Scientists have successfully extracted DNA from a 3,600-year-old cheese, making it the oldest known cheese sample ever discovered. Identified as kefir cheese, the discovery provides new insights into the origins of kefir and the development of probiotic bacteria.

“This is the oldest known cheese sample ever discovered in the world,” said Fu. “Food items like cheese are extremely difficult to preserve over thousands of years, making this a rare and valuable opportunity.” Fu emphasized that studying such artifacts can help us understand more about the diet and culture of our ancestors.

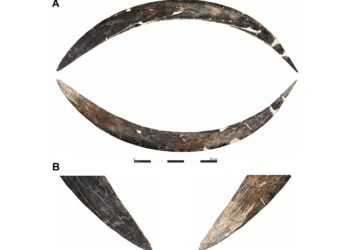

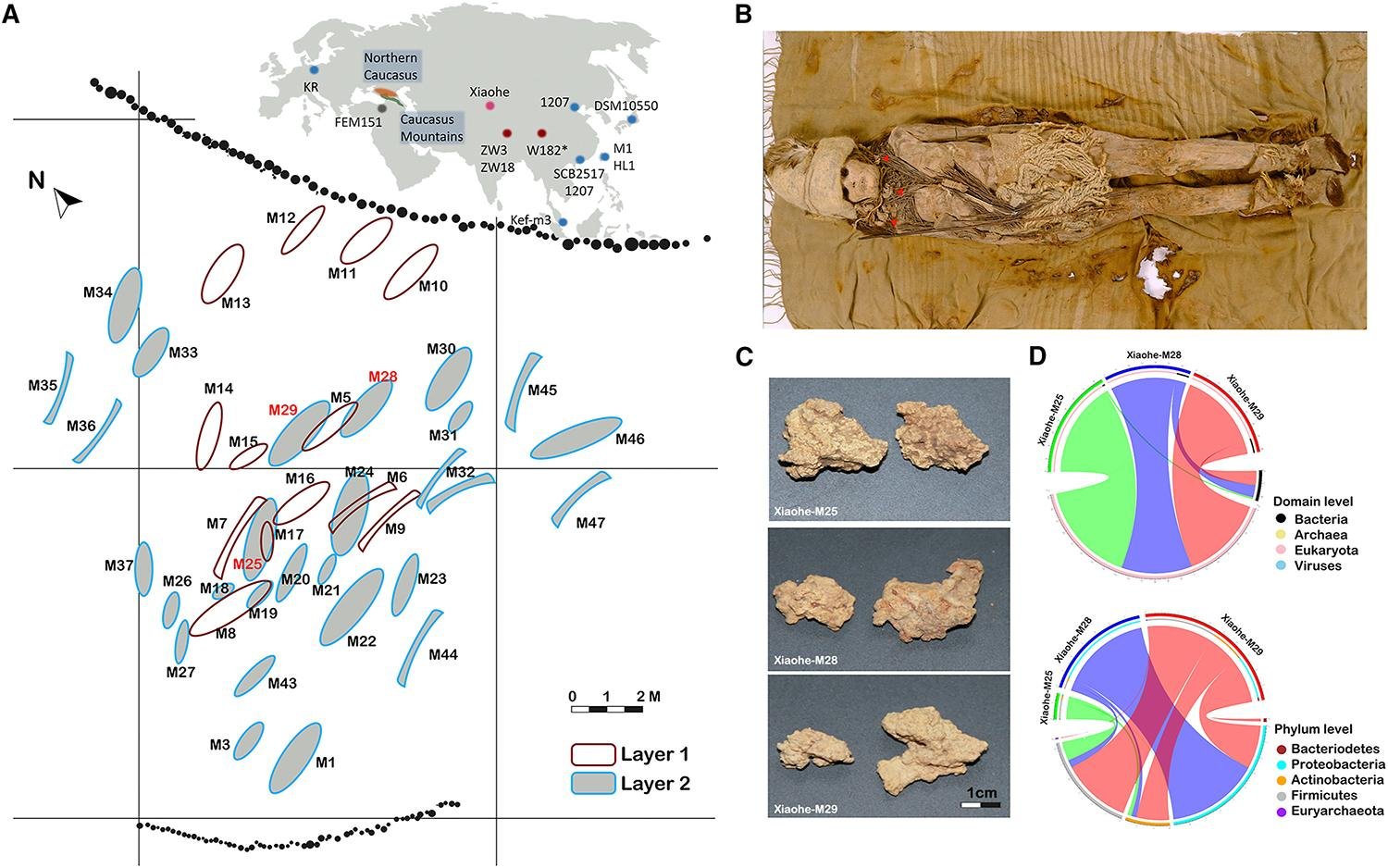

The researchers extracted mitochondrial DNA from the cheese samples, revealing that the ancient Xiaohe people used separate batches of cow and goat milk, unlike the mixed milk cheese-making traditions found in regions like Greece and the Middle East. Further genetic analysis showed that the cheese contained species of bacteria and yeast, including Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens and Pichia kudriavzevii, both of which are commonly found in present-day kefir grains. These grains are symbiotic cultures of bacteria and yeast that ferment milk into kefir cheese, much like the process used in sourdough bread.

One of the most significant findings of the study was the discovery that the Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens in the ancient cheese was closely related to a strain found in Tibet. This challenges the long-held belief that kefir originated solely in the Caucasus Mountains of Russia. According to Fu, the study suggests that kefir culture may have been maintained in northwestern China since the Bronze Age.

The ancient kefir cheese also contained higher levels of Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens than are typically found in modern varieties, which would have made the cheese more likely to trigger immune responses in the human digestive system. Over the last 3,600 years, the bacteria seem to have evolved alongside humans, becoming less likely to cause such immune reactions. “This is an unprecedented study, allowing us to observe how a bacterium evolved over the past 3,000 years,” Fu said. The genetic exchanges between strains have enhanced the stability of the bacteria, improving their milk fermentation capabilities over time.

The presence of kefir cheese in the Xiaohe tombs raises intriguing questions about its significance in ancient burial practices. While the exact reason for smearing cheese on the mummies remains unclear, one theory is that the cheese may have served as a delicacy for the deceased in the afterlife. The Xiaohe people might have believed that this rare food could sustain the spirits of the dead or play a ritualistic role in the burial process.

The findings were published on September 25 in the journal Cell.