Researchers for generations have tried to understand why Australia’s Ice Age giants — enormous kangaroos, car-sized wombat-like creatures, and massive flightless birds — went extinct. Many have thought that the arrival of humans in Sahul — the ancient landmass that once linked Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea — sometime around 65,000 years ago may have helped drive these creatures to extinction around 40,000 years ago. But new research suggests that one of the most famous pieces of evidence supporting that idea was misinterpreted.

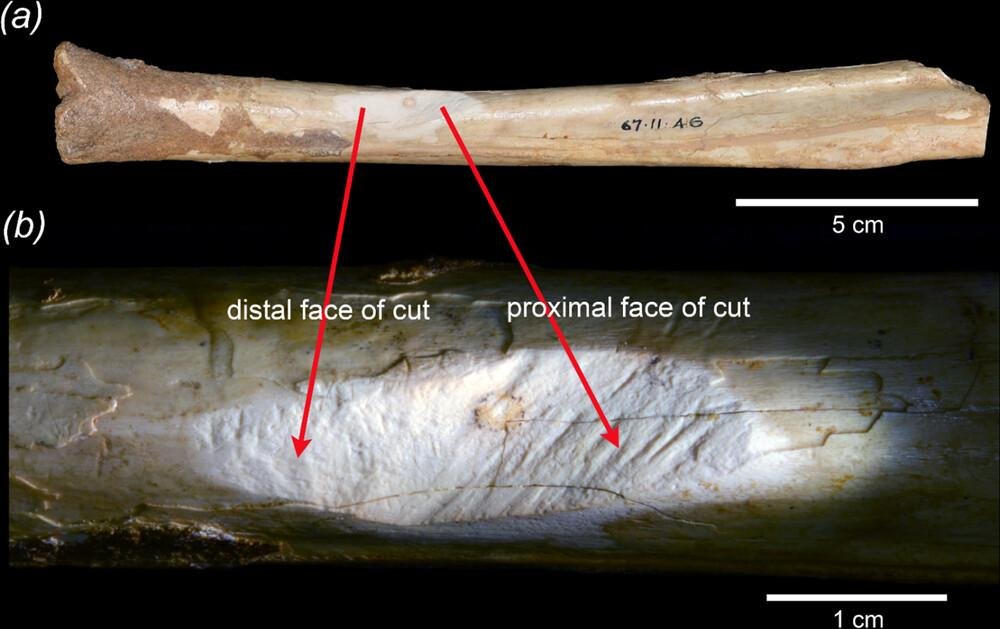

A study in Royal Society Open Science re-examined a 40,000–50,000-year-old fossilized tibia of a giant short-faced kangaroo (Sthenurus) discovered in Mammoth Cave in Margaret River, Western Australia. The bone was originally thought to bear cut marks from stone tools used by humans — evidence, some believed, that early Aboriginal peoples butchered megafauna for food.

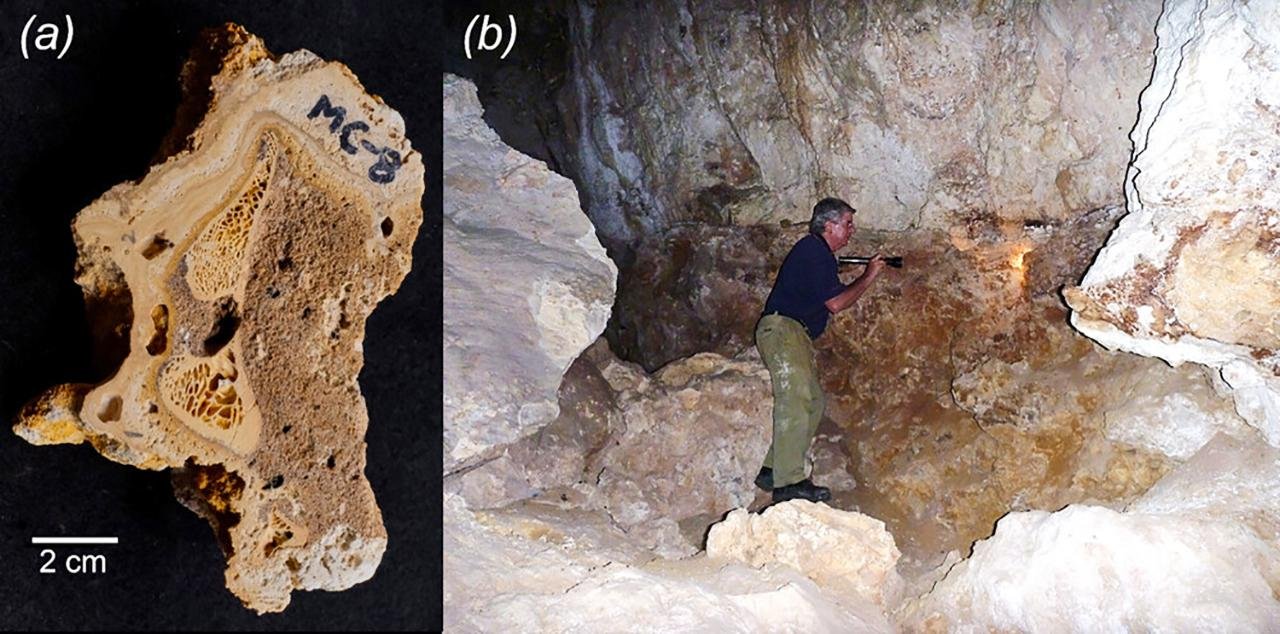

Using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanning and microscopic wear analysis, researchers discovered that the marks had been made long after the animal’s death and likely after the bone had already fossilized. The bone cracks had also dried and aged before being cut. This suggested the marks were not due to butchery but to later human handling — an interpretation-altering finding for the scientists.

The new study suggests that Australia’s native inhabitants were not so much the hunters who wiped out the continent’s giant fauna but perhaps the world’s earliest fossil collectors. Rather than cutting into fresh bones, prehistoric Aboriginal Australians may have gathered and even traded fossils over vast distances millennia before European scientists began studying them.

To test this idea further, researchers analyzed a Zygomaturus trilobus (giant wombat-like marsupial) tooth fashioned into a charm that was obtained in the Kimberley region of northern Western Australia in the 1960s. Using X-ray fluorescence, scientists found that the tooth’s elemental composition was closely comparable to Mammoth Cave fossils, nearly 3,000 kilometers away. This shows that southern Australian fossils may have been transported north through ancient Aboriginal trade systems.

The study also analyzed several other supposed examples of human–megafauna interaction, including bones and eggshells that were once thought to bear evidence of hunting or cooking. None were found to hold solid proof that early Australians killed or butchered these now-extinct animals.

While ancient rock paintings and Aboriginal oral traditions depict giant animals — including the marsupial lion and large reptiles — these records may reflect encounters with fossils rather than living creatures. In fact, researchers propose that Aboriginal Australians might have recognized such fossils as special or powerful, preserving them for cultural or spiritual reasons.

Overturning decades of assumptions, the study challenges established theories about the role of humans in Australia’s Ice Age extinctions. Instead of viewing the continent’s earliest inhabitants solely as hunters, the findings present a more nuanced picture — one of observation, curiosity, and deep-time awareness.

Far from passive bystanders to their environment, Australia’s First Peoples were perhaps the continent’s earliest paleontologists, collecting and valuing fossils tens of thousands of years before modern science existed.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.