A sweeping new research study has shifted our image of the Maya civilization of the ancient past, and it appears that its population during the Late Classic period (CE 600–900) might have reached as high as 16 million people, roughly 45% higher than previous estimates. The research, led by Tulane University’s Middle American Research Institute (MARI) and published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, employs one of the largest regional-scale lidar (light detection and ranging) analyses ever conducted in the Central Maya Lowlands.

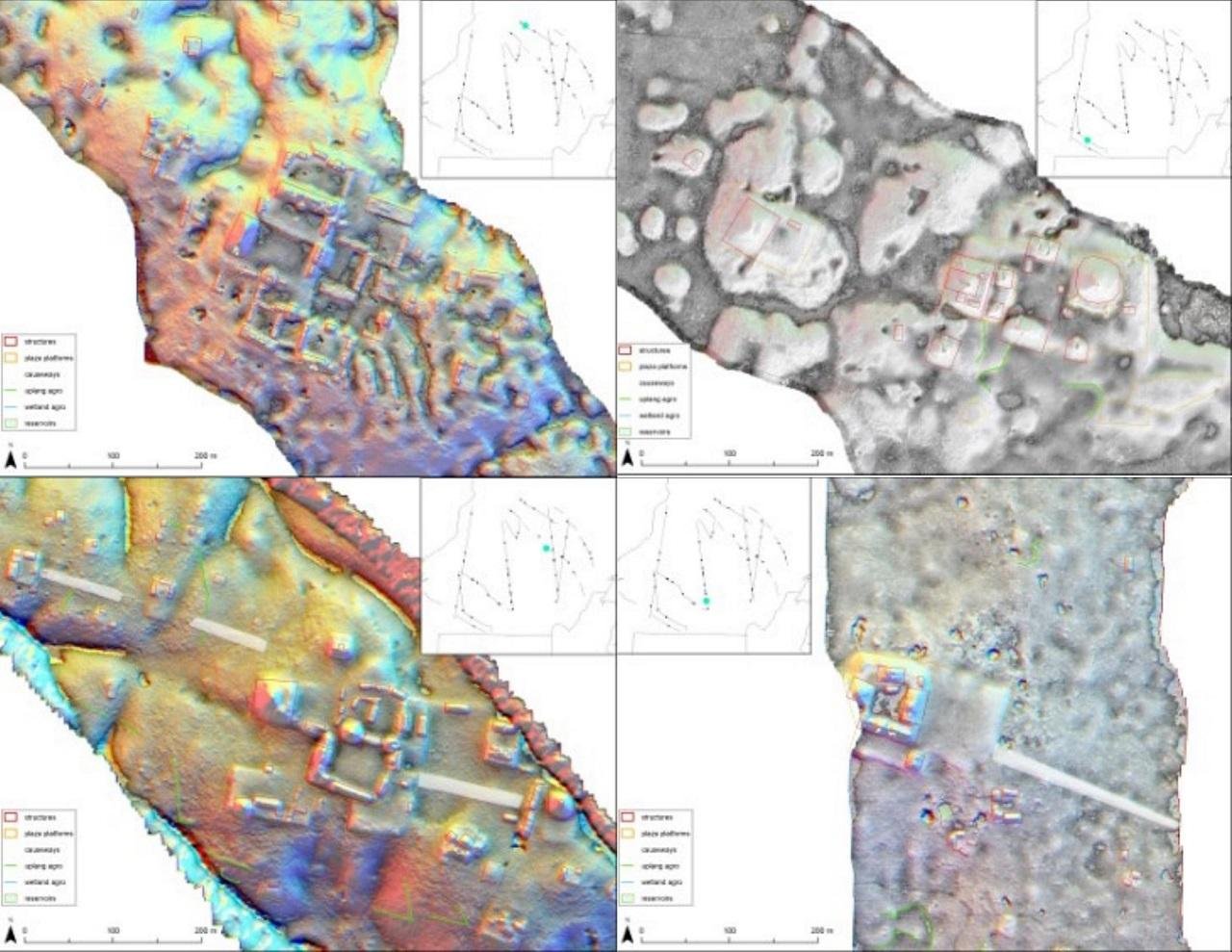

The team, directed by Francisco Estrada-Belli, reprocessed and merged both publicly and privately commissioned lidar data sets — such as environmental lidar collected by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center — to map 95,000 square kilometers of regions in modern Guatemala, southern Mexico, and western Belize. The high-resolution images not only demonstrated a population greater than that previously estimated, between 9.5 million and 16 million, but also revealed a very uniform model of settlement and agriculture in both rural and urban zones.

“We expected a modest increase in population estimates from our 2018 lidar analysis, but seeing a 45% jump was truly surprising,” Estrada-Belli said. “This new data confirms just how densely populated and socially organized the Maya Lowlands were at their peak.”

Contrary to the common supposition that rural settlements were isolated, nearly all settlements discovered during the survey were within a five-kilometer radius of a large or medium plaza group, which are civic-ceremonial centers controlled by elites. The findings show that rural communities were fully embedded in networks of religious, economic, and political interaction. “No rural community could be regarded as isolated, disembedded, or independent,” the researchers stated.

Lidar imagery also revealed extensive agricultural infrastructure, particularly in the densely populated north, which pointed toward elite control of food production and distribution. Across the region, settlements followed a consistent pattern: residential and farm zones clustered around groups of elite plazas, which formed tiered administrative and exchange networks. The plazas may have been marketplaces, further reinforcing the interconnectedness of Maya society.

The research paints a picture of a civilization that was not a collection of independent city-states but an interwoven complex of governance, trade, and agriculture across large areas of tropical forest. While a highly organized society could have enhanced resilience to localized shortages, the huge population scale and interdependence may have made the Maya vulnerable to ecological stress and political instability in the centuries leading to their downfall.

The descendants of the Maya, some eight million in total, continue to live today in southern Mexico and Central America, preserving aspects of a cultural legacy every bit as remarkable as it is complex.

More information: Tulane University

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.