Recent archaeological research has revealed that the Flagstones monument near Dorchester, Dorset, is the earliest known circular enclosure in Britain. The results of advanced radiocarbon dating have placed it around two centuries older than previously estimated. Published in Antiquity by researchers from the University of Exeter and Historic England, these findings shed new light on the evolution of monumental architecture in Neolithic Britain.

Discovered in the 1980s when the Dorchester bypass was being built, Flagstones is a nearly perfect circular enclosure, with an approximately 100-meter diameter ditch originally composed of intersecting pits and likely accompanied by an earthwork bank. The monument is now partly under the bypass, with the other half beneath Max Gate, which was once home to Thomas Hardy and is now managed by the National Trust.

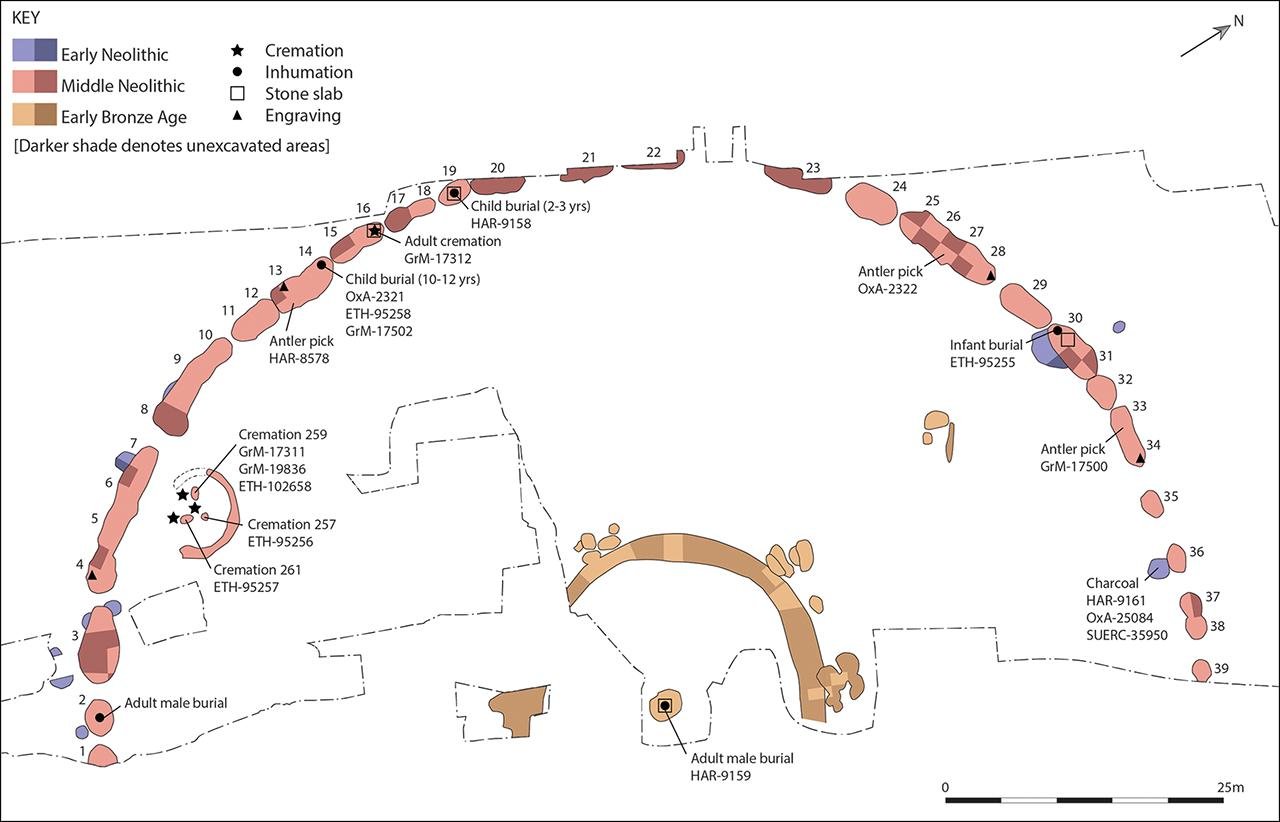

Within the site, archaeologists discovered several significant artifacts, including human remains, red deer antlers, and charcoal, which underwent radiocarbon analysis at ETH Zürich and the University of Groningen. The findings suggest that early Neolithic use of the site, including pit digging, began around 3650 BCE. However, the circular enclosure was constructed around 3200 BCE, with burials placed in its pits shortly after.

Dr. Susan Greaney, a specialist in Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments at the University of Exeter, said: “Flagstones is an unusual monument; a perfectly circular ditched enclosure, with burials and cremations associated with it.” She added that we weren’t sure where it fit in the broader sequence of Neolithic monuments, but the new dating places it in a much earlier period than we had expected.”

The new research has a fascinating connection to Stonehenge. The first phase of Stonehenge, from about 2900 BCE, features a circular ditch and burial practices similar to Flagstones. This has led some experts to suggest Stonehenge may have been inspired by Flagstones.

“The chronology of Flagstones is essential for understanding the changing sequence of ceremonial and funeral monuments in Britain,” said Dr Greaney. “Could Stonehenge have been a copy of Flagstones? Or do these findings suggest our current dating of Stonehenge might need revision?”

Flagstones also shares similarities with other Stone Age sites, not just Stonehenge. It resembles Llandygái ‘Henge’ A in Gwynedd, Wales, and several locations in Ireland. Artifacts and burial customs found at these sites show that Neolithic communities across Britain and Ireland shared some cultural traits. This supports the idea that these prehistoric societies were not isolated but engaged in widespread exchanges of traditions.

The exact function of Flagstones in Neolithic society is still debated. However, the burials found there suggest a more ceremonial role for the site, with at least four individuals buried within its enclosure pits: a cremated adult and three uncremated children, as well as three other partial cremations elsewhere. Around a thousand years later, a young adult male was buried under a large sarsen stone at the site’s center,

indicating that it remained in use for an extended period.

Similar patterns have been observed at Stonehenge, where archaeologists unearthed at least 64 cremations accompanied by evidence suggesting that maybe 150 individuals were buried there. This supports the theory that these kinds of monuments were multi-purpose ceremonial sites and not just burial grounds.

The discovery that Flagstones predates Stonehenge challenges historic narratives regarding the development of Neolithic monumental architecture in Britain. While Stonehenge has long been considered the pinnacle of Neolithic construction, Flagstones may reflect an earlier stage in the tradition of circular enclosures. The study highlights how interconnected Neolithic societies were, sharing architectural practices and ritual traditions across vast distances.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

I am starting to conceptualize these circular stone monuments were in effect an ancient telephone system using very low frequencies as the carrier wave where half the wave would travel through the Earth and the other half through the air,The stones were set up in such a manner that peoples voices would be picked up and sent or received.