In a groundbreaking study published in Scientific Reports, Griffith University researchers employed advanced biomechanics technology to assess the striking capabilities of two iconic Indigenous Australian weapons: the kodj and the leangle, the latter traditionally paired with a parrying shield.

This research, conducted by experts at the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution and the Griffith Centre of Biomedical and Rehabilitation Engineering, marks the first time that human and weapon efficiencies have been scientifically evaluated for these Aboriginal weapons. According to Associate Professor Michelle Langley, this study opens the door to understanding the impact of hand-held weaponry on the human body throughout history.

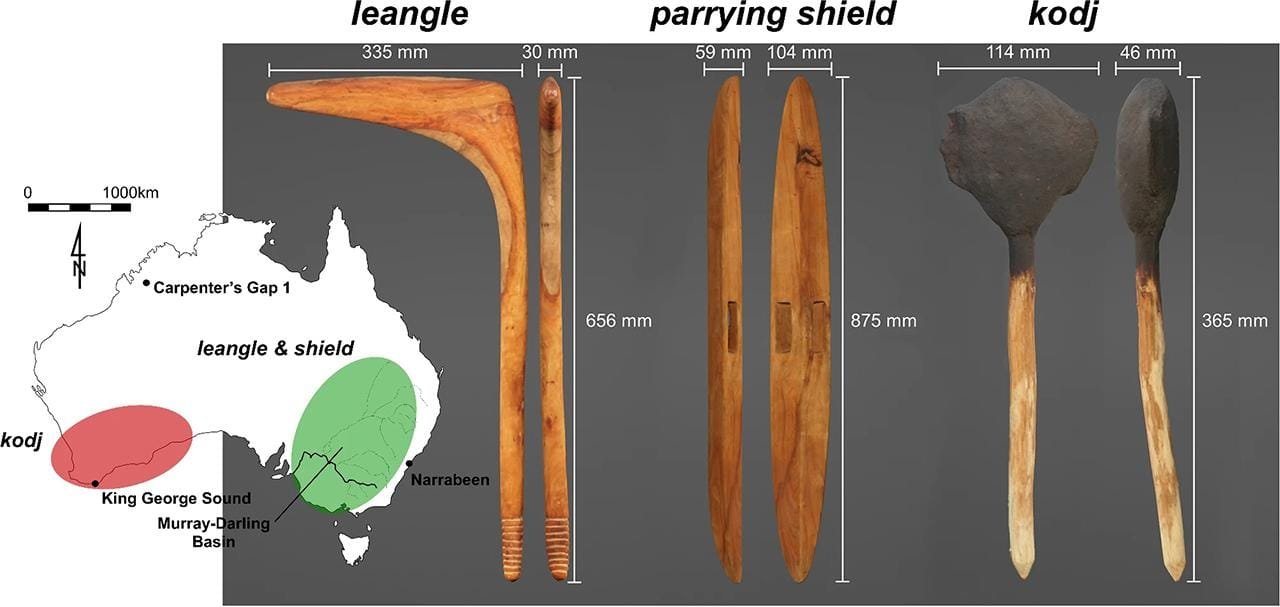

The kodj, a versatile tool with origins potentially spanning tens of thousands of years, combines elements of a hammer, axe, and poker. Crafted with a handle made from wattle wood and a sharpened stone blade secured with balga resin, it was made by Larry Blight, a Menang Noongar expert from Western Australia. The leangle, on the other hand, is a fighting club with a hooked striking head typically crafted from hardwood, traditionally used in conjunction with a parrying shield. This set of weapons, created by Brendan Kennedy and Trevor Kirby on Wadi Wadi Country, served as the focus of biomechanical analysis in the study.

Despite extensive archaeological investigations into ancient weaponry, no previous study had quantified human biomechanics or weapon efficiency when striking with handheld tools. The research team, led by Associate Professors Michelle Langley and Laura Diamond, undertook this challenge at the invitation of First Weapons, an ABC TV documentary series produced by Blackfella Films. In this series, host Phil Breslin demonstrated the physical demands of using these weapons, which were analyzed by the researchers through wearable instruments that tracked kinetic energy, velocity, and joint movements at the shoulder, elbow, and wrist.

The study found that the leangle proved to be the deadlier of the two weapons in terms of delivering powerful blows to the human body. While the kodj allowed for easier maneuverability and precision due to its adaptable design, it too was capable of inflicting lethal damage. “The leangle is far more effective at delivering devastating blows to the human body,” said Associate Professor Laura Diamond. She further noted, “Our biomechanical evaluation of the kodj and leangle strikes provides the first understanding of the coordinated movement and energy expenditure required to use these weapons effectively.”

Historically, Aboriginal communities developed various weapons not only for warfare but also as tools for dispute resolution. In such contexts, people sometimes faced projectiles, unarmed or with shields, as part of a “trial by ordeal.” These ordeals, while often resulting in injuries, were intended to avoid death. The leangle and shield, frequently used in close combat, likely played roles in such conflict scenarios, as evidenced by the occurrence of defensive wounds on skeletal remains—often called “parrying fractures”—discovered by archaeologists.

The research sheds light on how human anatomy itself may have adapted in relation to weapon usage, possibly linked to the evolution of the hand’s structure in Homo sapiens. Studies of modern chimpanzees suggest that while they may use objects in displays of aggression, they rarely direct them towards other individuals with precision. In contrast, humans have designed and wielded hand-held weapons for millennia, a trait unique to our species. “The methods applied in this study could be adapted to investigate other ancient weapons globally, facilitating comparative research across different cultures and time periods,” Diamond added.

This study points to the importance of understanding biomechanics in the study of human history. As Langley noted, while the design of a weapon is essential, its efficacy ultimately depends on the human delivering the strike.

The study has been published in Scientific Reports.