A new study revealed key insights about Mediterranean language families’ origins, including Italo-Celtic and Graeco-Armenian branches of Indo-European. An international team of geneticists and archaeologists conducted this research. They examined how ancient migrations influenced the emergence of linguistic groups that shaped Mediterranean civilizations.

The team published their findings on the preprint server bioRxiv. They analyzed genetic data from 314 ancient individuals who lived in the Mediterranean 5,200 to 2,100 years ago. The researchers used advanced genome sequencing and strontium isotope analysis. This revealed significant genetic and cultural differences between eastern and western Mediterranean populations.

The study pinpoints two key migration patterns that had an impact on the genetic and linguistic roots of the Mediterranean. People in the Western Mediterranean, including those in Spain, France, and Italy today felt the influence of the Bell Beaker culture, a group with origins in Western Europe. This culture is linked to the rise of Italic and Celtic languages.

In contrast, populations in the eastern Mediterranean, like those in Greece and Armenia, showed direct genetic input from the Yamnaya, a group of herders from the Western Steppe area covering parts of today’s Ukraine southern Russia, and Kazakhstan. These movements set the stage for the development of classical Greek and Armenian languages. The findings align with the linguistic hypotheses of Italo-Celtic and Graeco-Armenian.

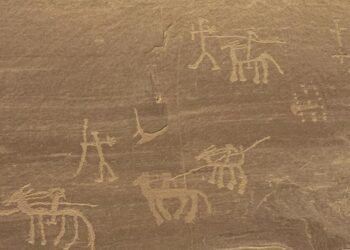

The genetic evidence supports linguistic theories about how Indo-European languages diverged in the Mediterranean. The researchers showed how people from the steppes brought their genes and introduced big cultural changes. These included chariot technology and advanced metallurgical techniques, which local societies adopted.

In Italy, people of the Bronze Age in the north and central parts had genes linked to the Bell Beaker culture. This ancestry matches the Italic languages, including Latin, which later spread across the peninsula. On the other hand, people in southern Italy and along the Adriatic coast showed more Yamnaya influence mirroring the genetic patterns seen in Greek and Balkan groups.

The results question older ideas, like the Italo-Germanic theory, which proposed closer language connections between Italic and Germanic languages. The research also uncovered complex situations such as mixed genetic heritage in the Balkans coming from Bell Beaker Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures.

The study highlights the Mediterranean as a lively center of genetic and cultural mixing during the Bronze Age. Cyprus, for example, became a crossroads for influences from Greece, the Levant, and Anatolia. In the same way, ancient Italian groups showed varied ancestry combining local Neolithic farmer lines with newcomers from Central Europe.

The study is a big step forward in grasping how Indo-European languages split up in their early days. While the findings clear up many points about how languages branched off, they still don’t answer everything. For example, we’re still not sure about the exact links between all parts of the Indo-European family tree.

By combining genetics, archaeology, and linguistics, this research offers a strong way to explore how human history is all tied together.