A painted chamber tomb from the mid-5th century BCE was discovered in the Monterozzi Necropolis of Tarquinia, Italy. The tomb, which was first detected in late 2022 but only recently announced, reveals vibrant wall frescoes depicting scenes of dance and a workshop of artisans. This is the first painted burial with a figurative frieze to be unearthed in Tarquinia in a century.

The tomb was discovered during an inspection by archaeologists from the Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape of Southern Etruria. Researchers identified the partially buried chamber—now designated as Tomb 6438—while examining looted and collapsed tombs.

Archaeo-speleologists working in the area came across a collapse along the left wall, exposing an intact burial chamber behind the debris, much to their surprise. Due to concerns over potential looting, the Superintendence kept the discovery confidential until the structure could be secured and stabilized.

According to Daniele Maras, the archaeologist responsible for the discovery and now director of the National Archaeological Museum of Florence, the excavation revealed an intricate history of both natural and human disturbances. “After restoring access to the burial chamber and installing a metal door, the archaeological excavation demonstrated that all the material collected did not belong to the grave goods of the painted tomb, which dates back to the mid-fifth century BCE, but had fallen from the upper tomb, more than a century older, from the end of the Orientalizing period,” Maras said.

The painted tomb was dug deep beneath an existing burial site. Grave robbers breached the tomb’s sealing slab in antiquity and emptied it of its original funerary objects. Later, the collapse of the overlying tomb caused debris and artifacts, including fragments of Attic red-figure pottery, to fall into the chamber. Despite all this, however, the most important aspect of the tomb, the frescoes, remained remarkably preserved.

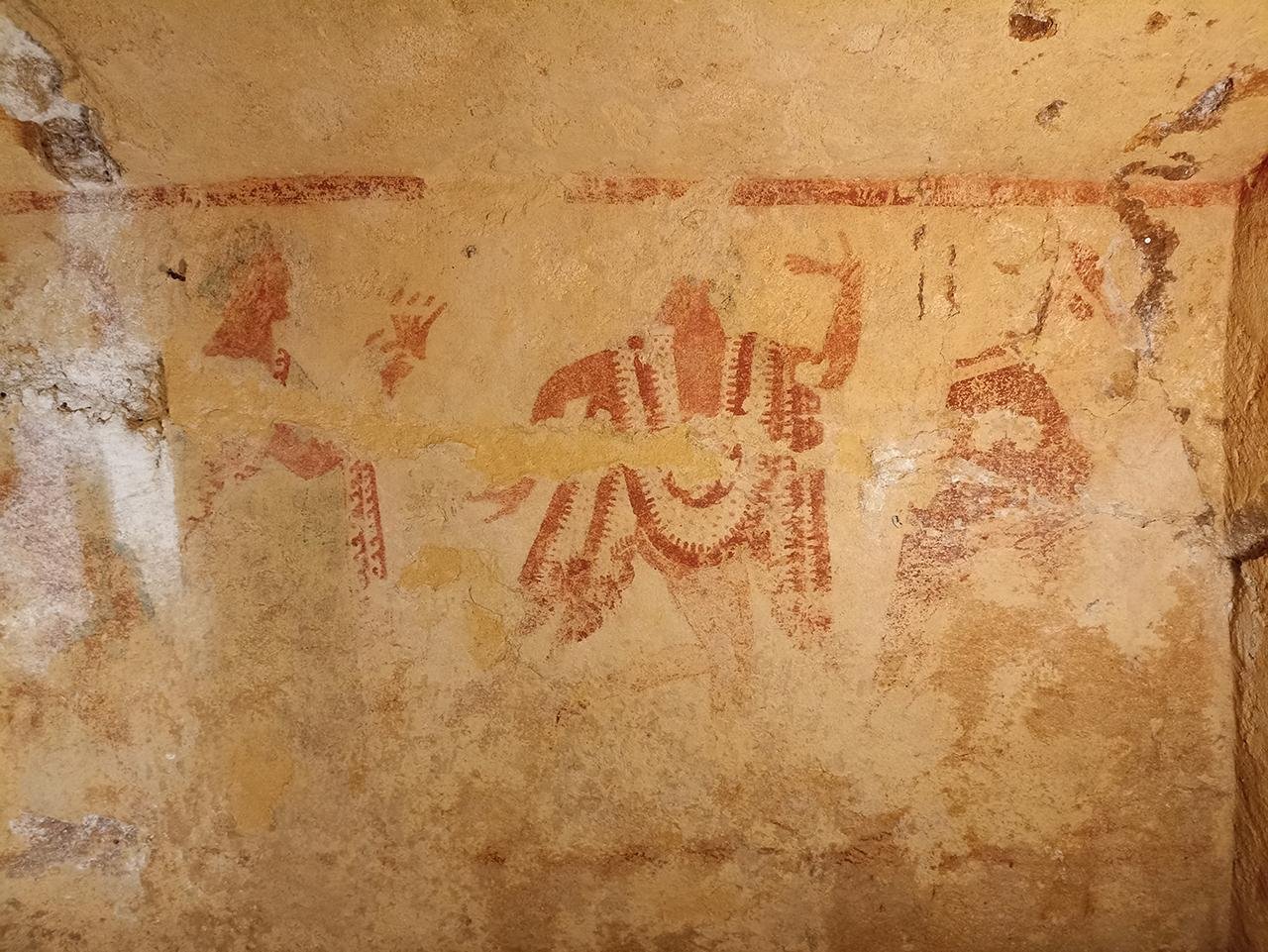

The painted walls of the tomb provide a view into Etruscan culture and beliefs that are almost unequaled. The left wall is the best preserved; it bears a lively scene of four figures—two men and two women—dancing to the sound of a flutist. This depiction reflects the Etruscans’ deep appreciation for music and festivity.

The back wall is more damaged from the collapse of the structure but shows one woman, possibly the deceased, accompanied by some young men. The right wall, currently obscured by mineral deposits, is fascinating because it reveals a metallurgical workshop in use. It has been suggested that this may represent the mythical forge of Sethlans, the Etruscan equivalent of Hephaestus, or a depiction of the deceased’s family trade.

Superintendent Margherita Eichberg said: “The extraordinary quality of the paintings is already evident in the first restoration, carried out by Adele Cecchini and Mariangela Santella, which highlights the refined details of the flute player and one of the dancers.”

Due to the tomb’s delicate condition, an extensive conservation project is underway. The restoration specialists are reinforcing the walls of the tomb, enhancing the visibility of the frescoes, and conducting multispectral imaging analysis on the pigments to reconstruct their original colors. To further protect the tomb, a small guardhouse will be built at the entrance to maintain a stable climate inside the chamber.