Archaeologists have unearthed an ancient rock-shelter in the Zeravshan Valley of Tajikistan, providing evidence of human presence spanning over 130,000 years.

The site, known as Soii Havzak, is believed to have been a migration route for several early human species, including Neanderthals, Denisovans, and early Homo sapiens. Led by Professor Yossi Zaidner from the Institute of Archaeology at Hebrew University and Dr. Sharof Kurbanov from the National Academy of Sciences of Tajikistan, the research has been published in the journal Antiquity.

“This discovery marks a significant step toward understanding ancient human history in Central Asia,” Zaidner said in a statement. “The Zeravshan Valley, known primarily as a Silk Road route in the Middle Ages, was a key migration route for early humans long before that, dating back between 20,000 and 150,000 years.” The valley’s location within the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor (IAMC) likely facilitated human movement across regions and supported encounters between different human species. Researchers have long recognized the IAMC’s importance in Stone Age migrations, yet the region remains underexplored, according to Zaidner. The team’s findings from Soii Havzak could offer essential clues on how human groups, such as modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans, interacted in the area.

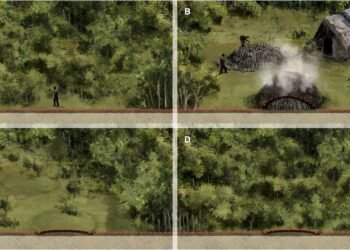

Soii Havzak is situated along a small tributary of the Zeravshan River, approximately 10 kilometers north of Panjakent and close to the Uzbekistan border. The site itself is a natural rock-shelter carved into a cliff face, about 40 meters above the stream. During excavations, the team uncovered over 500 artifacts, including stone tools, blades, and flakes, many of which date back to the Middle and Upper Paleolithic periods. Additionally, bones and organic materials, such as burnt wood and charcoal, were found in the shelter, suggesting fire use and possible settlement.

The artifacts point to several phases of human occupation, with evidence of early human activity dating back as far as 150,000 years. “The preservation of organic materials, such as burnt wood remains and bones, is remarkable,” said Zaidner, adding that these findings could provide valuable information on the ancient climate of the Zeravshan Valley. This preservation offers researchers the potential to reconstruct past environments and climates, which may illuminate how early human populations adapted and evolved within this mountainous region.

Dr. Sharof Kurbanov emphasized the importance of this site as a transition point that enabled ancient human populations to spread across Central Asia and beyond. “The rich findings from Soii Havzak add to our understanding of the development of human populations and behaviors in Central Asia,” Kurbanov noted.

Although the initial findings are substantial, researchers hope to gain more insights from the ongoing excavations and plan to conduct radiometric dating to establish a precise timeline for the various occupation phases. According to Zaidner, further research at the site is crucial to determining which specific human populations inhabited the Zeravshan Valley and the nature of their interactions. He expressed optimism that deeper layers of excavation might reveal skeletal remains that could help identify the hominin groups represented at Soii Havzak.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

Truly enjoy reads about the scientific discoveries of pre history.