Archaeologists have unearthed monumental rock art and artifacts in northern Saudi Arabia that contradict conventional assumptions about when human beings originally inhabited the deserts of the region. The carvings, dated between 12,800 and 11,400 years ago, are the oldest direct archaeological proof of human settlement in the Arabian interior during a period long thought to be too dry to allow human life.

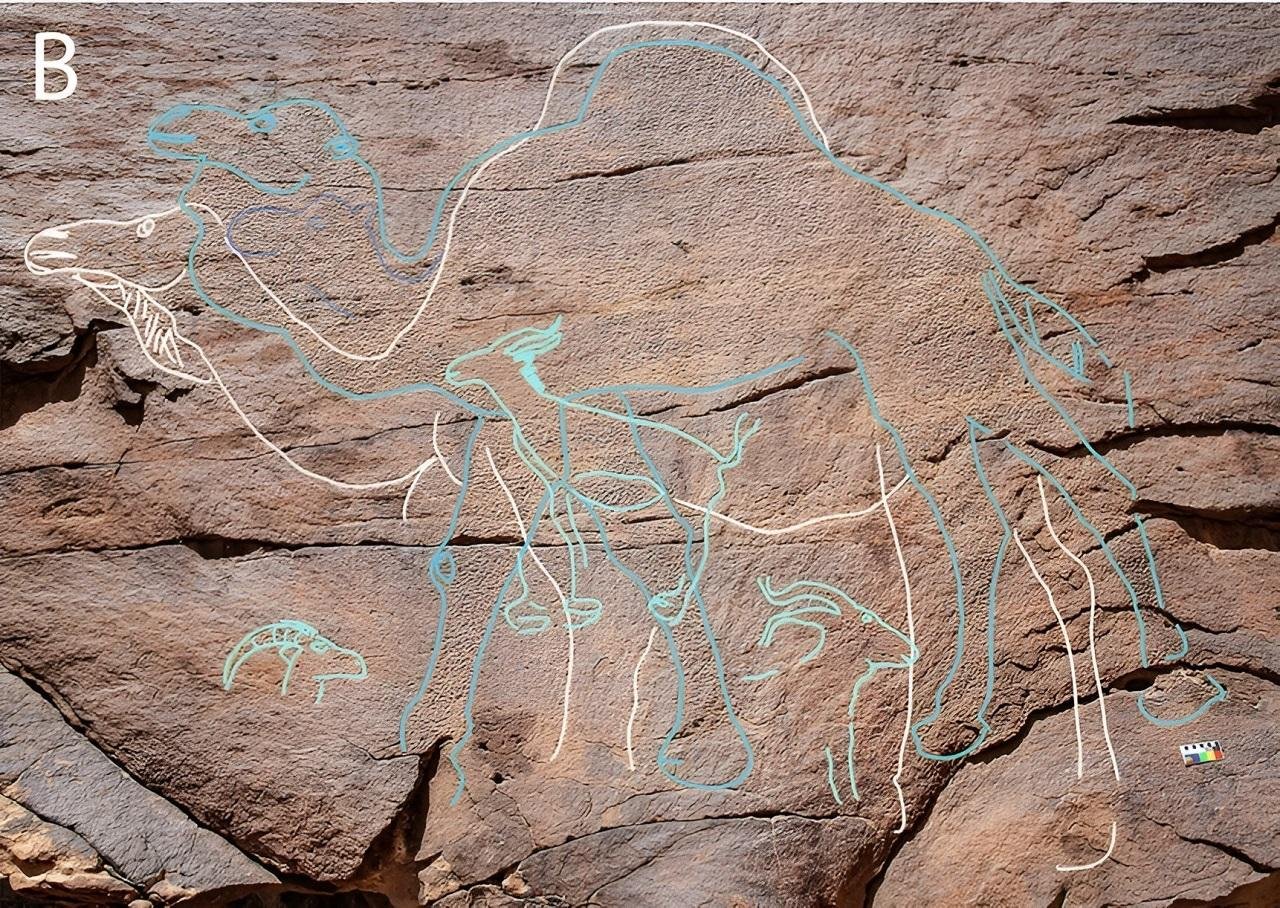

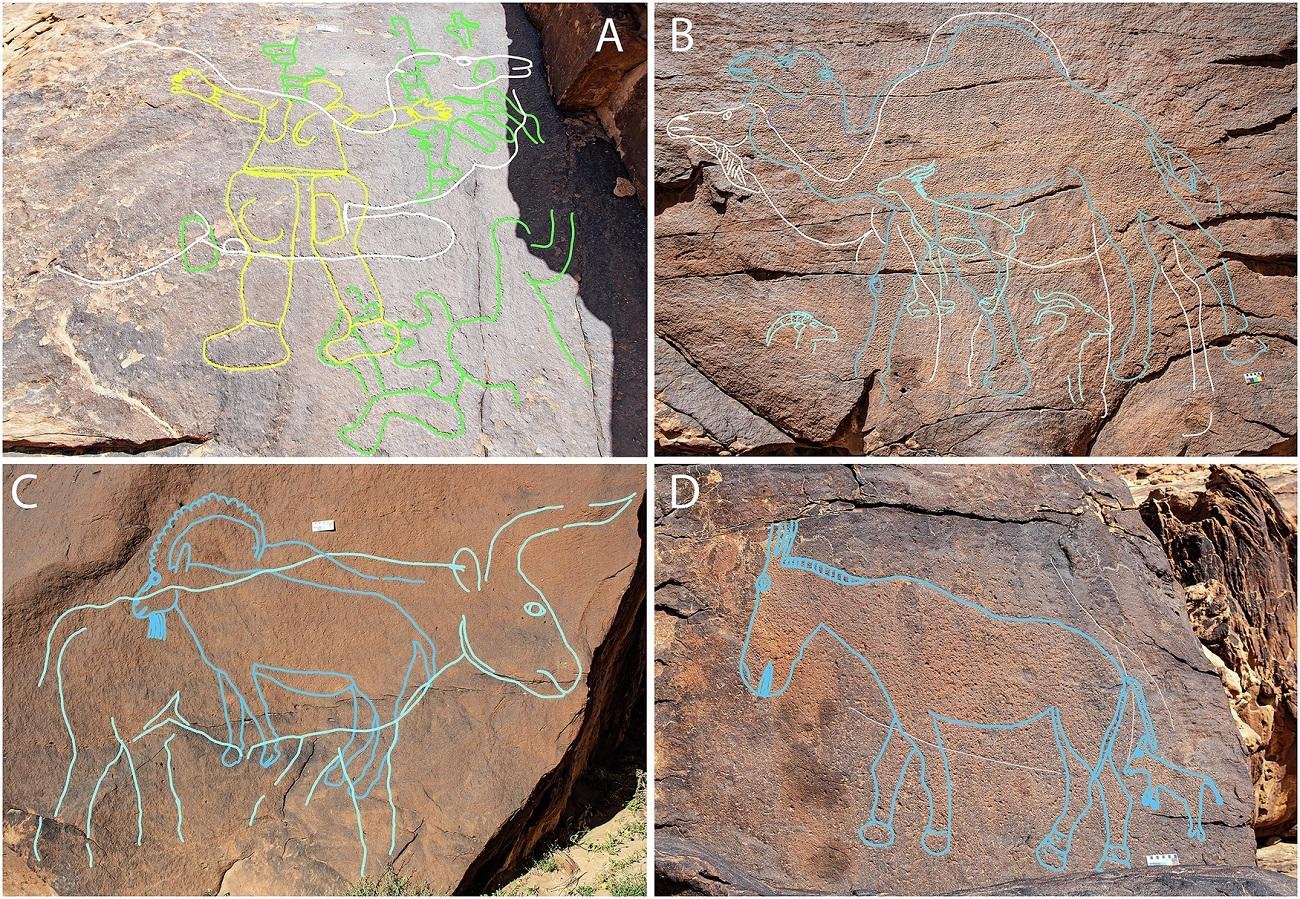

They were found at three sites in the southern Nefud Desert—Jebel Arnaan, Jebel Misma, and Jebel Mleiha—where researchers documented 62 panels with 176 engravings. The majority of the carvings are life-sized animals, predominantly camels, but also ibex, gazelles, equids, and even an aurochs. Individual camels are nearly three meters long, and whole panels stretch over 20 meters across steep cliff faces, rising up to 39 meters above the ground. The creation of such artwork required careful placement of images in places that would be highly visible and also dramatic.

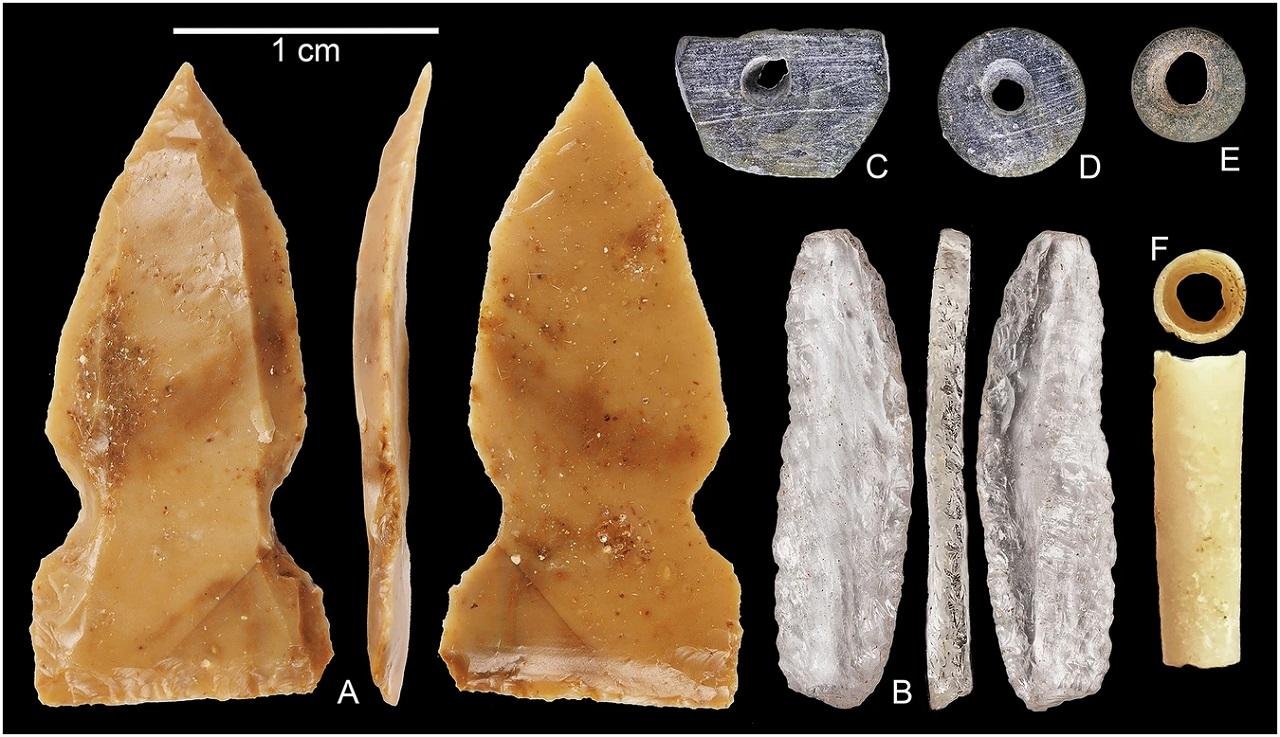

The engravings were created in several phases. Early panels contained stylized human forms, overlain later by more naturalistic representations of animals. Additional schematic figures of animals were added later in some cases. Microscopic analysis, in combination with luminescence and radiocarbon dating, confirmed the engravings’ age. Excavations directly beneath a camel panel at one site produced the stone tool used to create the carving, dated around 12,200 years ago, along with traces of the hearths that provided supporting radiocarbon dates.

Beneath four of the panels, archaeologists exposed more than 1,200 stone artifacts, bone fragments, and ornaments. The tool assemblage was made up of bladelets, scrapers, drills, and finely retouched points. Surprisingly, some of the fragments were identical in form to El Khiam and Helwan point styles found in early Neolithic cultures in the Levant. Alongside these tools were ground-stone beads, a green pigment crayon, and shells from the sea that would have had to be obtained hundreds of kilometers away. These findings show long-distance connections or mobility, linking northern Arabia to coastal or Levantine populations during the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene.

Moreover, sediment analyses in nearby dry basins indicated that seasonal lakes formed in the desert from around 17,000 to 13,000 years ago. These temporary sources of water would have been lifelines for mobile groups traveling through the deserts. The location of the engravings close to gullies and former watercourses implies that the art may have acted as route markers, oasis markers, or territorial boundaries.

Camels dominate the images, accounting for nearly three-quarters of the animal depictions. The majority of them show males in rut, with neck swellings and thick winter coats. Such details imply close observation of seasonal behaviors, which might have been linked to rainfall cycles and the availability of water. The symbolism would have been both practical and culturally important, serving as memory aids and markers of identity in a challenging environment.

Until recently, researchers thought that most of Arabia was uninhabited during the period between the Last Glacial Maximum, about 25,000 to 20,000 years ago, and the onset of the Holocene humid phase about 10,000 years ago. The absence of securely dated sites had reinforced the idea of a “desert vacuum.” The new evidence now shows that human populations not only survived but also created monumental art, maintained long-distance connections, and developed creative responses to the shifting climate.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.