In the dry plains of ancient Nubia—modern-day Sudan—women were not just pillars of their households but true bearers of the community’s weight, according to a groundbreaking interdisciplinary study published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

The study, led by Jared Carballo of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Uroš Matić of the University of Essen, sheds much-needed light on the labor contributions of Nubian women 3,500 years ago during the Bronze Age.

The study centers on 30 individuals—14 women and 16 men—who were interred at Abu Fatima, a cemetery linked to the Kerma culture, a powerful Nubian kingdom contemporaneous with ancient Egypt. Analyzing skeletal remains alongside ethnographic and iconographic data, the researchers identified stark contrasts in the physical wear and tear on women and men, graphically detailing gendered labor roles firmly embedded in daily life.

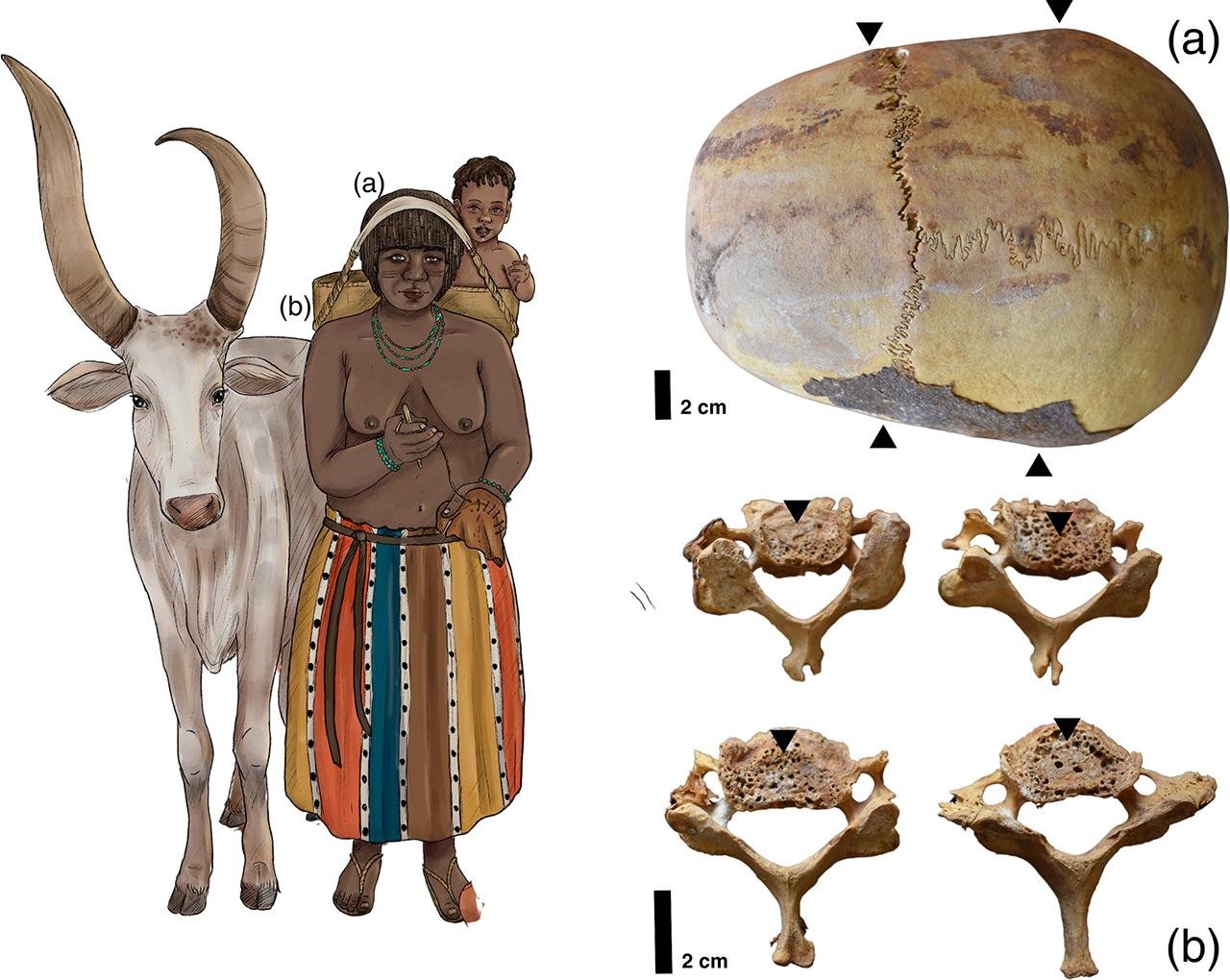

Male skeletons had signs of shoulder strain and arthritis, particularly on the right, from repeated one-shoulder load carrying. Female skeletons showed extreme changes in their cervical vertebrae and skulls, typical of decades-long use of head straps—known as tumplines—used to carry heavy loads. These changes show years, even decades, of weight transfer from the forehead to the spine.

The most important discovery was “individual 8A2,” a woman over 50 years old, who was buried with high-status items such as an ostrich feather fan and a fine leather pillow. Despite these elite burial markers, the most pronounced evidence of tumpline use was presented by her bones, which had the deepest cranial depression and advanced cervical osteoarthritis. Biochemical analysis of her tooth enamel confirmed that she was a migrant, perhaps highlighting how she lived both as a carrier of physical burdens and cultural heritage.

“This way of life is as common as it is overlooked by written history,” explains Carballo. “In some way, the study reveals how women literally have carried the weight of society on their heads for millennia.”

In fact, this research contradicts the male-centric narrative typically dominating prehistoric depictions of labor. While written history neglects the toil of women, Abu Fatima’s bones speak for themselves. The wear patterns on their bones offer a form of biography—evidence of repeated, hard labor influenced not just by survival but by social needs and inherited techniques.

Scholars note that this physical work was not exclusive to the lower classes. The case of individual 8A2 complicates assumptions that upper-class women were free from manual work. The researchers say that the persistence of head-loading techniques all over the globe—from Africa to the Himalayas and Latin America—testifies to a universal but lesser-understood type of endurance and skill.

Through a combination of skeletal analysis, ancient tomb imagery, and comparisons with contemporary ethnographic records, the study reveals new avenues for interpreting gendered labor, the physical implications of motherhood, and the intangible strength contained within women’s roles across the centuries.