Archaeologists have made a breathtaking find at Saqqara that is transforming the study of artistic traditions in ancient Egypt. A 2021 discovery at Gisr el-Mudir, a limestone statue, shows a nobleman and his family presented in a form that combines traditional three-dimensional carving with groundbreaking relief work, an approach previously unknown in Old Kingdom sculpture.

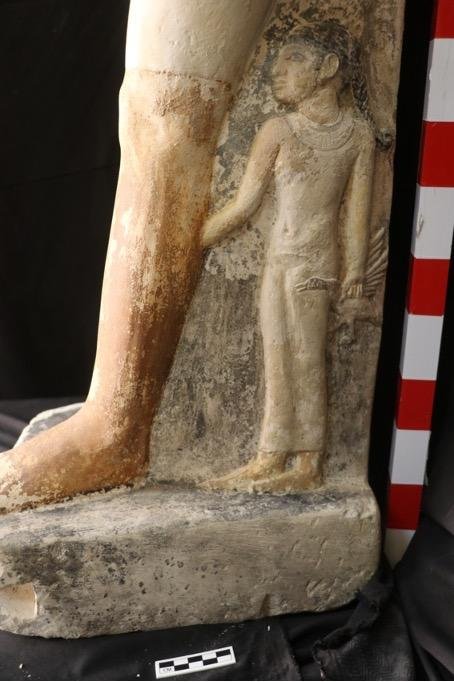

The study, published in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology by Dr. Zahi Hawass and Dr. Sarah Abdoh, describes the statue as a departure from expected norms. The figure at the center is a nobleman standing in a left-foot-forward stance, a common Old Kingdom pose representing vitality and strength. He wears a short, lappet wig and a finely pleated kilt, and his well-modeled torso reveals the sculptor’s attention to anatomical detail. Beside him, his wife kneels at his right leg, her small scale reinforcing her supporting role. She wears a simple sheath dress with a broad collar and a shoulder-length wig.

What distinguishes this statue from all others of its kind is the inclusion of a daughter carved not in the round but in bas-relief. Standing behind the left leg of her father, the girl grasps it with one hand and holds a goose in the other—a gesture perhaps representing provisions for the afterlife. What is especially striking about this is the combination of sculptural methods in one work, for which there is no precedent in the known artistic tradition of the Old Kingdom.

The statue was unearthed without archaeological context, likely discarded by early tomb looters. Its precise date was ascertained through stylistic analysis. It was compared with other family statues, specifically the limestone statue of Irukaptah at the Brooklyn Museum, also from Saqqara. Both are very close in terms of height, proportion, clothing, and artistic execution. These affinities strongly suggest that the Gisr el-Mudir statue dates to the Egyptian Fifth Dynasty and was created by the same artistic “school” as the Irukaptah statue.

The discovery has broader implications for Egyptology. For generations, experts referred to the strict conventions of Old Kingdom art, where figures were portrayed with little room for experimentation. The Gisr el-Mudir statue demonstrates that sculptors managed to blend tradition and innovation, introducing creative solutions even within established forms of family representation.

Dr. Zahi Hawass shared further insights with Archaeology News Online Magazine via email: “I found the statue hidden under the sand, and nearby was a false door inscribed with the name ‘Messi.’ The symbolic meaning of this artifact may indicate a connection with family, suggesting that they will reunite in the afterlife, as they did in life.” In addition, the tomb lacks inscriptions, and the scene depicting the daughter with a goose reflects daily life, serving a similar function to scenes usually found on tomb walls.

Dr. Hawass also noted the importance of the relief carving: while high relief is usually associated with later periods, such as the Ptolemaic era, the statue proves the skill was already familiar even 4,300 years ago. The integration of relief and three-dimensional carving, he further observed, makes the statue the only known example of its kind from the Old Kingdom—a unique masterpiece of innovation reshaping our understanding of Old Kingdom Egyptian art.

The find underscores Saqqara’s role as a major burial ground and a center of artistic innovation during Egypt’s Old Kingdom. Through the blending of conventional forms and new techniques, the family statue from Gisr el-Mudir demonstrates that Egyptian sculptors were more flexible and imaginative than traditionally understood.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.