterious, with some speculating that the lion could have been brought to Venice by Marco Polo’s father, Nicolò, and his uncle, Maffeo, who visited the Mongol court in Beijing between 1264 and 1266. Others believe it may have arrived earlier, perhaps during a time of intense trade along the Silk Road. The first known reference to the lion dates back to 1293, but its exact journey remains unknown.

Over the centuries, the lion has undergone several restorations. In the 1790s, Napoleon looted the statue and transported it to Paris, where it was damaged during its return to Venice in 1815. The Venetian sculptor Bartolomeo Ferrari restored the statue, making additions like the lead book beneath its paws, while retaining most of the original structure.

The lion’s Chinese origins highlight the deep cultural and economic exchanges between East and West. According to researchers from the University of Padua and Ca’ Foscari University, the lion’s journey exemplifies the far-reaching influence of the Silk Road, which connected Eastern Eurasia with Venice and the broader Mediterranean world.