One of the world’s oldest scrolls, dating back two millennia, originating from the lost Roman city of Herculaneum, long considered unreadable because of the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, has yielded the first decipherable words thanks to new technology. By employing artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced X-ray imaging techniques, scientists have been able to virtually unroll the fragile papyrus and reveal lost words in ancient Greek.

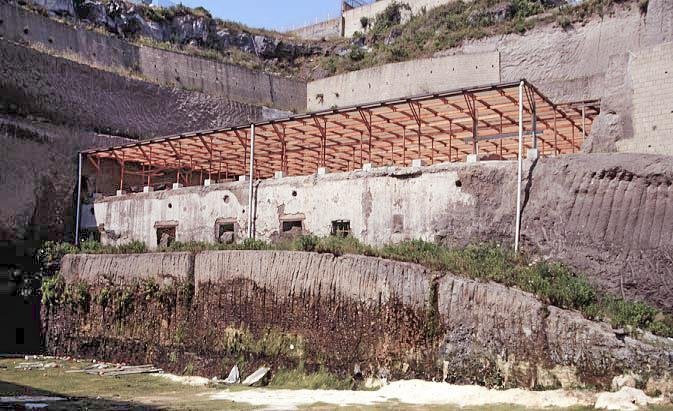

The charred scroll, known as PHerc. 172, is among many unearthed at the Herculaneum ruins, a city that, like Pompeii, was destroyed in the eruption. The intense heat carbonized the scrolls, making them too brittle to physically open. For centuries, academics have worried that these texts—believed to contain philosophical works of antiquity—would forever be unreadable. Nevertheless, through a collaborative effort between academics, computer scientists, and engineers, great strides have been achieved.

Using a synchrotron—a particle accelerator that produces powerful X-rays—scientists at the UK’s Diamond Light Source scanned the scroll to create a 3D reconstruction. AI algorithms developed as part of the Vesuvius Challenge competition then analyzed the scans to detect ink hidden within the papyrus layers.

“This scroll contains more recoverable text than we have ever seen in a scanned Herculaneum scroll,” said Dr. Brent Seales, a co-founder of the Vesuvius Challenge and principal investigator of the EduceLab at the University of Kentucky. “Despite these exciting results, much work remains to improve our software methods so that we can read the entirety of this and the other Herculaneum scrolls.”

Among the first words deciphered from PHerc. 172 are ἀδιάληπτος (‘foolish’), διατροπή (‘disgust’), φοβ (‘fear’), and βίου (‘life’). All of these words suggest that the scroll could be a work of the philosopher and poet Philodemus of Gadara, one of the leading Epicureans of the 1st century BCE. According to scholars, this hypothesis is corroborated by the writing style, which coincides with other texts attributed to Philodemus, and by the thematic use of the word “foolish”, characteristic of his writings.

The findings have sparked excitement in the academic world. “It’s an incredible moment in history as librarians, computer scientists, and scholars of the classical period are collaborating to see the unseen,” said Richard Ovenden, head of Gardens, Libraries, and Museums at the University of Oxford. “The astonishing strides forward made with imaging and AI are enabling us to look inside scrolls that have not been read for almost 2,000 years.”

The story behind PHerc. 172 is as interesting as its text. Excavated from the ruins of a grand Roman villa, believed to have belonged to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, in the 1750s, the scroll was gifted in the early 19th century by King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Sicily to the soon-to-be King George IV of the United Kingdom. Reportedly, the exchange included a peculiar trade: King George received several scrolls in return for a shipment of kangaroos.

Housed today at the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford, PHerc. 172 is one of three Herculaneum scrolls currently in the collection. In contrast to the other “Herculaneum papyri”, the writing ink on this scroll is much denser and therefore more visible to X-ray scans. Researchers believe this characteristic will help refine the AI’s ability to decipher more of the text.

The Vesuvius Challenge, launched in 2023 by Brent Seales and Silicon Valley sponsors, has played a crucial role in advancing the ability to read these scrolls. The challenge encouraged researchers worldwide to develop AI tools for analyzing the 3D scans, resulting in major breakthroughs. Last year, a team of students, including Youssef Nader (Germany), Luke Farritor (U.S.), and Julian Schilliger (Switzerland), won the $700,000 grand prize after successfully identifying more than 2,000 Greek letters from another scroll.

While the latest discoveries from PHerc. 172 mark a step forward, there is still much more to be done. AI technology can recognize ink but does not fully recognize letters or interpret language. Human experts have to manually piece together the text and interpret its meaning.